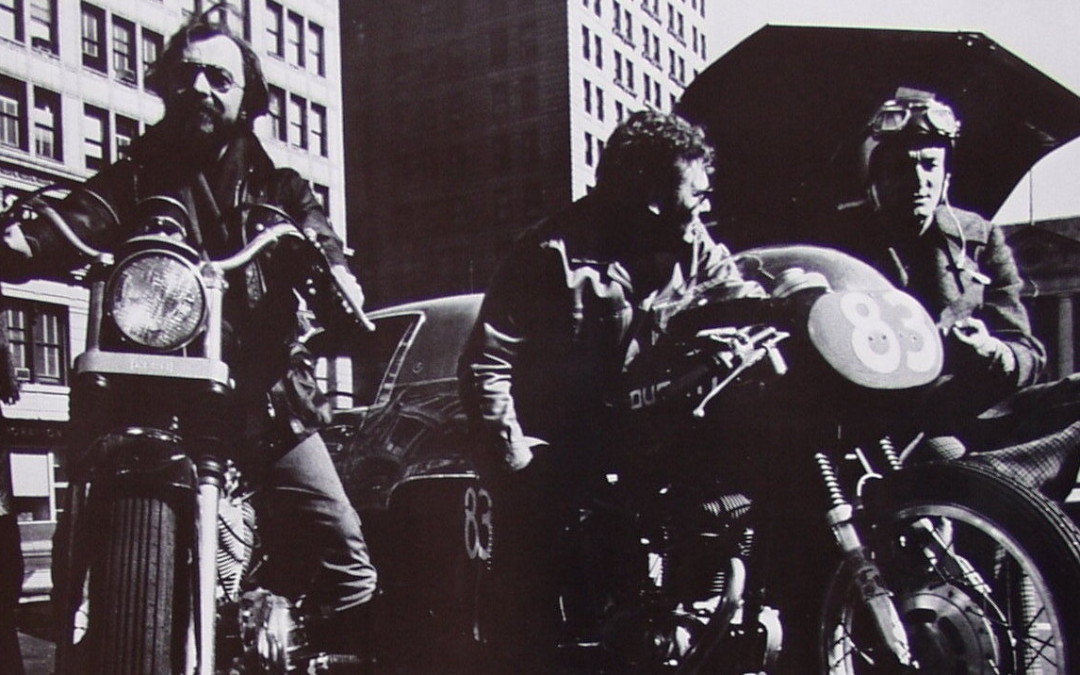

Peter Moore Photo

The author, Poleskie (left), with Larry Zox and Larry Rivers on Union Square, NYC, 1968.

Motorcycle Memories

By Stephen Poleskie

The historically cold winter has finally left us. As it’s warmer now, we have the windows open; no air conditioning for our 150-year-old farmhouse. One thing my wife and I dislike about Florida is the need to have one’s air-conditioner cranked up all year long. Living on the side of a hill and having twenty acres of woods and fields, surrounded by a 700 acre state park, we enjoy having the windows up to let in a fresh breeze. Unfortunately, the open windows also let in the noise. As the road out front is quite steep, passing vehicles are often running at full-bore, despite the 25 MPH speed limit sign. However, the record as I know it is held by a vehicle going down. On one of those rare occasions when the town installed a flashing speed limit indicator across from our house I actually saw a motorcycle go past at 83 MPH.

The morning is typically announced by the loud mufflers of the grease-balls in their pickup trucks. Next comes the howl of the school buses. Why school buses should be so loud is something that has never been understood by me. And then, if the weather is half good, there are the motorcycles. Coming up the hill it’s a roar or a whine, depending on whether the bike is a Harley hog or a café racer. Going down it’s a muffled growl and a pop, pop, pop, or a whining ring, ding, ding, as the rider downshifts. But I can’t complain about the motorcycle riders, as I was once one of them myself. I can recall fondly rattling down the canyons of Manhattan with my straight pipes blaring. If you are not familiar with the term “straight pipes,” it refers to an exhaust system that functions without the encumbrance of a muffler. This is supposed to improve the efficiency of the engine and make the bike go faster. The actual amount of improvement is debatable, with many observers suggesting that the increase is actually psychological. Loud noise implies big cojones.

My motorcycle riding days all started with my mother winning a raffle at her church; or at least she thought she had. A 50cc Honda was the first prize. Talking to me on the telephone she told me about her good fortune and asked me if I would like to have the Honda, since neither she nor my father had any intention of riding the machine. As I was living in Lower Manhattan at the time I thought that this would be the perfect transportation for me. Thus, I was very disappointed when I phoned the next week (I always called on Sunday), and learned my mother had not won the Honda, but the second prize, which was a hand-made quilt. In the meantime, I had become so enamored with the idea of owning a motorcycle that there was nothing I could do but take myself off to Bronx Honda on Bruckner Boulevard in the Bronx and buy one.

Little did I realize that I was beginning the equivalent of a drug habit; once you’re hooked by motorcycles you keep wanting a bigger fix. My new Honda 50cc soon lost its appeal. It was too small, and it didn’t go fast enough. It had no panache, even though I had taken off the muffler to make more noise. I needed to upgrade, but, at the time, my budget was limited. Fortunately, I sold a small painting, so I bought a Honda 160. It was a medium-size bike that to the casual observer could almost pass for a big bike. And it looked like a motorcycle, unlike my 50cc Honda, which had a step-through frame, so gave the appearance of a motor scooter with motorcycle-size wheels. Alas, the attraction of my 160 soon faded.

Honda had just unveiled a new model, the Honda 450. It was called the 450 even though it actually had only 444cc. In a number of ways this bike was quite revolutionary. I cannot recall all of the things that made it different, but I do remember it was the largest motorcycle the Japanese had built up until that time. The 450 featured some advanced engineering that included two downdraft carburetors of unique design. Honda’s new design features enabled the stop light drag racer riding a 450 to blow off the popular English-made bikes featuring 650 and 750ccs.

I took a Honda 450 for a test ride and knew that I had to have one. Although I had owned my 160 for only a few months, I traded it in. Now I could ride with the big boys, well not the really big boys, the outlaws who rode Harley-Davidsons, but the riders who gathered on West Eight Street in the Village, or go cruising around Lower Manhattan with my friend Larry Rivers.

Although there were not yet that many Honda 450s on the road, or in America for that matter, I decided I needed to customize mine. Perhaps it was my artistic temperament. Everything I ever owned I ended up modifying and painting so that it was different from everyone else’s. Or perhaps it was only my youth, a desire to find my own place. I remember not being able to understand when I learned the owner of Ferrari Motor Cars preferred to drive around in a Fiat 500. He was an older man. Now that I am an older man I am content to drive around in an eight-year-old Dodge of the lowest price model. In college I was embarrassed that my powder blue Plymouth convertible was three years old.

Thus, I customized my Honda 450. The gas tank had chrome panels on the sides, so I stripped them off. And the fenders, which were only painted, I changed, first “bobbing” the rear one, and then sending them off to be chrome plated. Now there doesn’t seem to be much logic to removing chrome where it exists and plating surfaces that were previously painted, but at the time my Honda drew admirers whenever it was parked. I also replaced the stock handle bars with a flat bar, that gave the machine a racy look, and required the driver to ride in a bent forward position. The mufflers were also removed and replaced with “trumpets.” These were devices that looked like mufflers, but had nothing inside. Their shape caused the exhaust note to actually sound louder than straight pipes.

I still can’t imagine how I managed to do all that I did back then in New York in the late 1960s. I ran my screen-printing shop, painted paintings, and had an active social life, which included museum and gallery openings and “making the scene” at Max’s Kansas City.

It was inevitable that I would become involved in racing motorcycles. I was quite successful drag racing with the Honda 450 at New York National Speedway in Center Moriches out on Long Island. I won my class every time that I ran, and usually also won “Bike Eliminator.” However, after a summer of racing in a straight line, I grew tired of this activity. For the next summer I decided I would try road racing, and bought myself a Bultaco TSS. This was a genuine factory racer that in the previous two seasons had raced on the Grand Prix circuits in Europe and the USA.

I must confess that I am also reminded of my motorcycle days in the winter. During those colder moths it is the aches in the bones I have broken from the falls I have had. This is not because I was a bad rider, but a hard rider. There is that bit of gravel or oil that might bite you when you have your machine leaned over and are taking a curve a bit too fast. Or the wheel that comes off your dirt bike while navigating a mountain trail because you hadn’t checked the tightness of the bolt that holds it on. Or being run off the track in Virginia by another racer for something I said to his wife in a bar the night before.

I had the misfortune of running into what I thought was an open field, but actually had a ditch in the center. Hitting this at 90 MPH sheared off the front forks of my Bultaco, causing me to slam my body into the gas tank and then pitch over the handlebars. I broke my right arm, my left and right wrist, my left leg, and fractured my vertebrate. I was in the hospital for a month and spent another month rehabilitating. I went to George Plimpton’s annual party at The Village Gate on crutches with my arm in a sling. Reminding George about the book he had written about playing football with the NFL Detroit Lions, I asked him if he would like to write a book about motorcycle racing. Looking me up and down, George smiled: “No thank you. . . .”

This is a great story showing the addictive allure of motorcycles and their world. The ending is humorous