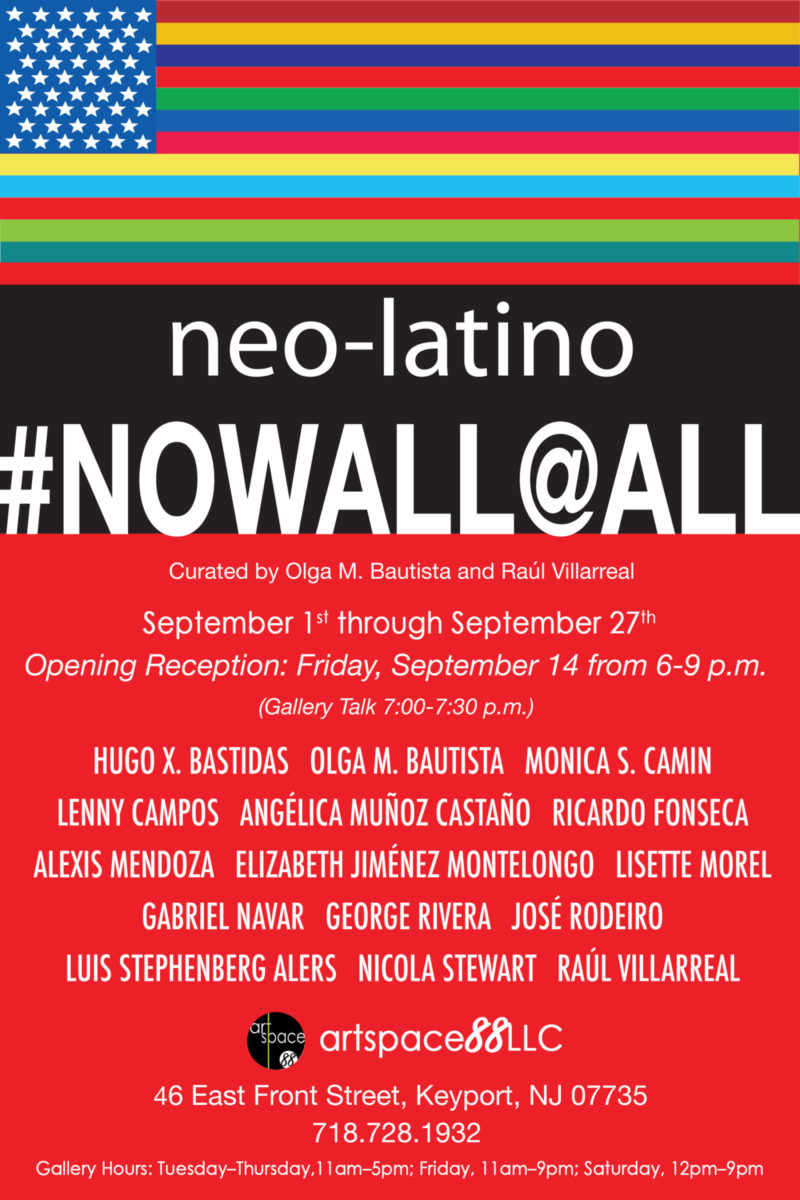

NEO-LATINO#NOWALL@ALL

Neo-Latino Artists exhibit at ArtSpace 88 Gallery

by José Rodeiro

O

n the eve of National Hispanic Heritage month, celebrating US-Latino culture and ethnicity, Art Space 88 Gallery in Keyport, New Jersey, presents the Neo-Latino Artists’ Collective’s exhibition titled Neo-Latinos: #NOWALL@ALL. The show runs from September 1–27 (2018) with an artists’ reception (free and open to the public) on Friday, September 14 from 6-9 p.m., together with a gallery talk from 7:00-7:30 p.m.

The show’s co-curators, Olga M. Bautista and Raúl Villarreal, selected 15 Neo-Latino artists who hail from the Pacific to the Atlantic, mandating visual art that thematically addresses the current US-administration’s proposed Southwest border wall. The responding artists include Hugo X. Bastidas, Olga Mercedes Bautista, Monica S. Camin, Ricardo Fonseca, Elizabeth Jiménez Montelongo, Alexis Mendoza, Lisette Morel, Angelica Munoz Castano, Gabriel Navar, George Rivera, José Rodeiro, Luis Stephenberg Alers, Nicola Stewart, Raúl Villarreal, and ‘invited-artist’ Lenny Campos. The selected exhibitors represent a broad swathe of Ibero-American heritages, including Argentina, Colombia, Cuba, Ecuador, Dominican Republic, Mexico, Portugal and Puerto Rico. Villarreal named the group in 2003. Thus, art historically, Neo-Latinoism is the first and longest-lasting national art movement of the twenty-first century.

The show’s co-curators, Olga M. Bautista and Raúl Villarreal, selected 15 Neo-Latino artists who hail from the Pacific to the Atlantic, mandating visual art that thematically addresses the current US-administration’s proposed Southwest border wall. The responding artists include Hugo X. Bastidas, Olga Mercedes Bautista, Monica S. Camin, Ricardo Fonseca, Elizabeth Jiménez Montelongo, Alexis Mendoza, Lisette Morel, Angelica Munoz Castano, Gabriel Navar, George Rivera, José Rodeiro, Luis Stephenberg Alers, Nicola Stewart, Raúl Villarreal, and ‘invited-artist’ Lenny Campos. The selected exhibitors represent a broad swathe of Ibero-American heritages, including Argentina, Colombia, Cuba, Ecuador, Dominican Republic, Mexico, Portugal and Puerto Rico. Villarreal named the group in 2003. Thus, art historically, Neo-Latinoism is the first and longest-lasting national art movement of the twenty-first century.

The exhibition examines the current US administration’s proposed Southwest border wall, extending 2,000 miles from San Diego, California, to Galveston, Texas, in addition to stretching far beyond the shoreline on both coasts. Hence, Art Space 88 Gallery’s show “Neo-Latinos: #NOWALL@ALL” conceptualizes, evokes, and conjures artistic imagery about this monstrosity that is estimated to cost $25 billion or more (shouldered by U.S. taxpayers), along with projected annual security, repair, and maintenance outlays in the hundreds of millions of dollars. Grimly, around three-fifths of the proposed “Wall” parallels the Rio Grande River, and by building north of the river, it could greatly hamper Texas’s access to freshwater, thereby ceding millions of barrels of Rio Grande’s water to Mexico to the detriment of American farmers and ranchers.

Additionally, from the Pacific Ocean to the Gulf of Mexico, “The Wall” would impede hundreds of animal species’ annual migrations, resulting in thousands of creatures perishing as they bravely try to circumvent continuous barriers, likewise quadrupling monthly death-rates among illegal Ibero-American immigrants (mostly from Central America), fleeing injustice(s), persecution, cruelty, and dire conditions in their nations of origin. Furthermore, “The Wall” would divide many border-towns, i.e., Campo, and San Ysidro, California; Rio Bravo, New Mexico; Lukeville, Arizona, and Laredo and El Paso, Texas, and others. Beyond the above-listed misgivings, The Wall would fiscally harm the U.S. economy, encumber trade with Mexico and Latin America, and cost millions to maintain — money that could be better utilized elsewhere.

A Glimpse at Some Images from Neo-Latinos: #NOWALL@ALL Exhibition:

Hugo X. Bastidas’s Boundaries, the Dividing Line, (Oil on linen, 38” x 56,” 1998) examines exactly what delineates national borders.

Painted during the Bosnian Serbian War in the Balkans, Bastidas sees clear parallels with current US policies, concerning the extant Southwestern border crises, concerning immigration, refugee-status, family separation(s), zero-tolerance, including what determines geographical border-lines, demarcating boundaries between nations, cultures, people, etc.; signifying in the Southwest an ambiguous border-line destined to evolve into a massive wall, which, as depicted in Bastidas’s painting, would need to be built upon miles of rocky-craggy terrain topographically unsuited for wall-building. As Bastidas explains, “The line in the painting is done flat over a scene, which creates an illusion of depth.”

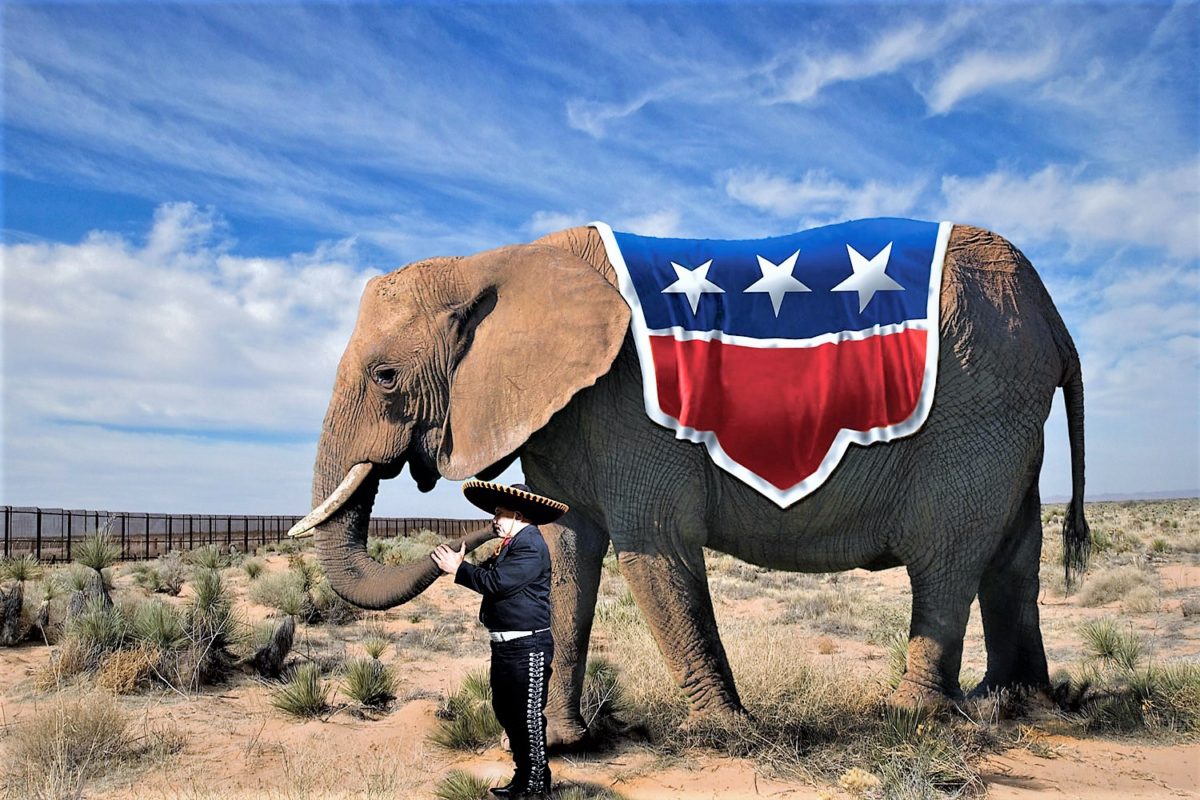

Ricardo Fonseca’s Trumpet (Digital Photographic Manipulation, 24” x 36,” 2016) alludes to The Book of Joshua’s account (6:20) of the demolition of the walls of Jericho by Joshua’s trumpet blast, affording Fonseca a pun on “Trump’s” name. In the piece, a Mariachi musician confidently stands, assuming the role of Joshua as he blows into the trunk of Thomas Nast’s symbol of the GOP: the Republican Party elephant adorned with a colorful cloak, sporting the tri-colors of the Russian flag.

As a child in Portugal, Fonseca noticed landscapes overlain with medieval walls, marking each castle’s domain, crumbling reminders of a lost Amnesis lacunae. Fonseca questions the viability of such a puerile medieval world-view in the Twenty-First Century, stating, “In our present day, there are strong forces (globalization, technology, transculturalism, and ecumenicalism), which skew such irrational or antique views that rim our understanding of mutable boundaries. My artwork spotlights those questionable forces. At some point, we have to ask who is playing whom? And more importantly, what is the trumpet sound being played, and what is the sound being heard: sublime music or just noise?”

Monica S. Camin’s The Book of Life (Oil on canvas with mixed media 31” x 50,” 2018) examines myriad interconnections, contextually linking each human being’s unique personal history to world history. Yet, as we journey through life, despite crisscrossing numerous seemingly impersonal landscapes marked by arbitrary invisible cartographical lines, Camin realizes how deeply intertwined our individual history fits into world history. In her painting The Book of Life, each person is “mapped-out” in black-&-white, forming geographies comprised of shamanic duende-filled beings, exalting their individual Whitmanesque “self-nationhood,” thereby fully embodying Emma Lazarus’s eternal American Dream exemplified by a person’s deep longing for ‘Freedom’ nourished by a free-press, democracy, open elections and blind justice. Herein, Camin astutely affirms that immigrants, refugees, borders, nationality, ethnicity, and identity are all innately human conditions. Thus, by abstractly depicting people as black-&-white emblems of our interlaced humanity, she questions what forms of mental limitation, within malicious authoritarian individuals throughout history, always compels them to stoke fear, hatred, and cruelty against fellow human beings in order to obstruct ‘Freedom?’

Olga Mercedes Bautista’s Bonding with Plastic (Installation piece, silicon, leaves and plastic debris, a picture frame with an image of shoreline detritus. 6′ x 10′ x 11,’ 2018) decries the current U.S. government’s inability to acknowledge climate change, evident by the USA’s irresponsible departure from The Paris Accord, permitting the current Environmental Protection Agency and Department of the Interior to deliberately not protect air, soil, water, and endangered species, which Bautista imminently perceives as being harmful to life, health, and well-being.

In her installation, she exposes the connection between our economic over-reliance on harmful plastics as a concomitant part of contemporary post-industrial merchandising (packaging), consumerism, and materialism. Her intention (in her work) is to reorient and transform plastic into something properly recycled as something aesthetic, agreeable, accommodating, and reusable.

Alexis Mendoza’s abstract-painting series titled Taking Down All Border Crossings offers perceptive images such as his alluring red and blue horizontal piece (mixed-media on found-wood, 2018), which echoes French philosopher Michel Foucault’s world-shattering social theories aimed at achieving absolute freedom, including the elimination of all border-barriers, calling for the dismantling of all walls, fences, and geographical limits. As Mendoza maintains, “Boundaries are something that for years people have been trying to eliminate, because of their negative impact on actual people who live in communities and countries where so called ‘border crossings’ have been built by government officials.” Mendoza’s series represents a creative-project that he has developed over the last two years, advocating the destruction of all border crossings and barriers around the world and subsequently recycling all the materials collected from these barriers into works of art, e.g., like those built throughout the world using pieces of the Berlin Wall. In fact, Mendoza’s works are often created with detritus from actual border-crossings, fence-materials, and boundary-walls furtively sent to him via his world-wide network of artistic collaborators.

Raúl Villarreal’s “Yeah, yeah, I’ma go into this” (Oil on canvas, 40” x 30,” 2018) appropriates from Francisco Goya’s poignant duendesque Black Painting Saturn (Cronus) Devouring His Son (1819-1823), where the Titan of “Time” chomps on his son Poseidon, after previously eating his other children (Hestia, Demeter, Hera, and Hades) to prevent them from supplanting his divine authority (“his power”). For Villarreal, Goya’s image exemplifies the USA’s feckless relationship with the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico from 1898 until the present. In the piece, we witness a vicious cannibalistic infanticide perpetrated by a monstrous colossus, who is driven mad by fear of usurpation.

As the Latino population and other minority populations in the United States grow, some insecure members of society seemingly fear losing their strong hold on political and financial power. From The Jones Act, to Vieques, to handling the aftermath of hurricanes Maria and Irma on the island, the USA’s treatment of its own “children” is nothing short of disgraceful and marked by disparate response(s) regarding hurricane relief — instantly helping Texas & Florida, while slighting Puerto Rico and The Virgin Islands for ten months. The two storms, Irma and Maria, initially were said to have killed around 1,400 U.S. citizens; the body count has gone up since the initial estimates were released. Moreover, due to The Federal Emergency Management Administration’s inadequate and incompetent response to the disasters, many regions of those areas went ten months with inadequate access to water, medicine, food, and electricity. And, as the death-toll rose, according to Omarosa Manigault Newman’s account in her book Unhinged, Trump joked about Caribbean suffering and pain, while intentionally refusing to act with urgency.

José Rodeiro’s “You Knew Damn Well” (Oil-on-canvas, 16”x 20”, 2018) derives its iconology from the lyrics of the Rhythm-&-Blues song “The Snake” by Oscar Brown (1963). The image depicts a grassy knoll along the ridge of Border Field State Park overlooking the shores of Imperial Beach, California, USA, whereupon a Latina immigrant dies from a snake-bite. The melancholic image revolves around Brown’s “The Snake,” which was musically rearranged into a hit song by Al Wilson (1968); the poem originally derives from Aesop’s Fable “The Farmer & the Viper.” Rodeiro’s painting owes a great deal to Edgar Allen Poe’s theory of melancholic beauty in art, i.e., symbolically camouflaging within the snakes’ scales distressing words. Additionally, as a parable justifying the need for “The Wall,” throughout 2016’s presidential campaign, the lyrics were often recited by Donald Trump at rallies.

Gabriel Navar’s “tweetering wall hate” (acrylic, pencils, ink & oil on Masonite, 18” x 24”; © G Navar, 2018) illustrates the idea that an ill-informed, uninquisitive person might foolishly believe the urban myth that America’s greatest psychologist B.F. Skinner in 1943 actually placed his second infant daughter in a box at birth in order to conduct a behavioral experiment to see what would occur if a baby spent her first years of life isolated from human contact. Of course, none of this is true; instead, Skinner designed a “boxy” apparatus called the “aircrib baby-tender” to help his wife attend to his second daughter. Gloomily, Navar’s image presupposes the former view that a poorly educated yellow-haired mad behavioral socio-psychologist in a Russian-blue scientific lab-coat searches with binoculars for young Latino children along the stark Southwestern border wall. Instead he finds two cherubs from the lower section of Raphael’s painting of The Sistine Madonna. As an experiment, the demented yellow-haired scientist wants to cure Latino children of dreaming “The American Dream,” by tyrannically placing them at 8-weeks of age to 5-years of age, all the way to teenagers, within hard cold wire cages, sleeping on Mylar(tm) blankets on hard, cold, unclean floors. More than 3,000 children were separated from families for months, unloved, ignored, untouched, uncleaned, mistreated … and even now more than 500 remain either abandoned or misplaced.

Additionally, Neo-Latinos: #NOWALL@ALL presents outstanding works manifesting every aspect of contemporary visual art, i.e., powerful visual imagery by Dr. George Rivera, an outstanding practitioner of video art, digital art, and installation; sublimely intimate photographs by Angelica Munoz Castano; provocative conceptual sculptures by Nicola Stewart; brilliant conceptual mixed-media works by Luis Stephenberg Alers (an extraordinary artist involved in installation, video-art, and performance art); and, a duende-filled virtuoso abstract “painterly” installation by Lisette Morel. The exhibition is graced by Elizabeth Jimenez Montelongo’s ingenious, magical, and folkloric imagery. Plus, the unique images of special guest artist Lenny Campos.

In 1963, during his Berlin Wall Speech, a visionary U.S. President named John F. Kennedy elucidated, “Freedom has many difficulties and democracy is not perfect. But we have never had to put a wall up.” This idea was reaffirmed in 1987 by President Ronald Reagan, during his Berlin Speech, declaring, “Mr. Gorbachev, tear down this wall!” Or, Senator John McCain’s final warning from his death bed (2018) to the American people, “We weaken America when we hide behind walls, rather than tear them down.”

Neo-Latinos: #NOWALL@ALL can be seen at ArtSpace 88 Gallery, 46 East Front Street, Keyport, NJ 07735. Tel. 718.728.1932. Gallery Hours: Tuesday-Thursday 11 AM–5 PM / Friday 11 AM–9 PM / Saturday 12 PM–9 PM.

Recent Comments