Car Sales by Emilio Labrador

The Car Salesman

By Sidney Thompson

Driving onto the acreage of Hank Hood Automall made Cooper Young instantly anxious. Threat seemed to lurk everywhere, and the carnival dressing of balloons, tents, and pennant strings suggested major cover-up.

Now this: at the entrance to the main customer parking lot in front of the GMC/Buick/Pontiac building, a silver luxury conversion van was parked in display with its doors open, and as Cooper drove past, he caught sight of four guys seated inside—all wearing white polo shirts and laughing, yet all keenly aware of him, their eyes following in his direction until he was out of view.

He pulled into the space closest to the building and glanced back at the van, expecting to see salesmen swarm, but not one of them bothered, even slowly, to climb out to greet him. It was as if suddenly, at 2:55 p.m., thirty-five-year-old Cooper had ceased to exist.

In the rearview mirror of the only automobile he and his wife owned, he nudged his tie as if gauging its evenness, but he was thinking only of his wife, Leah. He wasn’t remembering her elegantly stretched figure on a yoga mat but Leah looking at him how she’d looked at him for hours yesterday once he told her he’d lost his job—with longing and judgment and sustained disappointment.

Two cars angled to a point on the showroom floor for Cooper’s immediate attention, or someone’s immediate attention, with just enough space between them for customers, or applicants, to pass through single file. He only vaguely noticed their metallic shine as he made his way to the front desk, where two women sat and a phone rang.

The woman on the left, a silver blonde in her fifties, with the dark, aged skin of a tanner and smoker, answered the phone in a booming singsongy Alabama drawl, “Good afternoon, Hank Hood Automall, this is Vicky, how may I assist you?” The teenage brunette on the right, with the short asymmetrical haircut of jagged lines and the square shoulders of a model, with her head tilted down and her face hidden, appeared busy with a black rollerball, clutched like a chopstick.

“Just a moment,” said the Vicky, and after pressing a transfer button and setting the receiver down, she made eye contact with Cooper for the first time and forced a smile. “Yes, how may I assist you?”

Her voice was so loud and sternly assertive that for a split second he didn’t know what to say. The younger one raised her head as if to see what the commotion was about. Her eyes pure azure.

“I, uh, have an appointment to see Jimmy Bertella. I’m Cooper Young.”

The Vicky lowered her head, opened a desk drawer, and pulled out a box of Cheez-Its.

“No, thanks,” he joked, hoping to lighten the mood, but the Vicky ignored him and so did the young girl, whose attention returned to a cream-colored pad of doodled paper. Dark Spheres and arrows.

The Vicky reached back into the drawer and withdrew an employment application form. “Have a seat over there and fill this out.” She slapped a pen on the desk, but he patted his breast pocket to show her he had his own, and her face lit up. “Wow, that’s impressive,” she said. “You thought to come prepared. That’s a first.”

Cooper tucked the application form inside his portfolio and the portfolio underneath his arm before thanking her. He found a seat beside an aquarium of small earth-tone fish hiding among shelves of rock. He didn’t know how to explain his reason for leaving Bouchard Academy, where he’d taught freshman English for the last three years, so he opted to keep that portion blank.

When Cooper returned to the front desk with his application, the Vicky took charge again, picked up her phone, and buzzed Jimmy Bertella. “Cooper Young is here to see you for an interview.” She hung the phone up. “He’s on his way, but let me tell you this first,” she said, leaning forward and pointing at Cooper with a nail lacquered hot pink, “if you’re to work here, I’m warning you, you’re to leave my girls alone. Sexual harassment will not be tolerated.”

“Of course,” he said, avoiding eye contact with the young girl.

“As long as that’s clear,” she said, sitting back in her chair with superb posture and reaching for another Cheez-It.

Cooper heard quick footsteps behind him, so he turned and was met with a vigorous handshake.

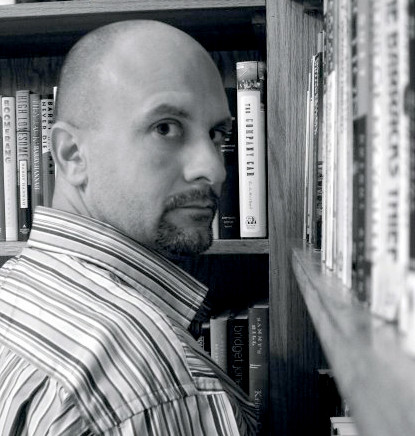

“Jimmy Bertella,” said the barrel-chested man stepping in closely to introduce himself. Even with his affable smile and animated body language, there was an intensity about him that was undeniably ferocious. He had small eyes and thin lips. His thick, moussed-back, raven-black hair and neatly trimmed goatee had the finest of gray streaks, like tinsel.

“Cooper Young,” Cooper answered, and although Jimmy Bertella continued to pump his hand, his attention began to stray toward the women at the front desk, and then he let go of Cooper’s hand to reach for something, maybe the employment application lying on the desk, but no, his hand went behind the desk and returned with a Cheez-It, and he popped it into his mouth.

“Has either of you tried the new Cheez-It?” he asked.

The young brunette raised her head in a jerk, her blue eyes wide, almost deep, in amazement. “There’s a new Cheez-It?”

“More like a potato chip,” said Jimmy, “but better, really cheesy.”

“I’ve seen it,” said the Vicky, “but never tried it. But I’ve seen it.”

“Huh,” said the younger one.

Jimmy licked his fingertips, brushed them across his slacks, then collected the application, giving a glance at the Car Sales History and Felony Conviction Notification sections. He regarded Cooper and patted him on the back. “Follow me.”

He led Cooper to an office that faced the highway and the entrance and the conversion van.

“Have a seat,” said Jimmy, pointing to the chairs in front of his desk, and once Cooper was sitting, Jimmy sat, too, and folded his hands on the desk top. “We put the ad in the paper because here in my department, in the GMC/Buick/Pontiac building, we’re one salesman below where we’ll need to be for Memorial Day weekend coming up, which can be the biggest weekend of the year in the car business. So assuming we can get you trained and ready in a week, assuming all that, seeing as you don’t have any experience in retail, I’m wondering, is this really what you want? You know what people think of car salesmen, don’t you?”

Cooper laughed nervously.

“We rank below lawyers and politicians,” said Jimmy. “We’re scum.”

Cooper stopped laughing, and nodding thoughtfully he began to reel off a rehearsed speech about his high marks and academic interests in college, a mere three credits shy of a minor in philosophy—his segue into his teaching pedagogy and classroom management practices, as informed by his experiences first as a grad assistant, then an adjunct, and finally, most recently, a high school teacher at nearby Bouchard Academy, an obvious signpost intended to announce to Jimmy that Cooper had physically and temporally come full circle to the present and was prepared to answer the initial question, now properly framed: “As a teacher, I’ve endured a lot of abuse. English is far from being everyone’s favorite subject.”

“I hated it,” said Jimmy. “But, you know, I don’t know why. I probably read three, four westerns in the john here a month.”

“Wow, good for you.” Cooper nodded, then Jimmy nodded. “So, for the bulk of my experience, for eight years, I received very little pay and no benefits. Really, in teaching, there’s no respect either. But despite all that,” he said, opening his portfolio, “I’ve consistently received overwhelmingly positive student evaluations. You can see by my scores and samples here,” he said, withdrawing a stapled bundle and setting it on the desk in front of Jimmy. “And I’m confident, sir, that with my proven communication skills, I will succeed as well at Hank Hood Automall.”

Jimmy’s gaze never left Cooper’s. “So Bouchard Academy wasn’t any better?”

“Well, it’s its own environment.”

“I hear it’s pretty hoity-toity over there. What’d you do, realize you were slaving yourself to the bone for a bunch of ungrateful snoblets, or did they run you off because you tried to teach ’em something?” Jimmy’s pupils dilated to twice their size. “What, you can tell me.”

Cooper started to believe it was impossible to convince this man of anything untrue. His shoulders flagged. “It was an innocent misunderstanding. Have you ever read A Separate Peace by John Knowles?”

“Missed that one.”

“Well, it’s got a ton of gay references, all subtle for ninth graders but clear phallic imagery throughout. Wooden towers, guns, apple trees, leather-covered balls, sensual winds, naked emotions, the list goes on.” Cooper didn’t know where he was going, but he couldn’t help himself now. The cat was out of the bag. “The headmaster told me when I was hired to prepare those kids for Harvard and Yale. Well, they can’t go to Harvard and Yale without knowing how to read what they’re reading. I didn’t choose the text. The department chair did, and the headmaster approved it. So I thought the kids ought to know what those phallic images amounted to, so I did a stupid thing, I guess. I defined phallus for them.” He gave Jimmy an embarrassed half-smile. “Spelled ‘penis’ on the board in big phallic letters. You should’ve seen those fourteen-year-old girls. Their mouths literally dropped open. Same reaction in every class.”

“I have a fourteen-year-old daughter,” said Jimmy. His jaws flexed and his face flamed red, the headmaster’s exact reaction, until he broke character and laughed. He glanced down at Cooper’s paperwork. “I don’t need to read any of this. Penis, that’s priceless! Their mouths dropped open, huh? Just involuntary?”

Cooper offered a sheepish grin.

“So you fucked up, big deal, but why all of a sudden be a car salesman?”

“I don’t know.” Cooper realized he was slouching, cleared his throat, and sat up in his seat. “Obviously, my background’s in education. I’ve never been interested in cars, ever. But I like to learn, and I want to learn to be a car salesman, Mr. Bertella. I don’t know why. Maybe it’s the challenge of it, something I’ve never wanted to do, but I think I can do it if you give me the opportunity.”

“Sounds like you want to learn to be different.”

Cooper smirked. “Maybe.”

“You’ll be called a liar and a crook to your face.”

Cooper thought of his students over the years, one or two in every class who’d mumble and roll their eyes. “I can handle it.”

“I need to know you can keep your cool under pressure.”

“I can. I have.”

“Rough language doesn’t offend you, though?”

“Oh, no, sir,” said Cooper.

“I used to be in the Army—see here,” Jimmy said, stretching his arm and tapping the 4 x 6 picture frame sitting on his desk by the wall. “Me and my Ranger buddies from Company C at Wadi Kena, Egypt, our command center.” He watched Cooper study the photo, the men shirtless with boots untied, grinning, some standing, one straddling a motorcycle, with pale blond sand and rocks all around, a color Cooper associated with manila folders and ancient mess. “I’m the good looking one on the motorcycle by the way. We look happy, don’t we? Hopeful.”

Cooper nodded.

“Except a couple days later our mission failed, a total bust, a world-class bust. We were hoping to free the hostages in Iran but got mockery and humiliation instead. So think about what you’re asking for and what you might get. Sometimes we really let loose around here because we have to.”

Copper held up his hand for him to go no further. “I can let loose, too, believe me.”

Jimmy pinched his lips together in an expression that mimicked a frown, then from his shirt pocket he withdrew a gold Cross pen that reminded Cooper of the one that he’d received from his parents, just like it, as a high school graduation present. Jimmy held the pen delicately by the ends, with the tips of his fingers, as if it were a joint. “How much money are you expecting to make your first year?”

Cooper looked up from the pen to Jimmy’s dark brown eyes. He hadn’t prepared himself for that question. He only expected to make at least what he made at Bouchard. “Thirty thousand, at least thirty.”

“Shit, I’ll fire you if that’s all you make. You should earn more like forty-five to fifty your first year. After that, it’ll only get higher, with referrals and repeat customers. Orlan Jones’s been with us for fourteen years, and he’s making a hundred and twenty.” He nodded. “In the car business, it’s like you’re working for yourself but without the risk. We pay for the advertising, cover all overhead, and provide you with the inventory. All you have to do is show up and work. Can you handle that?”

“Oh, yes, sir,” said Cooper.

“Now, we’ll give you a salary of three-fifty for your training week, but after that, you’re on your own, strictly commission. You’ve never been on commission before, have you?”

Cooper shook his head.

“You’ll get ten percent of the front-end gross, what you and I manage to hold onto ourselves when we pencil a deal and close them down, and then another five percent from the back end, what the finance manager makes in the box off points and extended warranties, gap insurance, stuff like that. And then there are bonuses for hitting certain unit levels. Once you sell five cars, you get $100. Sell eight, you get another $100. Sell ten, you get $300. Now, that’s on top of the commission. It keeps growing. At thirteen you get $500, at fifteen you get another $500, and at twenty, it’s a grand. Hit all those unit levels, and in one month you’re making $2,500 in bonuses alone.”

Cooper smiled and kept smiling, his smile really stretching itself. As a teacher, he’d never been given the opportunity to earn his worth, never even encouraged to dream of it. Then Jimmy wrinkled his brow, and Cooper’s smile slacked as he watched Jimmy lean forward, cradling the pen in his hand, with the tip of the pen pointed at him. Jimmy looked as if he were about to write on the air between them.

“Cooper,” said Jimmy, “can you handle the guilt people will try to lay on you for wanting to make a little profit? Now, they don’t fuss about the outrageous 100-percent-and-up markup on clothes and jewelry and cereal and shit, but we’re assholes for asking for a humble 10 percent, and then bigger assholes if we drop it all the way down to 5 or even less, the way homebuilders won’t, the way pharmaceutical companies won’t, the way hospitals won’t, because that says we’re playing games, that we shouldn’t have asked for so much gross in the first place. So what I want to know, Cooper, is do you have an answer in your heart for logic like that? I mean, how will you protect yourself?”

Cooper was silent long enough to make Jimmy wonder if he would answer honestly. He was beginning to wonder himself if he’d find anything to say, honest or not. Apparently, Jimmy was not going to speak next to move things along. He was waiting, with his pen still pointing at Cooper, for an answer.

“Mr. Bertella,” he said, just to say something, to get the words flowing, “my wife and I,” deciding to start at the beginning, “we’d like to buy a house and eventually have kids, you know. It’s a pretty pedestrian goal, but there you have it. We need money, and I deserve to make money, I think. Like everybody else.”

Jimmy pinched his lips together again. His head rocked almost imperceptibly. Then he set his pen down so that he could interlock his hands and rest his arms on the desktop. “You’re a car salesman, Cooper Young,” he said without blinking, and then he laughed without a sound. “I can see that about you. Saw it immediately. Look at you. You’re a car salesman. Look how you’re dressed. How I’m dressed. We look neat and professional, don’t you think?”

Cooper nodded but didn’t quite follow. He was wearing what he’d worn many times as a teacher, or had he been more of a salesman all along instead of a teacher? What exactly was the difference, and how did it show? Could it show?

“A professional wears a tie, not a goddamned golf shirt, for chrissake,” said Jimmy. “You can choose, though. We give you a choice. Over at Parts, you can buy the golf shirt with the Hank Hood logo and wear that with blue or khaki shorts or long pants, no jeans, or you can dress dignified like us, but you tell me, Cooper, who do you think a customer would want to work with? Anybody else around here?” He turned in his chair to scout the terrain outside, but Cooper didn’t see anyone. Jimmy pushed against the arms of his chair, and on his feet he scanned the showroom. “What the hell!”

Jimmy eyed his recruit. “Come on, follow me.” He darted to the next office, where two desks, positioned side-by-side and each with a computer, faced a plate-glass window overlooking the parking lot and Cooper’s lone Jetta. From the nearest desk, with a clatter, he snatched the telephone from its cradle and pressed the Page button: “All new-car salespeople without a customer come to the sales tower.” He repeated himself, louder that time, then set the receiver down.

He folded his arms and waited, then when they started to appear, passing in front of the plate-glass window, Jimmy pointed, one by one. “See what I mean, Coop,” he said. “See what I’m dealing with. Look at Roy—he never takes the time to iron his fucking pants. And look at Garrett—what a slob. Look at the sweat stains under his arms. You have to wear a T-shirt in this business, Coop. It’s a must. And look at Shane, with his shirt coming out in the back. And Bret, with his fucking cowboy boots. And look at Tony—he’s sloppy but he’s closer, he’s almost got the right idea, but do you see what’s on his tie? Fucking Tabasco bottles, Coop. Fucking Tabasco bottles, the little smart-ass. What the fuck! Slobs, every one of them. So I’m glad you’re on board, Coop. I’m glad you’re on board. You’ll grow up quick here. Shit, you’ll see, in no time at all your wife will have her precious little Pottery Barn house and her tennis lessons and rose bushes and shit, and you’ll be hitting that fine young thing at the front desk, along with the tail in BDC. That’s the Business Development Center, the girls who send out letters and make calls to make you and me money. Your days of being stomped on are numbered, you’ll see. You’ll be swarmed with pussy here, Coop, and paid for it, so I’m glad to hear you ain’t attracted to phallic, know what I mean? Shit, you won’t find leather-covered balls or apple trees around here unless you’re really looking for them.”

Ignoring the salesmen gathering in the tower, Jimmy walked Cooper out, saying he’d see him at 8:30 Monday morning, that hours were 8:30 to 8:00, Monday through Saturday, closed on Sundays except for the last Sunday of the month when it was busier, like this coming one, and they had to be open, 1:00 to 6:00, and that everyone got one day off during the week, but never on Saturday, the busiest day of the week in the car business, that everyone worked on Saturday. “Sound good?”

Cooper thought of nodding but couldn’t.

“Great,” said Jimmy. “Enjoy your weekend, and then we’ll see you Monday at 8:30 for the sales meeting. We have ’em every Monday, Wednesday, Friday, and late is something you don’t wanna be.”

Recent Comments