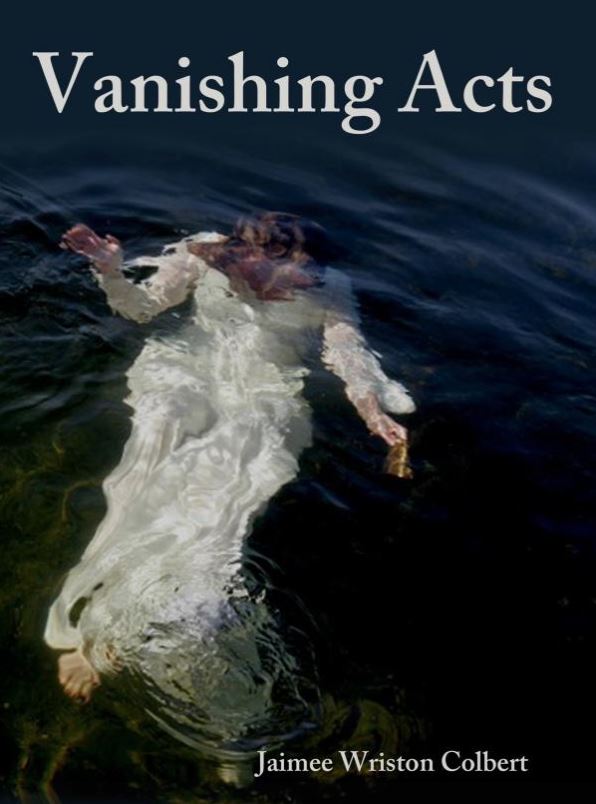

Vanishing Acts

Chapter One – Buddy, 2011

“Chapter One — Buddy, 2011, ” is the first chapter in the latest book from Jaimee Wriston Colbert.

by Jaimee Wriston Colbert

One of Buddy’s earliest memories has to do with death. He’s a little kid about three or four, still those marshmallow legs and he’s running ahead of his mother on the jetty in Rock Harbor, Maine, that noses its way out a mile or so into the harbor, ocean the slick color of a dime all around them, small waves sucking at the sides. He dates his memories this way: PM for pre-move, and AM for after their move out of Maine to Hawai’i, because that’s when everything came apart. It’s like he’s going backwards now. Instead of his life ahead of him the way it’s supposed to be, things to look forward to, he’s slipped from a bright mid-morning back into some dank dawn. AM. After move.

But we digress. That’s a word his mother would use, digress. Gwen likes big words, Jesus, red wine and Xanax, but not always in that order—she likes to mix it up a bit. She also believes there’s a perceivable chance the world will end in September, 2013. She’s talking apocalypse: earthquakes, tsunamis, the dead crawling out of their graves. Most Christian Fundamentalists, new ageists, Mayan calendar enthusiasts and their ilk set their sites on December 21, 2012, but she’s rooting for the following year on the Virgin’s birthday, September 8. It makes sense, she said, that God would pick a special day for such a significant event. She thinks there’s a good chance those right wing Jesus-freaks got it wrong, she told Buddy; she’ll cut them off at the knees.

In the time of Buddy’s memory, the jetty and he and his mom heading toward the lighthouse at its end, she was different. Had a bit more something inside her, less trouble on her face. There they were on this breakwater, she’s strolling along and he’s running out in front of her, silver sea, silver sky too because the fog’s blowing in, and suddenly out of this mist there’s a figure moving toward them, opposite direction. Probably he’s just got on an oversized sweatshirt is all, dark colored hood and it’s pulled up over his head and part of his face to protect him from the damp fog. The thing is they can’t see his face. It’s an empty place under the hood, like a shadow you could put your hand through, come out clean the other side. Buddy stops running and Gwen catches up to him, tugs on his arm, yanks him back beside her. They’re both staring at this hooded, faceless walker coming toward them, his long stride that’s kind of slow, like liquid, like he’s pulling his own legs along through water, no feet, maybe tentacles instead. She hugs Buddy against her, leans down and whispers, “I’ve heard it said, son, if you look Death squarely in the face, what you see is the face of God.”

***

Now Buddy’s legs have grown into the sinewy, stretched-out length of a teenager, and he and his girlfriend Marnie Lo are steaming down the Volcano Highway in her mother’s Plymouth Fury, her slippered foot plastered like a cement block to the accelerator when they hear the shriek of a siren behind them. “Sonofabitch!” mutters Marnie.

He whips his head back, sees the flashing blue lights circle round and round blinking OINK, OINK (he knows a pig when he sees one; his father’s a warden for a maximum security prison). The voice on the megaphone orders them to move over to the side of the road. “Side-a-the-road!” roars the voice. Soft shoulders this road once had, sliding volcanic soil. Pull over and half your car would immediately sink. Like stepping into one of the puka ferns his mom warns him about, long hairy trunks disguising lava tubes shooting down to the middle of the earth.

“Sonofabitch!” Marnie wails for the second time, kind of rolling all the letters into a spit-it-out type of a word. “Let me do the talk, OK? I’m good at this kind of thing.”

What Buddy notices first is the cop’s legs when he gets out of the PIG-mobile and struts over, thighs like meat hooks crammed into his blues. He bends down and peers into Marnie’s window. “You know how fast you were doing?” He glares at Buddy, like Buddy’s the one driving. He’s a haole cop, German maybe, looks like a Nazi. So maybe this won’t go too good for them, Buddy’s thinking, the way this Nazi is staring at Marnie, flat eyes the color of Mel Gibson’s eyes giving her the up, down, then back to her own yellowy-brown eyes, skin the color of a honeybee. Marnie’s half Caucasian, hapa-haole they call it in Hawai’i, the honeybee half is all kinds of things, Hawaiian, Chinese, Filipino. No German to speak of. How he knows the color of Mel Gibson’s eyes is because the night before they watched one of her stepdad’s ancient DVDs, Man Without A Face, sprawled out on the Lo living room’s shag-carpeted floor, her mother’s cats taking up all the furniture. One side of Mel’s face looked like an avalanche rolled over it, but the other side announced he was still Mel Gibson. “Your basic hottie, blue eyes, tan skin, sexy smile and that goddamn adorable butt,” Marnie proclaimed, “the dude is fine.”

“Old,” Buddy said, “the dude is old.”

“So maybe I’m into old guys, huh?” she snapped.

Old guys, all the ways Buddy’s not what she’s looking for. He’s mud-eyed, skin white as bleach, barely a butt to speak of on his jangly, long-ass frame, not old and not much to smile about these days. He stares straight ahead at the Fury’s windshield where a small white moth lights down. The glass is still damp from the rain forest drizzle they just high-tailed out of, little clumpy sparkles like wet salt. “Flew,” the cop whines, “you flew down this highway at eighty miles per! You’re on the Big Island for chrissake, 45 miles per hour, did you think it was NASCAR?” He hooks a slab-sized thumb under his polished belt, then grins into Marnie’s face at his own cleverness exposing vampy canine teeth.

The moth sticks its proboscis into the moisture. Buddy knows about moths and butterflies, the order Lepidoptera. This moth is thirsty for special chemicals, nutrients, salt. He knows another kind of moth that drinks tears from the eyes of cows. It flutters against the cow’s eyes, using its long mouth parts to sweep across the animal’s eyeball making more tears flow, which the moth then drinks. It’s a mutually satisfying relationship, the moth is fed, the cow’s eyes are dried. He appreciates this about nature. Everybody gets something. But the moth’s the clever one. If it wasn’t there in the first place, batting its wings at the cow’s big eyes like some bitchy flirt, the cow wouldn’t be crying. Buddy’s mother said his father was like that. “Had me convinced our survival depended on him,” she said. “What do you know, here we are in Hawai’i without him.”

At sixteen what Buddy likes most is entomology and the idea of having sex with Marnie. Because at that point he still believed it could happen any day, that any moment she’d reach out, those olivey arms, undo his jeans, slide her tender tongue down. What he likes least? That’s easy, his parents and Grandma Madge. Sometimes his mom forgets about Buddy, but she never forgets Grandma Madge. “Grandma wakes up with a howling inside and she thinks it’s hunger,” his mom said, “but I think it’s the person she used to be just falling away.” Buddy’s grandmother has TIAs, what they call shower strokes. Her mind dies a little after each one.

“Well,” Marnie hesitates, sighs, her voice sweet and sticky as a doughnut. She’s peering up into the cop’s looming face, rolling her yellowy-brown eyes. “The thing is we got stuck behind a tour bus at Volcano. You know how that goes.” She yawns and squiggles the top half of her body into a slight, slow stretch, runs her tongue across her lower lip.

The cop shoots up a wormy brow, slides his gaze down and narrows his eyes.

“You’re not toying with me, are you young lady? Because if you are I’d have to give you a ticket, just on the principle of the thing.” He grins and Buddy groans, faking a cough.

Marnie says, “Oh no, I wouldn’t do that. I’m just like, putting out a little something to consider here. See, if I was speeding to make up for having to go so slow before, in a way it evens up, huh?”

Putting out? Buddy’s thinking. That’s retro guy talk for when a girl had sex with you and you didn’t have to buy her food or take her to a movie. Mostly he doesn’t go for guy talk, or even hanging out with guys much. He never felt he was entirely one of them, nor girls neither. Buddy wasn’t sure where he fit—what he wants is to fit with Marnie. That’s why he likes the insect world, they don’t question these things. You do what you’re born to do.

The cop shakes his massive head. “You won’t find logic like that in the laws of the highway, miss. You got any idea how much speeding tickets are up to these days? It’s a lot of babysitting change I’ll tell you.”

The cop’s posture’s gone from rigid to lounging, his chin thrusting its way inside Marnie’s window like it’s independent from the oversized face it’s attached to. Surveying that blackened stubble, Buddy thinks how he must have to shave three times a day. Buddy barely shaves at this point, once a week about does the job. He tugs at his shiny chin and watches Marnie ferret out a purple marker from her purse, scribbling a number onto a gum wrapper. He feels that aching inside, that punished, helpless hurt. The moth finally wheels away in a gust of wind, and Buddy misses it like a lost friend.

“We’re on our way to the airport,” Marnie informs the cop who could double as a steroids poster-boy and who looks only at her now, Buddy might as well be in another time zone. “And FYI I’m no babysitter. Like, do I look the type to hang out with some bratty little kid? I’m a model. I got a gig in Honolulu.”

“Well Miz Model,” the cop straightens, stretching his stuff, “I know what it’s like trying to catch a plane, wouldn’t want to blow your gig. So today I’m calling this a warning.” He finishes writing something on his note pad, tears it out with a flourish and hands it to Marnie. “But you better watch that speed, because next time I’ll give you that ticket.” He winks at her then struts on back to his cruiser, slips inside and peels off. Marnie rearranges her tank top that she’d tugged down when the cop first appeared, displaying more than just a shadow of cleavage. “What a major creep!” she says.

Buddy memorizes that cleavage. Takes a mental snap shot to drag out during his sleepless nights with his other imagined photos of her body parts, slipping them together like a jigsaw puzzle. “So why’d you give him your phone number then? You like told him your life story practically. And BTW, letting a pig peek down your shirt to get out of a ticket is pretty cliché, don’t you think?” He has to be careful. When Marnie gets mad she snubs him for days. She’s on his mind all the time, an itch under his skin, a popping, burning inside.

Marnie rolls her eyes, aims the Fury back onto the highway and in minutes they’re flying again, past ginger groves, fern forests, skinny waving papaya trees, palm trees, small houses with corrugated roofs and lava gardens, then further down the mountain toward the sea gleaming like a sheet of stretched out aluminum. Six months ago when Buddy’s mother hauled them from Maine to Hawai’i, she pointed from the plane at snow-capped Mauna Kea and announced, “They can ski that mountain in bathing suits.” As if that would mean anything to Buddy. As if his life without his father in it could be a life. He thinks about his dad, picturing the way he looked the last time Buddy saw him. He memorized what his dad wore when he drove them to Portland Jetport, silence thick as the fog hanging over the road like smoke. His dad was wearing his red flannel weekend jacket, the one he wore every weekend, the one that drove his mom crazy. “Sign of an unimaginative person,” she said, “a creature of habit.” His dad once put that jacket around Buddy’s shoulders at a Patriots game, a light rain blowing in sheets across the bleachers and he’s shivering beside Buddy in his t-shirt. It’s the only game they ever went to, and Buddy didn’t understand why they kept sitting in that cold rain; did it feel to his dad like something that had to be finished? His dad didn’t care about the Patriots, neither did Buddy. The flannel was still warm from his father’s shoulders.

So why couldn’t his parents just live together like roommates, they wouldn’t have to even share a bed. “Good-bye Richard,” his father said. Buddy’s real name’s Richard but nobody calls him that. Hitter Harrison, third grade Little League pitcher nicknamed him Bucky on account of his big teeth, and the name stuck for a while, then eventually became Buddy the way nicknames do, migrating from one form to the other, no remembered connection between the two. Bucky, Buddy, he doesn’t mind. Richard would sound moronic in Hawai’i where guys have names like Poi-dog, Barracuda and B.B. (for Big Brah); it would set him apart even more.

His mother wanted to put braces on them but his father said wait. His father’s the warden for Rock Harbor Adult Correctional and his motto is, Wait And Be Ready. He once told Buddy, “Never question what you think you know. If you question things you lose the advantage of being right.” So they yelled at each other, his mom and his dad, about his teeth, about how his dad always waited on things and thought he was right. Their house in Maine became a cold house, like it was always winter.

Buddy misses that house, an old house in a neighborhood of old Rock Harbor houses, big yards, trees that blossomed every spring. He misses the sense of permanence of his life in Maine, even though he knows now it was all a lie. “Our house is on the market,” his mother announced a few weeks after their exodus, her lips pinched tense as guitar strings.

“Bud-o, what you don’t know about life,” Marnie says now. “Hell-o? You hear me tell that loser I’m going to get with him? Like, did you actually think I’d give some cop my cell phone number? He was so busy mouthing off about the laws of the highway and eyeballing my tits he didn’t think to look at the number on my license. Even if he did he’d call my house and get a date with The Sleaze!” Marnie tosses back her lava colored hair and roars.

Buddy laughs too. The ringing in his ears morphs into a mantra, tits, tits, tits! When he thinks about Marnie’s breasts it makes him buzz all over, like he’s plugged in, like he’s electric, like he could turn on and shine. He doesn’t like the word tits as much, too bovine. Breasts, a good word. Marnie calls her stepfather The Sleaze. None of them live with their real parents, at least not both at the same time, not Marnie, not Buddy, not the others they hang with sometimes. Marnie says if people were meant to have mothers and fathers men would also get pregnant. “You can tell God’s a man,” she says, “because if he was a she guys would get periods.”

Buddy slides his hand over the distance of seat between them, over the torn fake leather upholstery, up and under her arm hanging loosely on the steering wheel. “Guess I’m just a jealous kind of guy,” he says in a husky voice, trying to imitate some actor they watched together on some cable station movie. Tentatively, heart hammering, he slips his hand up under her top. Marnie has been letting him do that; she ignores him when he does, like he’s not really doing it at all. A thrill shoots through him, a hot, pounding, jumping sensation like his blood’s on fire, like he’s burning up inside.

He closes his eyes, rubs her hard little nipple between his thumb and forefinger like a marble. Nipple, another highly agreeable word. The Fury cruises down the Volcano Highway, air like a steam bath leeching in through the windows, its verdant, mossy smell. Buddy inhales, stifles a yawn. Marnie squirms and Buddy reluctantly pulls his hand back, eyes still closed. The motion of the car under him is like the spinning of the world, too fast to jump out, too late to turn back. Never mind that he stole money from Grandma Madge’s room so he and Marnie could fly to Honolulu. His grandmother won’t know the difference. Never mind that his father sends money in the prison’s blue envelopes so he can go to a private school he hates, not even a ‘How are you!’ scrawled inside for Buddy.

Was it Buddy’s fault his parents couldn’t stand each other? His giant teeth? Migraine headaches that slammed down the brakes on ordinary life for the three of them? “You always manage to grow a headache at exactly the worst times,” his father complained, as if his headaches were toadstools, persistent and useless in their front yard, something to wipe out with the lawn mower, the weed whacker. Tried to convince himself he couldn’t care less. Marnie said parents are basically useless. She said her own father beat-feet out of their life almost as soon as her mother could stand after squeezing her out. Then her mother screwed around for a few years, Marnie said, a major ho. One night she brought home The Sleaze. He was in her mother’s bed the next morning and the morning after that, weeks, months, going on years now. “Guess she screwed him into something permanent, “ said Marnie, “like a socket maybe. Because then she goes and marries the dude.”

Hilo Junior Academy is for retards, far as Buddy can tell, a school for “exceptional learning styles.” He’s there because he has a sort of brain chemicals imbalance that causes migraines so bad he fantasizes taking a knife, cutting them out. Brain chemical screw-ups are rampant in the Canada-Johnstone-Winter clan, we’ve got the mood-disordered depressives, the nut-job demented, delusional alcoholics, and then there’s Buddy. Family tree. He was absent from school as much as he was there. Well what difference did it make, wasn’t he numbed into a state of brain-dead whenever he went? The neurologist his mom sent him to said Buddy needed a change in “attitude,” that he was too tense, a powder keg. Only instead of firing off a couple rounds in a school assembly he blew up in his own head.

HJA is where Buddy met Marnie Lo, in his culinary arts class. He’d noticed her around campus, who wouldn’t? Mane to her waist, most of the time black though sometimes she dyed it different colors, purple daze, Halloween orange, always her tight black clothes. He started dressing in black too for a while, and according to his mom, their cousin Kiki called it a death thing on account of the breakup between his parents.

D.J., Buddy’s food prep partner whispered, “That chica’s got anger issues, hold on to your balls!” The teacher was barking out a recipe for luau chicken, and Marnie hacked away at the raw carcass on the high silver countertop like she was murdering it, like she had some major grudge against it; vicious swings of the knife, as if the poor bird wasn’t already weeks dead and previously frozen, flesh, bone, all of it confetti under the glint of her silver blade.

“What you staring at haole boy?” she asked Buddy. “You never seen someone cut up chicken before?” She tossed the microscopic remains into a bowl of coconut milk, grinning.

He shrugged, face pink. “You have some bones in it.”

“Got a problem with that? Bone’s good for you, calcium you know. Like it keeps the body hard.” She winked and her eyes traveled the length of him the way guys check out girls. “Don’t your mommy ever cook chicken for you?”

“My m…m…mother (since his parents separation Buddy had developed this unfortunate habit of stammering sometimes when he talked about them), my mother can’t cook pork and beans.” Yikes! You get the picture? There he was babbling like some moron to the most babelicious girl in the school, maybe the whole state, about beans! He blushed violently, skin the color of those bloody chicken scraps quivering like Jell-O under her knife.

“Pork? You called it pahk. What kind of talk is that? Where you from, anyway?”

He told Marnie about Maine at lunch that day, the two of them lounging on prickly crab grass under a banyan tree, its exposed airborne roots scraggling down around them like an old man’s beard, sharing a plate of fried teriyaki tofu from the cafeteria.

“So you’re a coast haole from the east coast? I never met somebody from the east coast.”

“My m-m-mother’s from here. She grew up in Hawai’i. Her grandmother was Hawaiian so that makes her part Hawaiian and me too a little, if you do the math.”

Marnie shook her head, leaning so close to him that a hank of her black hair grazed his arm. He felt a chill like a cold wind breeze up his spine. “Thing is, Buddy Winter, I effing hate math. My subject’s recess. Anyway, if you’re not born here it doesn’t count. It’s like you’re renting Hawai’i.”

“They think like that in Maine too. You’re not a Mainer unless you’re born into it and live your whole life there. The way some talk it’s like they evolved from amoebas into their own living rooms.”

Marnie grinned, her mouth so close Buddy could smell the tang of teriyaki on her breath. “Well damn, haole boy, I guess that means you don’t belong nowhere, huh?”

Buddy swipes angrily at the sudden tears in his eyes, thinking about the truth of this now, how he really doesn’t belong anywhere. Humid air pours into the car windows as the Fury burns to a stop at the first traffic light they’ve seen for miles. “Hilo-town,” Marnie announces. Buddy nods, then shoots his arm up and over the seat, around her tight little shoulders, hoping she won’t notice the wet on his cheeks. There are moths that drink mud, blood, anything. He imagines sinking his mouthparts into that sweaty place on Marnie’s neck where her fine hairs wisp like curls of smoke. He’d attach himself there and never let go.

After abandoning the Plymouth along the side of the orchid and lava-lined road leading into Hilo Airport they’re standing at the Aloha Airlines desk, trade winds whipping through the wide open terminal, stirring up a mean scent of flowers from the nearby lei stands. The wind messes with Marnie’s hair, and when she lifts her arms to pull it back her top slides up, revealing a golden slice of belly flat as the TSA information card she’s waving in Buddy’s face. “Hey!” she tugs at the sleeve of his t-shirt that says Maine Lobster Fest, pretty dorky but he’s a kid at this juncture. Clothes are bought for him. “Like I need the bills for the tickets.”

He shoves his paw reluctantly into the pocket of his jeans emerging with the fistful of twenties he scrounged from his grandmother’s room, handing them to the ticket agent. Buddy feels a wave of nausea. How low can he go? He found some under her bed, and he doesn’t mean the mattress, lying loose on the floor. He discovered a couple fifties (Marnie doesn’t know about these) stuffed inside a pair of glittery stiletto shoes wasting away at the back of her closet. “Grandma was a world-class beauty and quite the dancer,” his mom told him. These days she wears pink canvas athletic shoes, some cheesy bargain brand. The tens were in a dusty fish bowl filled with pencils, sea shells, poker chips, clots of cotton balls stuck together every which way like molecular models, half used lipsticks the color of dried-up roses, twisted scraps of tissue and ancient ticket stubs. Concerts, cool ones too like The Dead, when Garcia was alive. Her mind dies a little each day, Buddy reminded himself as he pocketed her money.

“I’ll most likely get paid this time for modeling,” Marnie says. They’re lined up between two ropes like a herd of cattle, waiting to be loaded onto the plane.

“Will it cover the cost of these tickets? I’m just wondering because, you know, it’s my grandmother’s money.” He avoids her yellowy-brown stare. Careful, he thinks, it won’t work having Marnie mad at him in Honolulu. A big city where being alone could get pretty ugly.

The line’s finally moving and Marnie clutches Buddy’s hand like he’s her little kid, lugging him along behind her as they troop out onto the tar-smelling tarmac then up the 737’s steel steps. He doesn’t mind. The way everyone stares because she’s so hot, they can’t help but notice she’s chosen him. “So what!” Marnie shouts over the roar of the engines. “Your grandma’s pupule, yeah? Crazy people don’t need money, they can entertain themselves.”

Flying out of Hilo Airport the plane circles above Mauna Kea. Six months ago there had been that snow, skiers darting about like beetles below. The wings of the jumbo-jet made a shadow like a pterodactyl on the glaring whiteness, and staring out the window at the strange land he’d felt dead inside, pulled apart, an insect without its wings. “It’s the best thing, Buddy,” his mother had said for the tenth time that day. “Grandma needs us. Kiki called me. Your mother’s having trouble living on her own, she said.”

“Give me a break! This is about you and Dad,” he snapped.

“Yes, OK, in part, but I’m her daughter, dammit. I’m all she’s got.”

He had turned toward his mother then, his glassy stare. “So what do you want me to say? Should I swear too, goddammit? I thought you God-freaks weren’t supposed to swear. It’s against some law isn’t it?”

“At the moment I don’t give a damn. Just don’t shut me out. Besides, as long as you don’t put God in front of damnit it’s not swearing. Look, I haven’t been the world’s worst mother, have I? I didn’t beat you, lock you in a closet, starve you. Don’t I pretty much give you what you need? Talk to me.”

He made that strangled sound like he was choking down a too-big bite of meat, mumbling yeah right under his breath. “Fine. My topic is butterflies. Butterflies have four stages in their life cycle. This allows them to adapt to a wide range of climates, even climates like the tundra or the arctic. They can live in severe cold, in a resting state known as diapause. They don’t need to respond to outer stimuli, because inside they’re quietly surviving.” Then he pulled away from her, closing his eyes until the plane touched down. “Aloha and welcome to Hawai’i!” a flight attendant announced. Maine, his history, erased.

Now it’s June and the volcanic ridges and craters stick out like pockmarks on the craggy face of Mauna Kea. Buddy feels alternating waves of guilt and exhilaration. He stole money from his grandmother, and his mom thinks he’s spending the night with a kid from his English class. But he’s free. He’s in charge. He could start a new life with his girlfriend. She’d let him feel her breasts and then the rest of her. Maybe they’d even be in love.

Buddy lifts a urine-cup sized specimen of guava juice off the flight attendant’s tray and hands it to Marnie, who’s pawing through a magazine, then take ones for himself. He yawns, rubs his eyes. He hasn’t been sleeping well. Keeps having the same weird dream that began in Rock Harbor right before they moved, and he’s been dreaming it in its various incarnations since. Last night’s version, he’s walking along the rim of Halema’uma’u crater and he notices a body lying on the lava-strewn side. An awesome body, naked as rock, skin the color of vanilla ice cream against the black lava, curled up like a S. Her hand was reaching out.

The dream pretty much unfolded that way each time he dreamt it, a woman’s body, dead. Buddy didn’t have a lot of experience with death then. His dog had died and that sucked. His grandmother was dying he supposed, though his mother shook her head when he asked. “Of course not! They’re just baby strokes.”

He settles back against the seat, steady thrum of the plane’s engines like some rap song, just enough rhythm you ignore the words. Marnie sticks her iPod’s earbuds in her ears, chomps down on a wad of grape bubble gum, scrutinizing an ad for the “creamiest” coconut shampoo in Aloha magazine. Buddy runs a hand through his own dark tangle of curls framing his sallow face; like a halo his mom used to say, sliding her cool fingers through his hair. Closes his eyes. For a runaway he doesn’t feel too bad.

About the author:

Jaimee Wriston Colbert is the author of six books of fiction: Vanishing Acts, her new novel; Wild Things, linked stories, winner of the  CNY 2017 Book Award in Fiction, finalist for the AmericanBookFest Best Books of 2017, and longlisted for the Chautauqua Prize; the novel Shark Girls, finalist for the USABookNews Best Books of 2010 and ForeWord Magazine Book of the Year; Dream Lives of Butterflies, winner of the IPPY Gold Medal Award for story collections; Climbing the God Tree, winner of the Willa Cather Fiction Prize, and Sex, Salvation, and the Automobile, winner of the Zephyr Prize. Her work has appeared in numerous journals, including The Gettysburg Review, New Letters, and Prairie Schooner, and broadcast on “Selected Shorts.” She was the 2012 recipient of the Ian MacMillan Fiction Prize for “Things Blow Up,” a story in Wild Things. Other stories won the Jane’s Stories Award and the Isotope Editor’s Fiction Prize. She is Professor of Creative Writing at SUNY, Binghamton University.

CNY 2017 Book Award in Fiction, finalist for the AmericanBookFest Best Books of 2017, and longlisted for the Chautauqua Prize; the novel Shark Girls, finalist for the USABookNews Best Books of 2010 and ForeWord Magazine Book of the Year; Dream Lives of Butterflies, winner of the IPPY Gold Medal Award for story collections; Climbing the God Tree, winner of the Willa Cather Fiction Prize, and Sex, Salvation, and the Automobile, winner of the Zephyr Prize. Her work has appeared in numerous journals, including The Gettysburg Review, New Letters, and Prairie Schooner, and broadcast on “Selected Shorts.” She was the 2012 recipient of the Ian MacMillan Fiction Prize for “Things Blow Up,” a story in Wild Things. Other stories won the Jane’s Stories Award and the Isotope Editor’s Fiction Prize. She is Professor of Creative Writing at SUNY, Binghamton University.

Fomite Publishing

58 Peru Street

Burlington, Vermont 05401

Cover image by Maile Colbert

www.mailecolbert.com

ISBN-13: 978-1 944388-25-6

Price: $15.95

Amazon

Recent Comments