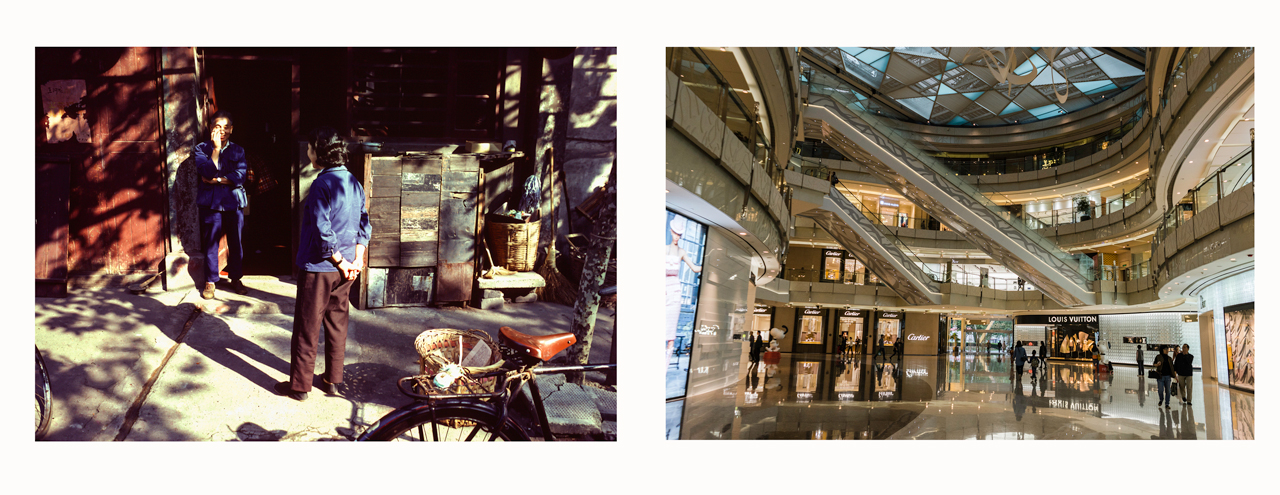

Miss Shu 1980 | Neon Babe 2014

………………………………………………………………………………………………….………………………………………………………………………………….

MAO to NOW

A photographic exploration of change

f

by Steven Verona

In 1980 I was sent to China to direct a movie staring Ingrid Bergman. It was to be the first American-Chinese co-production in over forty years. Filming was to take place in Peking (now called Beijing), Hangzhou, Suzhou and Shanghai. It was mid- September-early October and the weather was beautiful. I had never been to China nor had my friends, and I was very much looking forward to being in an exotic locale on the opposite side of the world.

I was met at the Shanghai airport by two cars containing my Chinese contingent, who were to be with me during my entire stay: Mr. Wong, head of the Shanghai Film Studio, Miss Shu, my interpreter, Mr. Coo, a famous actor, General Huong from Beijing, a neatly dressed army official, clearly in charge. He seemed like a man you would not dare go against. Luckily I never had to. And then there was the driver. He rarely spoke. I immediately nicknamed him “the Animal.” We were on our way to the Bei Wei Hotel.

The roads were large and for the most part empty. Bicycles were everywhere. Everyone seemed to be going at the same pace and there was a constant ringing of little bells.

As we pulled to the front entrance of the hotel, I encountered my first problem: it was dark and appeared dirty – no place for a Westerner to stay. We walked through the front door, and I immediately told my new friends, “I can’t stay here. And I can’t bring an American crew to this hotel.” Mr. Wong said, in perfect English, “Call me Larry.”

Immediately, the group began whispering in Chinese. Then Larry said, “We will find you a more suitable place.” We got back in the cars and headed for the Jing Jiang Hotel, a large colonial-type building in the French Concession, where I was ushered into President Nixon’s suite. This is where he stayed in 1976 when he came to open China to free trade with America. There were pictures of him on every desk, dresser and table. I put them away and attempted to make the room my own.

I was up early the next morning and grabbed my camera. I was a compulsive picture taker and still am. I started investigating small neighborhoods, people, shops, smells all the while snapping picture after picture. I was in heaven. Even at that early time of the morning there was a flow of people on bicycles and people doing Tai Chi. I noticed how everyone was wearing the same blue or gray baggy Mao outfits. It was very quiet except for the gentle ringing of bicycle bells.

After a short time I had the feeling I was not alone. When I got back to the hotel for a nine o’clock meeting, Larry told me that “they” watched me to make sure that I would not get lost. Hmmm.

We officially began the day walking around the French Concession. The streets were lined with trees, and the architecture was in the French Chateaux style. As we walked and I took pictures, Mr. Wong told me an interesting story: He used to live here in the French Concession in a ten room chateau. He worked as one of the heads of the Shanghai Film Studios with his family until they were thrown into prison in 1966 at the start of the Cultural Revolution because they were deemed intellectuals by Chairman Mao and the Gang of Four—simply because they could read and write!

Larry spent two and a half years in solitary confinement, where he spent the time taking apart his watch and putting it back together. He then spent two and a half years on a hard labor work farm, followed by five years in prison. Ten years later at the end of the revolution, Larry and his family were released and permitted to live back in his ten room chateau. However, as it had become a porcelain sink company, he was relegated to two small rooms in the back for him, his wife, his daughter, her husband and their baby. And he was grateful, never angry or spiteful.

Mr. Coo, the actor, didn’t speak English, but everyone seemed to recognize him in the street. He would tip his hat in gratitude.

General Huong continually made sure we didn’t film anything we shouldn’t, while the diminutive, soft-spoken Miss Shu interpreted. The Animal drove us everywhere. I wondered sometimes if he was also a sort of bodyguard, as he was huge and silent. It took him a week before he began to nod and smile my way.

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..

Stephen paired photos he took in 1980 to his recent trip back to China.

Visiting 1980 | The Mall 2014

All photos © 1980-2014 Stephen Verona | Used with permission.

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..

Shanghai was primitive. People sold things on the sidewalks and the Bund was the waterfront trade. It reminded me of old black and white films from the fifties – a place you would not want to walk alone at night.

I brought money with me, as I wanted to buy antiques and souvenirs, but I couldn’t because they didn’t accept dollars, only friendship money, and there were no credit cards. The antiques had been confiscated, lost or destroyed during the revolution. The only thing I was able to bring back were Mao buttons, which were gifts from Larry. They were little pins with pictures of the Chairman. I have them in porcelain, wood and metal. They are now framed and hanging in my studio.

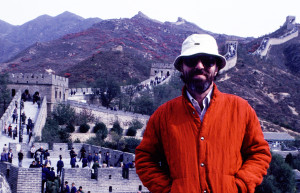

We continued to scout for locations throughout the city and then onto Suzhou where I photographed the old town and the canal running through it. From there we moved on to Beijing and the Great Wall, The Temple of Heaven, the Summer Palace and the Forbidden City. All were phenomenal places to shoot and empty of people. It seemed they opened it just for me. The days were clear and beautiful.

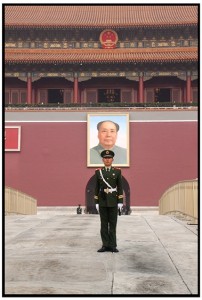

We continued to Tiananmen Square, then to the various alleyways, markets and stores of Peking/Beijing. Just as I was about to finish location scouting, the news came that the movie fell through. We lost Ingrid Bergman, who had become very ill, and the financing dropped out. I was heartbroken as I loved the story and of course had found so many wonderful locations that I had photographed. I stayed on in China for a short time and continued exploring and shooting pictures because I loved China and was hoping that a miracle would happen and the film would come back to life.

I was so smitten by what I had seen that when I returned to Los Angeles, I began to paint what I had photographed. I have since phased out my active role in the movie business and have spent the last twenty years making art. It is now my photography that gives me the most joy.

Several months ago I was thumbing through some old pictures of China and thinking how rapidly the world is changing. And no where is change more apparent than in China. When Nixon opened up that door it seems he opened a floodgate. China took the ball and ran with it, and while other countries went to war, China built infrastructure and towering cities.

I decided I had to go and see the country again to observe first hand the changes that had occurred in such a short time. I became excited about a journey I would call “MAO to NOW”. So we left Los Angeles in late October 2014 – 34 years after my first experience and headed for Beijing.

It was late when my wife, Ann, and I finally arrived and the new airport was completely empty – no cars, bicycles or taxis – just this big empty, cavernous airport. We were able to find someone in a car service who spoke a little English and could take us to the Fairmont Hotel.

The concierge was warm and welcoming and showed us to a beautiful luxury suite complete with a cappuccino maker, a toilet that washes you and a smaller TV in the wall above the bathtub.

The next morning I opened the shades to look at the city. You could barely make out the buildings across the street due to the pollution. I went downstairs to meet my cousin’s son, Brandon and his girlfriend, TingTing, who were going to help us get around, as very few people spoke English. We walked first to the subway.

Our first stop was the new art area, a section of town called 798. Originally a munitions factory, the compound had been renovated into huge city blocks of artist studios, museums, and galleries, including Pace, one of the top galleries in the world.

One could see could see a freedom of expression today that was not there in 1980 – pop art, sculptures and inventive paintings. The streets had been given over to graffiti artists – no spray paint scrawl, but majestic paintings on walls and shipping containers. I was very taken by the brilliance of the work and found myself wishing we had more of these kind of art spaces in America. It was very inspiring.

We took a taxi home in a sea of red tail lights – traffic jams. It was hard to breathe. What should have been a ten-minute car ride took almost an hour. Some drivers sit and text and email their friends while others try to cut through cars inches at a time then zoom down pedestrian walk ways while bicycle riders jump out of the way. Interestingly, all the cars seemed relatively new. There were no beat-up cars on the road, although we saw many fender benders.

Today throngs of people crowd into the Forbidden City. The Summer Palace was filled with tourist groups waving flags. And The Great Wall was so full of shops it reminded one of Main Street, Disneyland. These attractions had become big money making businesses.

Shanghai was even more advanced. There were massive hotels, office buildings and multimillion dollar condo complexes everywhere. High end restaurants and shopping malls were on every street corner. Gucci, Louis Vuitton, Chanel, Tods, Prada— all these stores were in duplicate, triplicate. They seemed to go on and on. It’s as if the people have so much money they shouldn’t have to walk more than two blocks to buy whatever they could possibly want.

The Chinese I found to be happy, warm and smiling. Most looked at you like they had never seen a white older bearded man from California with a blonde wife. They were fascinated by us and sweetly approached and asked if they could take our picture. They put their arms around us, hugged us, and asked if we would pose with them for a picture. There were very, very few cameras back in 1980, as people could not afford them. Now the Chinese love to take pictures with their smart phones.

Another thing the Chinese love is their children. Because of the one child policy in China, a child is treated almost like a deity – practically worshipped. I fell in love with the children. When I took their picture, the parents grew very excited and posed them. They were all so proud and beautiful.

Women walked alone on the streets at night. China was probably the safest place I had been. There was no feeling of oppression or of being watched, although I was told that one still had to “watch what one says.”

In the end, I came home with the idea that at least with China, rapid growth is a good thing. And although I still saw people washing their clothes and dishes in the canals, some of these same people had flat screen TV’s inside their humble abodes. I still saw lots of bicycles overloaded with boxes, women travelling with four children on loaded-down Vespas. At the same time there was either a factory or new construction going on every few hundred feet.

Sadly, some of the little vendors have been replaced by McDonald’s or Starbucks. But behind the gargantuan buildings that perform light shows every night, one can still see the quaint streets and tiny shops selling their wares. The new China is backing up against the old, as change becomes more and more inevitable.

I have done the best I could to retrace my steps from then to now, but it was nearly impossible. The people I new then are gone or lost. The landmarks maybe the same, but the people who visit them dress differently – more colorful, more interesting, more fruitful lives, perhaps?

You decide. “MAO to NOW” is not a political statement, nor is it a cultural questioning. It is simply a visual documentation of the evolution of a people. It is a study of contrasts, of time passing from primitive to sophisticated, from isolation to exposure. Draw your own conclusions.

f

About the Author:

Website: stephenverona.com

There is a saying that ONE PICTURE IS WORTH A THOUSAND WORDS.

The same is true with MAO TO NOW.

A beautiful pictorial analysis of an ancient civilisation that has undergone dramatic industrial and technological change yet Verona focusses in on the irony that the culture remains intact inspite of this and the pressures of 20th century politics. A remarkable achievement by a world class photographer.

This is Fabulous work! And, it is interesting as I reflect on the journeys I have been on…and how things are changing so rapidly. A beautiful pictorial no doubt but above all, Thank you for sharing. Brilliant!

Fabulous? Pictorial? Remarkable achievement? Not a cultural questioning? The idea (China then and now) is very clever, the execution hardly. It’s travelogue, and it bears the stamp of the writer’s preferences and prejudices–Mao is everywhere preferred to now. It would be a very engaging read if Verona had owned his point of view a little more honestly.