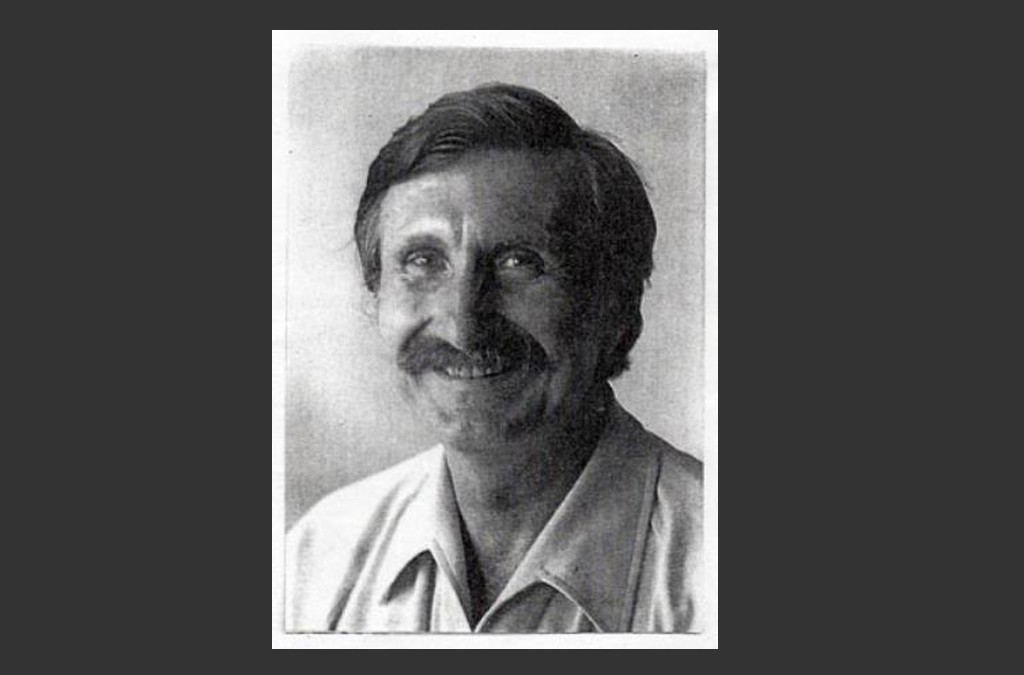

Nick Kolumban

**

“inside a Yankee coat…”

by Paul Sohar

Contributing Writer

There was a poetry reading in New Brunswick last June 14th to celebrate what would have been Nick Kolumban’s 78th birthday. Anne, his widow, was there, and his daughter Nichole with her husband Daniel and two children participated. Nicholas Kolumban (1937—2003) was born in Hungary and came to the US in the 1956 wave of refugees. After finishing his higher education he worked as a teacher of English and German. He published numerous volumes of poetry and had more than 150 magazine publications which earned him a NJ medal of honor as a poet.

Contrary to their traditional image, poets rarely have an outgoing, free-spirited personality; they usually express themselves in their poetry and not in their everyday interaction with other people. Nicholas Kolumban was an exception. Even while raising a family on a regular teaching job he reveled in the life style of spontaneity when the opportunity allowed. In spite of all my fitful efforts and sporadic publications, I was essentially a closet poet when I came to know him.

Baconsky, a Romanian poet, once observed that poets recognize one another by the same invisible signals by which thieves recognize one another. And then the game of uneven friendship and friendly rivalry begins.

That was exactly what happened when I met Nick – or Miklos, Miki, to his Hungarian friends – at a meeting of the Hungarian Alumni Association, a loosely organized cultural-political society on and around the Rutgers campus. He was already a poet of some note in NJ, often the invited poet at such popular venues as Micawber Bookstore in Princeton or the Rocky Hill Library, a real PUBLISHED poet and the darling of this social circle. Nick was basically a very serious man, but in his interactions he played the bohemian poet role to the hilt. Much of that was self-advertisement but it also served to feed his own ego besides his reputation. On learning that I too labored – part time – in the groves of literature he immediately gave me a hearty handshake and thud-like pat on the back calling me a fellow poet, a welcomed kindred spirit. At first his unquestioning acceptance of me as a fellow poet – even without seeing any of my stuff – seemed indeed heartwarming as well as promising an exciting artistic friendship. And even a way to revive my lagging literary career.

“Of course, my friend, of course,” he assured me with a great display of bonhomie. “Come to my reading this Saturday afternoon at the county college. There’s going to be open mic afterwards, and you can introduce yourself to the poetry community.”

He turned out to be one of the three invited readers, and they went on for close to two hours before an intermission. I sincerely congratulated him on his presentation; indeed I found his otherwise mainstream style poetry bore the hallmarks of his personality, every poem had quite a few genuinely poetic lines that made the whole piece worthwhile. I was eagerly looking forward to his reaction to the poems I was going to read; however, when the afternoon reading resumed with the open mic session the invited poets had disappeared along with a large part of the audience. I read two of my creations to a handful of other unpublished poets, all of them signed up for the open mic, who dutifully applauded my performance, but no one approached me or engaged me in a discussion of what we had heard, or about poetry in general, nor our own in particular.

“Join a workshop,” was Nick’s advice when I ran into him the next time at a lecture on the relationship between poetry and politics.

“You missed my reading at the open mic,” I reminded him, somewhat peevishly. “Would you care to see some of my stuff?”

“Oh, you know how these readings go,” he grinned at me from ear to ear as if about to reveal the secret of success in literate. “We always like to adjourn for a glass of beer in the intermission and then one thing leads to another, one round to ordering another, and time slips through our fingers before we know it…”

And then he went on telling me how much fun he had had later on that afternoon that stretched into the evening and the night in the company of other poets and artists, a real bunch of bohemians. When I pulled out an envelope from my pocket, stuffed with six or seven of my surrealist masterpieces, he looked at it as if I were serving him with summons to appear in court. I assured him it only contained my poems, he nodded in reluctant assent and stowed the wrinkled package in a thin paperback book he had in his hand. But then he changed his mind and shoved the book in my face.

“Good news!” he announced triumphantly as if we had been toasting with glasses of beer in an artists’ café in Soho instead of standing in a library conference room. “My new book is out! The official launch will be next week in Cedar Tavern, and you’re of course invited. But you can have an advance copy now at the wholesale price of ten dollars, saving you five dollars off the store price.”

I obediently handed over a ten-dollar bill, and he presented me with the book, signed, dated and dedicated to me as a fellow poet. Fellow poet! Imagine that. Maybe someone like those other PUBLISHED poets he was in the habit of drinking beer with. I was very impressed, but I reminded him that the envelope with my poems was still in the book.

“Yes, of course… Sorry, but my mind is so full of plans for this book and the launch… Writing a book is easy, but publishing it is a bitch… And selling it even more of a drag… Getting people to review your book…” he shook his head in mock dismay until suddenly his broad grin returned. “But where there’s a will there’s a way. Remember that. Every step of the publication process involves some shortcuts, innocent tricks, a little know-how. Take the review step. I’m already busy writing reviews of this new book of mine that I will send out under pennames. Using a penname – a nome-de-plume! – is a time-honored tradition, and who else knows more about the writing in question than the author? So why shouldn’t the author review his own book? Especially if his friends are so damned lazy and never come through with the promised review. I cannot get mad at them, of course, because I am the same way… Last year I had someone’s prepublication manuscript for months and months, he wanted a preface or at least a blurb, but I just couldn’t get around to it. Finally, when he called me the nth time about it, you know what I said? I said there had been a horrible accident in my basement study where I do all my writing and everything, and one night the cat peed on the manuscript. All I could do was apologize profusely for my cat’s unseemly behavior… How do you like this ingenious story? Don’t forget, the more unlikely and utterly impossible a story, the more believable. No one would resort to such an outrageous lie, that’s how people react. So if you have to tell a lie, make it big one, and you can be sure to get away with it.”

And that was the lesson of that particular poetry workshop. Nick was more generous with his spoken words than the written ones, and he always had time to spare, at least five-ten minutes to tutor me in the tricks of his trade. And he kept inviting me to every one of his readings as if it were an initiation rite for me in the art of poetry. And into the secret society of POETS. I faithfully followed his booming career, all the time waiting for him to get back to me about the poems I had given him to read and possibly recommend to a friendly magazine editor for publication. Waiting and waiting, not wanting to be pushy. But never a word from him about my stuff.

In the meantime a rather ambitious translation project came along, involving Transylvanian-Hungarian poetry. Gyogyver Harko, the editor of the anthology “Maradok – I Remain” chose me over Nick for the job, because I was willing to struggle with formal poetry and reproduce the form as well as the content in acceptable English. Nick didn’t seem to care, he no longer needed translation work as an entre into the literary world, he was already in it.

The anthology eventually materialized as a real book, and many of the translations in it later appeared in such A++ (by Nick’s rating) publications as Chelsea, Kenyon Review, Seneca Review, etc. etc. Suddenly Nick changed his tune and started treating me as his equal. It was only then that I finally queried him about the manuscript I had asked him to critique and possibly push for me.

“Oh, that!” he let out a great sigh with his arms raised in a theatrical gesture better suited for the role of King Lear. “I’ve been meaning to talk to you about that, but I just couldn’t. It was too embarrassing… You know what happened, my cat peed on your stuff in that envelope, and the whole thing became a mess. I hope you can forgive my cat for that awful accident…”

The bigger the lie, the more believable. I remembered the lesson, and I just nodded in generous exculpation of his cat. Reality is just another form of fantasy; how could I, a self-proclaimed surrealist disagree with that? Besides, that was Nick, what else could I expect from him? Well, for one thing I would have expected at least a new story, a new lie to sooth my wounded ego. But he made up for the slight by offering me more useful advice.

“Yes, of course, you need more publication credits in your bio, but what’s to prevent you from being more creative about it? Just make up a title for a poetry book you supposedly published way back, let’s say in the ’60s, in pre-internet times, and no one’s going to check on it… And the publisher? Call it something unexpected… like the Purple Polar Bear Press… or the Bipolar Bear Press…”

That was how my volume of poetry “In Sun’s Shadow” was born, but Ms. Harko was horrified when she saw it in my bio at a presentation of our anthology. It was no use me citing Nick as the inspiration for the innocent ruse; “In Sun’s Shadow” had to go.

But Nick’s overall career as a poet was no lie, it was real. It’s too bad it was cut short by a tumor growing slowly but inexorably deep inside his brain. He bore the incurable illness with stoic acceptance, sometimes even joked about it with gallows humor, but sometimes he shared his despair with me. I used a Y pool near his house and often stopped by his place in the late afternoon for an aperitif and chat, a sip of Jamaican rum or Mexican beer, sitting in the kitchen. In those last two years he started to write in Hungarian again, and I think those poems were his best. He had always lived life to the fullest and celebrated it in his poetry, but when time threatened to run out, his awareness of every passing moment seemed to intensify even more. Except for forgetting names and numbers, his mind remained lucid till the end, and he went out of this life as a good poet and a loving soul. And an unforgettable character.

See also:

Recent Comments