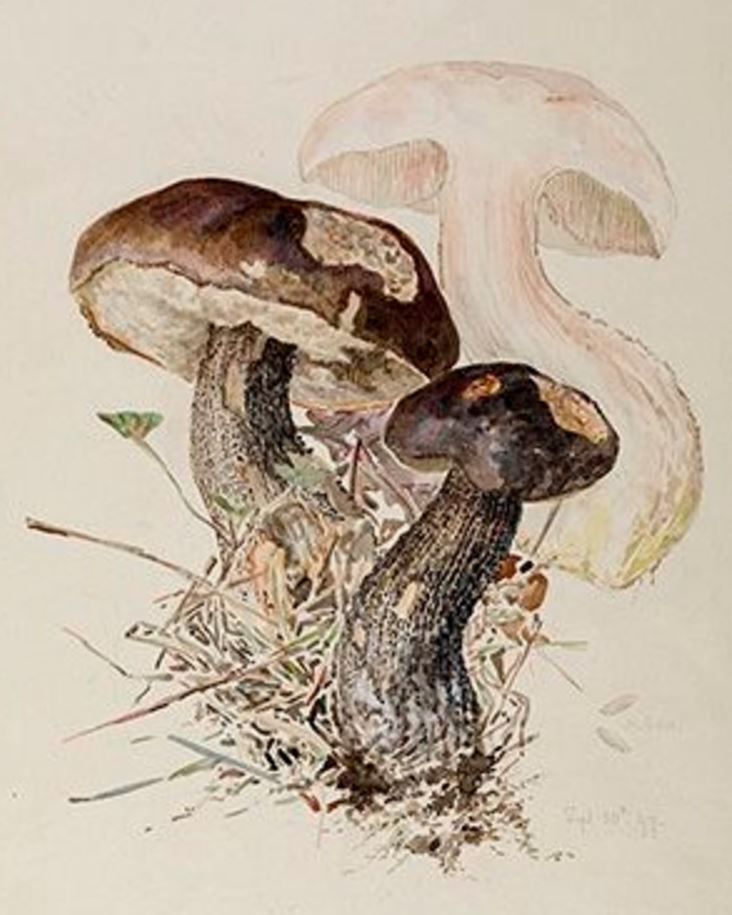

Ohio-State Plant-Pathology saved to Plant Disease Art Watercolors and work of Beatrix Potter in the fields of botany and mycology

THE ORE HOLE

By Thaddeus Rutkowski

During a school day, a science teacher took my class on a field trip. We hiked to a patch of trees growing in a crater in the ground. “This was an ore hole,” he explained. “Iron ore was dug here; then it was blasted in a furnace and shaped into pellets. That’s what made this area rich.”

All we could see were trees growing in a pit. In one section, people had dumped their garbage. Bottles, cans and other non-degradable items lay on the surface of the fill.

As we walked through the leaf cover, a girl announced that she saw a penis. “It’s sticking up,” she said.

“Where is it?” the teacher asked.

The girl pointed to a whitish, erect object on the ground. Around the base of the object was a dark-brown sheath.

“It’s a mushroom,” the teacher said, “It might be edible.”

On closer inspection, the mushroom turned out to have an unpleasant smell. No one would touch it. We left it where it was.

*

In the evening, my parents started to argue about something—I couldn’t tell what. I tried to watch television with my brother and sister and not listen to my father’s voice.

“You’ve turned them all against me,” my father said. “You’re all against me, you and your chink children.”

I knew what he meant. My brother and I didn’t resemble him. We looked more like my mother.

My sister, though, looked more like my father. Her eyelids didn’t have folds of skin like ours. Her eyes were like a white person’s eyes. Further, the irises of her eyes weren’t brown, like my brother’s and mine. Her irises were gray, like our father’s.

But that wasn’t what my father meant. He meant that none of us would put up with his behavior.

When I couldn’t hear his voice anymore, I realized he’d left for the local bar.

*

In the morning, I got on the school bus and took a seat next to an empty one. When the bus reached the highway outside town, it stopped for a boy on the side of the road. He was standing in front of a small, green-shingled house with a tar paper roof. The house looked like it was resting on a platform or stilts.

There were no open seats except for the one next to me, so the boy sat there. He seemed to be a couple of years younger than I was. “I have a gun,” he said to me.

“What kind?” I asked.

“A single-shot .22.”

“You only get one chance with that,” I said.

When a seat opened up away from me, the boy moved.

*

I handed in a report about the penis my class had found in the woods.

When I got the paper back, I saw that the teacher had addressed me as “Flip.”

“You might think you get it, Flip,” the teacher wrote, “but you don’t. This is cruel, without humor.”

I showed the paper to the girl who’d found the penis.

“I like it,” she said. “I like all of the papers you write for class.”

*

After dinner, my father took some aspirin with his beer. “I’m taking the whole bottle,” he said. “If I take enough, I might die.”

I didn’t want him to swallow the pills, but there was nothing I could do to stop him.

He went into his studio—a dark front room shaded by a porch roof—so he could consume a lethal dose in privacy.

Presently, he came out and said, “I took the whole bottle.” He waved the empty container to prove it.

I waited to see if he would die, but he didn’t appear to be dying. He had some life in him. He energetically left the house and headed for the local bar.

*

The next day, I walked out of the house and turned off the paved street. I followed a lane until I got to the creek. Along the bank, I saw a clump of mushrooms growing from a dried pile of cow dung. They looked more like toadstools than mushrooms. I pushed one with my toe, and it broke off at the base. Its roots came out with it. This fungus, I decided, might belong to a psychedelic variety.

I took some specimens home with me. The thing was, I didn’t know how to consume them. I thought about chopping them up, chewing them and swallowing them. But they didn’t smell appetizing, probably because they’d been generated from dung.

So I decided to melt some chocolate. I threw a handful of chocolate chips, the kind meant for cookies, and into a saucepan and turned on the heat. When the chocolate became liquid, I threw the mushrooms in whole and turned off the heat. I waited until the chocolate hardened into a slab of magic candy.

*

My brother told me the boy from the tar paper house had been taken away. My brother knew him because he was in the same grade as the boy. “He tried to shoot himself with a .22,” my brother said. “It was a single-shot.”

“What happened?” I asked.

“He pulled the trigger and missed.”

“Where was it?” I asked.

“At the ore hole. He was sitting in the trees with the rifle until they came looking for him. He said he wanted to go to the bottom of the pit.”

*

I ate the electric Hershey bar, but I couldn’t tell if the drug was working. The mushrooms, I thought, might not be psychedelic. They might be common cow-patty toadstools.

I tried looking at my father’s paintings in his studio, and I had an insight. I would never be able to forget the images. I would see in my mind’s eye giant insects, biplanes, zeppelins, naked dolls, naked people, antique bottles, miners in gas masks and hand-drawn grids. I had to get out of the studio. I had to find a place that was quiet, where nothing would assault my senses. I couldn’t go to my room. It was lonely there. I found my brother and sister, but I couldn’t tell them I was tripping on toadstools. I just sat with them while they watched television. But the dialogue with canned laughs was too much for me.

I got on my bike and started pedaling. Presently, I came to the ore hole. I sat in the trees and batted at gnats. The ore had been plentiful at one time. It was dug, smelted, and made into steel. People got rich. Five steel men from the nearest big town became governor of the state. Now, the pit was a garbage dump. I kicked some leaves away from a pile of debris and found some antique bottles. One was for Lydia Pinkham’s Liver Cure—the brand name was embossed on the side. I would take that bottle home for my father to use in a painting. I dug some more with my foot and found a child’s doll, naked, with cracked plastic skin. I would also take that home for my father to examine.

- “Hard Biking” is one of the stories included in the recently released collection Guess and Check, from (Arlington, VA) Gival Press. Includes work praised by John Barth as “ . . . tough and funny and touching and harrowing.” Described in Kirkus Reviews as, “A stark, engrossing, Hemingway-esque portrait of a life spent in the margins.” Another story from the collection, “Out of Fashion,” can be seen here: http://old.ragazine.cc/2013/04/rutkowski-fiction/. It is reprinted here with permission.

About the author:

Thaddeus Rutkowski grew up in central Pennsylvania. He is the author of the books Violent Outbursts (Spuyten Duyvil Publishing), Haywire (Starcherone Books / forthcoming from Blue Streak Press), Tetched (Behler Publications) and Roughhouse (Kaya Press). Haywire won the Members’ Choice Award, given by the Asian American Writers’ Workshop in New York. He teaches literature at Medgar Evers College in Brooklyn and fiction writing at the Writer’s Voice of the West Side YMCA in Manhattan, where he lives with his wife, Randi Hoffman, and their daughter, Shay. He received a fiction fellowship from the New York Foundation for the Arts. Visit him at www.thaddeusrutkowski.com.

Thaddeus Rutkowski grew up in central Pennsylvania. He is the author of the books Violent Outbursts (Spuyten Duyvil Publishing), Haywire (Starcherone Books / forthcoming from Blue Streak Press), Tetched (Behler Publications) and Roughhouse (Kaya Press). Haywire won the Members’ Choice Award, given by the Asian American Writers’ Workshop in New York. He teaches literature at Medgar Evers College in Brooklyn and fiction writing at the Writer’s Voice of the West Side YMCA in Manhattan, where he lives with his wife, Randi Hoffman, and their daughter, Shay. He received a fiction fellowship from the New York Foundation for the Arts. Visit him at www.thaddeusrutkowski.com.

Photo by Buck Ennis.

Recent Comments