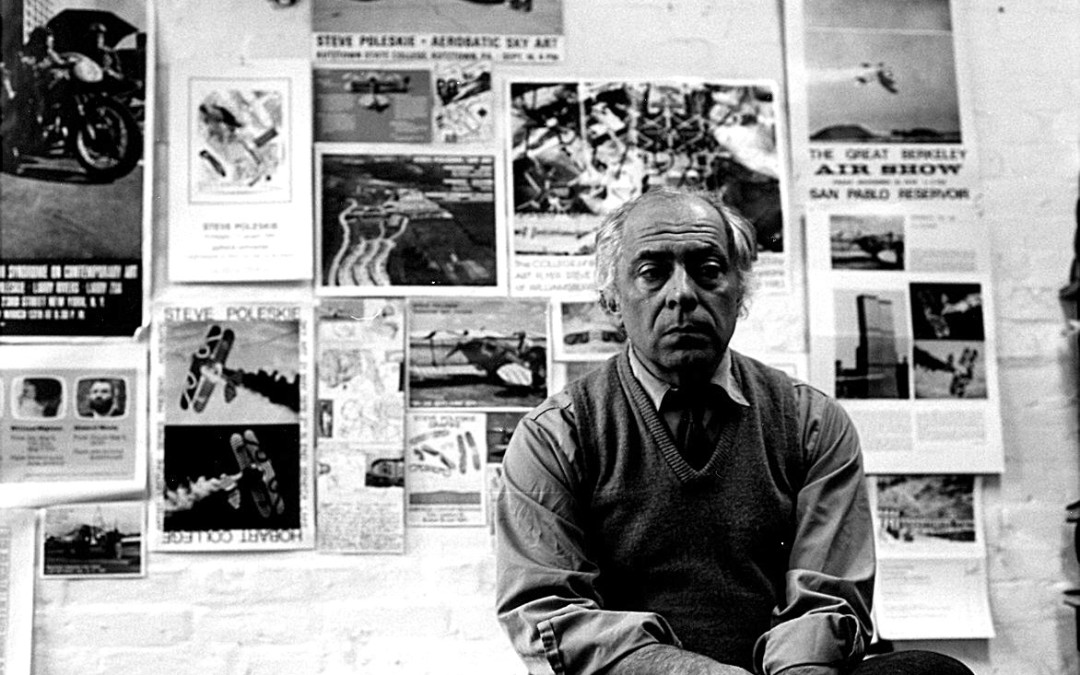

photographer unknown

The author wearing one of the “magic shirts” in his Cornell studio, ca 1992

*

*

CHAIN MAN’S FREE STORE

by Stephen Poleskie

The shirt I am wearing while writing this piece is over forty-five years old. It is still in perfect condition, having no rips or worn spots; it even continues to hold its permanent press. No, it has not been in a drawer for the past forty-five years; in fact I wore it almost daily when I was teaching. It is one of two I got back then at Chain Man’s Free Store.

I was new to the college, having been recently invited there to teach in the art department. I wasn’t sure if I planned to stay. I expected that I would just do a few years and then go back to The Big Apple, as Manhattan had come to be called in the Sixties. But a substantial paycheck every two weeks has a way of changing one’s life. That, however, is the subject for a different story. One fact you may know, if you have read my previous columns, is it was in Ithaca that I got hooked on flying airplanes, an addiction that can be as expensive as hard drugs, especially if you’ve bought five of them. Mercifully, I never owned more than three at any one time. My flying experiences did change my art, but that too is another story.

Back in 1968 performance art was still in its infancy. I hadn’t expected to find any practitioners of this new genre in the rather conservative academic institution I was teaching at; but there was Chain Man. He was a graduate student who walked around with a thick, steel chain wrapped tightly around his neck, which supposedly had been forged in place so that he could never take it off. He had a long explanation for the significance of this adornment, which he was happy to relate to anyone showing the slightest interest. Rumor was Chain Man had several spiels that he varied to fit the concerns of his listeners. These stories drifted wildly around Capitalism, Communism, and the controversy over the war raging in Viet Nam. And then one morning, I came into class to find my students only too eager to relate the latest art department gossip: “Have you heard? Chain Man is a fake.”

“What do you mean?’ I asked, trying to sound interested.

“His chain has a trick link,” a student informed me. “He doesn’t wear it all the time; he takes it off at night when he goes to sleep.” Thus Chain Man lost his credibility.

He must have hidden out sulking for several days as no one reported seeing him around campus. When Chain Man did reappear, he was not only wearing his chain, but also had a huge bandage on the left side of his neck. On top of the bandage was a chain link sporting a rather crude weld. The story was that Chain Man had engaged a freshman sculpture student to give permanency to his chain. Little did either one of them realize that the thin strip of asbestos, which they slipped beneath the chain, while preventing a fire, would not reduce the great heat generated by the oxyacetylene welding process. And so, Chain Man not only had a permanent chain, but also a permanent scar on his neck. No one was sure how the chain would be removed, if ever, without doing more damage to Chain Man’s epidermis.

The semester wore on. Having lived in Lower Manhattan for the previous six years I had forgotten what snow looked like on tree limbs. I was taken by surprise with winter’s early arrival here in upstate New York. The tedium and petty intrigues that are the substance of academia persisted. I wondered why any serious art student would have come to this place, not that we had that many of what I would consider “serious students.” I couldn’t imagine any art student wanting to belong to a fraternity or sorority, but from the conversations I overheard during breaks most of them did.

After several false starts, spring finally came, and along with it the ritual of student final exhibitions. For second year graduate students the word “final” had an ominous ring. Most of them were going out into the world unsure of what their next situation would be. Few MFA graduates ever found the college teaching job that they thought they were preparing themselves for. Many of them would go back to where they came from, and probably do what they had been doing before, thousands of dollars poorer, and undoubtedly deep in debt, not much smarter than when they had arrived at our celebrated institution. Unfortunately, some students even left having had whatever fresh ideas that they arrived with driven out of them by the ultra-conservative members of our faculty.

But Chain Man was determined not to be beaten. The word around the department was that his final show, the content of which was being kept a deep secret even from his committee, would, to quote Chain Man: “Knock ‘em dead.”

And so the big day arrived. As I headed down the hall to the gallery for the opening of Chain Man’s show, I was met by students coming the other way, laughing and joking and carrying arms full of stuff: clothes, books, art supplies, a stereo player. I walked into the gallery to find Chain Man sitting naked on a chair, while all around him his fellow art students rummaged through his possessions. A large, hand-lettered sign hanging above the rapidly dwindling piles of things lining the walls read: Chain Man’s Free Store. This is all I have; so take what you want!

“Hello, Professor,” Chain Man said, making eye contact while, I suppose in deference to my rank, covering his private parts with his hands, “What do you think of my show?”

I looked around the gallery as “the show” rapidly disappeared out the door. At the time I did not know what to say. I had nothing to reference the exhibition to. Maria Abramovic was still an unknown young woman in Belgrade, and Tracey Ermin, hadn’t even been born yet.

“An interesting idea,” I said in a rather non-committal manner, not wanting to get into a discussion about the work at the moment. I would leave that to his thesis committee, of which I was not a member.

“But you haven’t taken anything, professor . . . that’s part of the show. Help yourself before there’s nothing left.”

“No thank you, Bob,” I said calling him by his given name. “I don’t need anything right now. Besides, what are you going to do when all your things are gone?”

“No problem, I’m graduating . . . leaving town. I’ll just get new stuff wherever I end up. It’ll be less to move.”

I had no idea what Chain Man’s circumstances were, he seemed a little bit older than the average graduate student, but the thought of having to replace all his possessions didn’t seem to bother him much. Or was this just a ploy; Chain Man’s clever way of getting rid of what he didn’t want while he still had an apartment full of good stuff?

Glancing around the room, I wondered how well stocked Chain Man’s store had been when it opened about a half hour ago, as all the items now lining the wall could be loosely defined as junk. The students presently rummaging through the exhibition seemed to be regarding what remained mainly with curiosity. Perhaps these were the more affluent ones, the needy having already grabbed and ran with the things of value. A stack of pornographic magazines was getting many lookers but no takers. But then Chain Man himself was standing there stark naked.

“Here . . . take these, professor,” Chain Man said, handing me two tan chino work shirts.

“No thank you, Bob, I have plenty of shirts . . . I’m sure that someone else could use them better.”

“But I want you to have them . . . something to remember me by. You see, these are magic shirts.”

“And how are they magic shirts? . . .”

“Take them home with you and you will discover their magic. . . .”

And so I took them. That was the spring of 1969. I still have the two shirts. I don’t wear them to classes anymore as I am retired. However, I wear them when I am working in the yard, as ever since the deer ticks arrived we dress in light-colored clothing. The shirts still show little sign of their age. I am not sure if that is because they are truly magic, or because their label says: Made in the USA.

And what became of Chain Man an artist who was apparently quite ahead of his time? His name, as I recall, was Robert Ely. Unfortunately, we didn’t keep in touch, so I never heard of him again. A recent Google search revealed nothing. All I have to remember him by are my magic shirts.

About the Author

Stephen Poleskie is a writer and an artist. His writing; fiction, poetry and art criticism has appeared in journals in Australia, Czech Republic, Germany, India, Italy, Mexico, the Philippines, and the UK, as well as in the USA, and in the anthologies The Book of Love, (W.W. Norton) and Being Human, and been nominated for a Pushcart Prize. He has published seven novels. His artworks are in the collections of numerous museums, including the MoMA, and the Metropolitan Museum, in New York, and the Tate Gallery, and Victoria and Albert Museum in London. Poleskie has taught or been a visiting artist at a number of schools, including: The School of Visual Arts, NYC, the University of California/Berkeley, MIT, Rhode Island School of Design, and Cornell University, and been a resident at the American Academy in Rome. Poleskie currently lives in Ithaca, NY with his wife the author Jeanne Mackin.

Website: www.StephenPoleskie.com

I really like this story. Steve has a way with remembering details like an elephant, and he is very clever and funny. I wish I had one of those “magic shirts ” !!

What a great story. Where can I get one of these shirts? I don’t mean the magic part, just one that has a label that says “Made in the USA.”