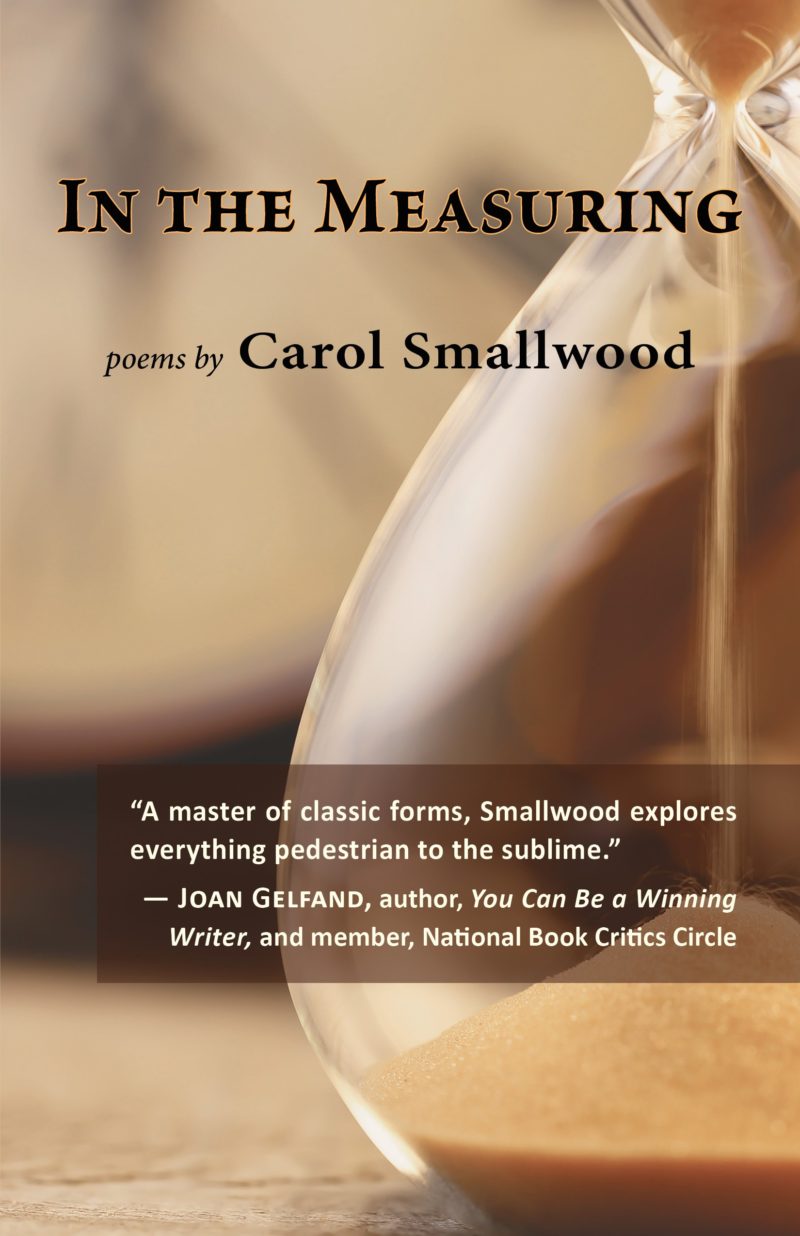

In the Measuring

by Carol Smallwood

Shanti Arts, 2018.

Brunswick, Maine

116 pages, $14.95, paperback.

Available on Amazon.

Review by Ronald Primeau

I

t is often said that we cannot measure what is real, what actually counts or matters most. In The Measuring demonstrates that in the right hands we can do all that and more. For Carol Smallwood, we do not find meaning already made; rather, in the activities of our everyday lives we make meaning in ways that affect how we learn, store, remember, and pass on the truths of our experiences.

This collection of seventy-seven poems is packed with insights set in motion by an epigraph from Emily Dickinson: “The truth must dazzle gradually/ Or every man be blind.” Smallwood is not the first to insist on this “dazzle,” but she is especially subtle in depicting the feel of the crucial gradualness. In so many different ways these poems reveal the gradation of steady and deliberate measurements in the ordinariness of our daily lives. How measuring opens us up to mystery is the book’s organizing motif. “Proof of Transitory” looks at fading and blossoming, dusty shelves and unfulfilled resolve, and how we learn to negotiate the fine line between fading and progressing. From the chemical reactions of making and breaking bread to the sifting through a myriad of dishwashing liquids on a grocery shelf, we face choices in every moment. Some measurements seek us out: the feel of a waiting room after a diagnosis, the funeral-planning postcard that arrives “to resident” and thereby sidesteps the more threatening personal surveillance from the grim reaper. We also experience the information storage system woven into making quilts, a driver in a car wash who is content to settle into “the tracks of those who went before,” measurements so subtle that we feel evaporation and the melting of ice.

Smallwood‘s presentation follows six sections with a precision that is never repetitive or overly rapid. A Prelude suggests that however we arrive at truth, there will always still be mystery in the measuring. “The Domestic” stirs deeper into the ordinariness of rain and leaves, cooking and sewing, light pouring through a window to create shades of gray, efforts to “prove” what we assume we know for sure, discovering that the frustrating efforts to prove something only intensify the thirst for proof. “Sea Change” locates meaning in a shrug or a frown, takes a “Brief Look” at the sublimity of what is ordinary, finds Prufrock measuring his life with cups from fast food restaurants, and catches the subtlest signals missed by all except the most astute “sorters and watchers.” In the brilliant “Shopping Sestina Sans Meter” a shopper envisions everything in a supermarket from her imagined funeral procession at the dairy counter and turkeys in hiking boots, to the perfect biscuits made by the Clabber Girl—all leading to yet another question of measuring: “How much knowing is good for us to know?”

Emily Dickinson (“Tell all the truth but tell it slant’) again provides the title for section four, “Slant,” which reminds readers that measurements must be somewhat circuitous as well as slow and deliberate to create meaning about time, the moon, clocks, tile floors, and the man who calms his wife’s worries about how she can ever list all her ailments. “You’re just supposed to circle things” he assures her. To be gradual, sometimes the dazzling must wander into productive distraction where the profundity of a philosophy class is interrupted by a train whistle that carries “Augustine, Wittgenstein, and the professor neatly away” (91).

Though most often thought of in cooking or construction and generally seen as an accumulation, in Smallwood’s steady hands, measuring is also an acceptance of necessary losses. Symbols of aging are big business with large print and assistive devices signaling a compromised independence (“Arrival, 59”). “Catching On” suggests that felt experience can be squashed by too much “talking out” and that measuring devices—scientific and otherwise—are always “still figuring out what to do with” the ubiquitous mysteries of every day. Again the shopping sestina surveys a restaurant grouping of “always the same men on the same stools” counting out the minutes they have left in talk firmly planted in shoes with “holes that gave them personality” (62). The men reflect back on their lives and ask about the unknowables where even the sage “Know thyself can be a Medusa turn-to-stone blow” burdened with too much knowing (70).

Spend rewarding time with this book and you will find yourself discovering much that is new about what you thought you already had firmly in hand. “In Passing” concludes the volume with some dozen poems that measure “differences in what seems the same” (95), watches closely the processes unfolding in “a Happy Meal Cup of melting ice” (97), transports a bug from the post office floor to nurturing crumbs and to live again in the window plants of home. An “epilogue” creates an apt coda where we live and measure our lives in the halfway between the deepest oceans and the highest mountains.

Smallwood asks many times what all the measuring does for us anyway. Does it find explanations that are already there or create meanings through the often painstakingly slow dazzle of language? Is it all about keeping track of things, deciding how to store and share what we learn, and then struggling with uncertainty? The slow progression of gradations is discovery as well as an acceptance of loss. Blossoming is best in “the struggle of dandelions in sidewalk cracks” that brings more hope than “crowds of daffodils” (55). Here the literary allusions leap beyond Dickinson, calling upon Wordsworth’s “Intimations of Immortality” and suggesting the title of Alice Walker’s very early book Revolutionary Petunias that push their way through inner-city cement. We hail the annual coming of spring with its rite of passage but repress bugs and lawn mowing. It’s all about loss, the measuring—not all accumulation as we hope—but learning to let go and accept diminishment.

Understanding the processes of measuring teaches being at peace with loss. “Ephemera,” from the Greek meaning “living a day” flashes the fast dance of nurturing in which we ignite, mature, and die in an instant. In a measured way, aging is an arrival recognized when people hold doors and smile, when catalogs flood the mailbox, when “large numbered clocks and colorful canes” are offered in the hopes of prolonging independence (59). Yet another measuring of letting go is “A Multigated Acquisition” exploring a test of whether a heart is “strong enough for chemo” (54.) Other speakers reflect on whether—after a hysterectomy–one’s remains are packaged “in a paper sack like the gizzard, heart, liver, neck inside a roasting chicken” (62) and pursue the unanswerables when even “Know Thyself can be a Medusa turn-to-stone blow” where the knowing might not turn out to be knowing at all (70). Such questions might ordinarily be the province of the philosophers, but in this book they are better explored in the aisles of a grocery store, sitting in the light of a window sorting pieces for a quilt, while waiting for a dental hygienist, in every ordinary ritualized passage through changing seasons—all ways of measuring the extraordinary in ordinary places and moments to “explain the familiar so that I might understand” (102).

From section to section and within each poem, we are treated to intricate patterns of repetition found in everyday experiences. Some are like the musical refrains of the oral tradition or the contrapuntal wizardry of Bach; others use variations and inversions to capture multiple perspectives or introduce the rhythms of the blues. Smallwood is a master of forms whether it is villanelles floating variations that coalesce in a concluding couplet, the expected but still surprising repeated endwords of her sestinas, or lines sewed together seamlessly through successive stanzas where beginnings and conclusions meet in pantoums. The masterful wedding of mundane experiences and heightened awareness is found in “A Kroger Villanelle,” where a regal-feeling shopper passes in review objects on shelves “lined at attention,” her wobbling crown cautioning deliberateness in her step. As the shopping cart swerves through each aisle six times “she nodded and smiled” (110).

Live with this book for a while, quietly and thoughtfully, and you will be dazzled by seeing things as if for the first time. It will come over you, for example, that so much of what we assume has been decided opens up again because of “mystery in the measuring” (“One Way,” 25). You will notice the worn-out elastic, the “almost invisible 3-corner tear,” and how a white apron “must’ve gotten untied” in “Raggedy Ann” (41). Of course we like measurements assumed to be exact and indisputable, sometimes even declared true by definition. But do we truly know for sure what day we are living in with the help of a calendar, a dated email message, when the garbage is picked up, or an electronic sign on a bank? And how do we determine which metric might have gotten it wrong or—when they conflict, how to decide on accuracy (“Proof,”44)? Quilt making is all about measuring: selecting, cutting, matching, planning for counterpoint, storing memories. Can the drive to measure go too far; do quilts have to have purpose and be made to live with certain people, or after we are gone will their final measurement be “ending up in the night pyre” (“Sewing by Day,” 46). As part of elevator talk about how busy we all are, a clerk responds “it is what it is.” Floating somewhere between cliché and profound truth is a distance hard to measure where we don’t know what is what or the meaning of either “is” (“What Does it Mean,”51). Do we quantify maybe overmuch sometimes as when a customer wonders “how many sperms died not reaching the egg” that formed the cashier who was a “Fred Astaire with bills” (“Sorters and Watchers” 69). All the measuring in the world brings us back to a wholeness; we avoid overreliance on measured analysis by learning that “it’s wise to detect differences in what seems the same” (Seeing the Whole.” 95).

In the Measuring will remind you of the strengths and limitations of every device we use to capture lived experience. Smallwood is at home in a wide variety of forms and styles. She is meticulous about modifying forms for special uses, and matches them unobtrusively to content they were made for. The organization of the book will serve as a guide but never get in the way or overcomplicate. Cover and interior design by Shanti Arts Designs are gorgeous reminders of the process explored everywhere in the book. Layout, design, font, and spacing are pleasing, with plenty of white space for readers who annotate as they read. In a few places really short poems positioned at the top of a page might seem abrupt to some. I would have liked a few more glimpses of the author’s ways of composing or motivations for the project in an overly short but otherwise effective Introduction. The Foreword by Foster Neill, founder of The Michigan Poet, welcomes us to ways of enjoying the surprises in the wisdom a keen poet has created for us.

About the reviewer:

Ronald Primeau is Professor Emeritus at Central Michigan where he directed the Master of Arts in Humanities program. He is the author of many books on American literature. Books list, click here.

Recent Comments