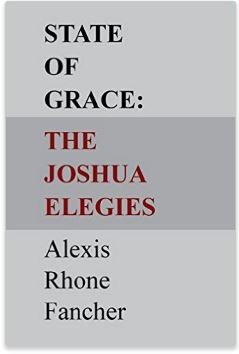

State of Grace:

The Joshua Elegies

by Alexis Rhone Fancher

Published by KYSO Flash Press, 2015

ISBN 978-0-98-627032-1

52 pages

$20.00

“…not an abstract metaphor.”

Review by Paul Sohar

Death is a ready-made dramatic situation; the word alone carries a heavy emotional weight and it is often used as a metaphor for the capricious and irrational aspect of life. However, Alexis Rhone Fancher was not looking for a metaphor when she set out to write her collection of poems State of Grace : The Joshua Elegies; death forced itself on her consciousness when her son died at an early age of twenty six, at a time when an adult life is supposed to take shape, standing on the threshold of hopes and ambitions coming true. Death hit the sensitive soul of this poet with all its cold reality, sometimes paralyzing her emotionally to such extent that her life became a series of irresistible crying spells. Her only defense against the cruel twist of fate was to write about it, to write about death as it affected her and not as an abstract metaphor. The resulting poems touch upon all the features of true grief, the self-blame, the sudden void caused by the departure of a loved one, and the search for a meaning, and they inevitably find expression in confessional style, in narrative free verse that verges on prose poetry, some seem like diary entries and yet some soar into the tone of true poetry. The best example of poetic and yet very sincere expression of her grief is

“When You Think You’re Ready to Pack Up Your Grief“:

Begin with his letterman’s jacket.

Bundle it together with regret.

….

Don’t tuck his senior portrait in the side pocket.

Lay it beside delicate items,

like feelings, face down;

place tissue paper on top.

…..

When friends ask to help, don’t

spread the grief around. Keep it for yourself.

When the suitcase won’t close, don’t sit on it.

Don’t even try to shut it.

Notice the line break between the first on the second lines of this last stanza: she says don’t but then stops the line there and starts the next line with the affirmative spread the grief around. Obviously, she needs to do both. She shows the same ambivalence about the meaning of the tragedy. How could this happen to a boy who was so full of life, so active in basketball and in love with powerful cars? She knows there’s no meaning and yet she keeps probing; better that than letting emotions throw her into a deep depression and losing her own life.

Only the closing poem of this selection reaches for even higher artistic spheres:

“when her son is dead seven years”

3.

a woman is skating barefoot on her sorrow,

her brain awash in the smell of his skin,

her arms shackled to the stars , a

pirouette of unmet promises,

regret, if she blames it on herself

she can fix it.

Perhaps she needed the separation of seven years before she could mount a truly memorable monument to the son she lost to cancer. Her more immediate reaction to the loss was too overpowering to yield to such treatment; the feelings were too raw at that point and she could only cry out in helpless agony or sometimes in fury at other people who could not understand her state of mind and said only inanities in their effort to express their condolences. But at that point no condolence was possible for her except in the words prompted by her pain; losing a child at any age is like losing part of one’s life.

Apart from a few anecdotal poems that mar the somber spirit of this small collection with their chitchat tone (e.g.: “Death Warrant”), this book will stand not only as Fancher’s memorial to her son’s memory but as an ageless addition to the poetry of mourning.

About the reviewer:

A frequent contributor to Ragazine, Paul Sohar ended his higher education with a BA in philosophy and took a day job in a research lab while writing in every genre and publishing seven volumes of translations. His book, “Homing Poems”, is available from Iniquity Press. Recent translation credits include a recent book of poems by the renowned Hungarian poet Sándor Kányádi as well as poems by US poets for Hungary’s elite literary publication Magyar Naplo. He gives poetry readings throughout the United States and Europe.

A frequent contributor to Ragazine, Paul Sohar ended his higher education with a BA in philosophy and took a day job in a research lab while writing in every genre and publishing seven volumes of translations. His book, “Homing Poems”, is available from Iniquity Press. Recent translation credits include a recent book of poems by the renowned Hungarian poet Sándor Kányádi as well as poems by US poets for Hungary’s elite literary publication Magyar Naplo. He gives poetry readings throughout the United States and Europe.

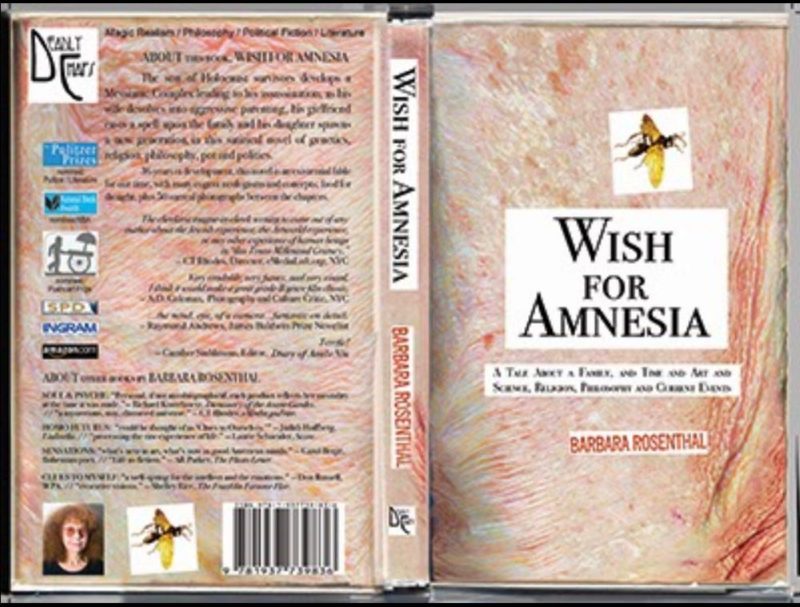

Wish For Amnesia

by Barbara Rosenthal

Deadly Chaps Press, 2016

ISBN 978-1-937739-83-6

Pages 285, Price: $20.00

Wish For Amnesia:

So much for the Age of Aquarius

Review by Mike Foldes

Barbara Rosenthal sent me an early copy of this book, which I started to read and then put down when she wrote, “Oh, that’s not the right copy… I’m still working on another draft. Wait for that one before you read it.” So I did, fearing that it might be some time before she finished since she’d begun writing it more than 35 years earlier.

A year or so later I was relieved to receive the “final final” draft Published version — so I would have to wait no longer. While I don’t know what she changed, it would surprise me not at all to discover the changes were many and had as much to do with handling the bulk minutiae that make this book an adventure in language, as well as an entertaining “Siddhartha-type” read. The leaps of faith are many, and while a few of those leaps are longer than some readers will go, there are both pleasant and disturbing surprises in store for those who do.

Briefly, the story revolves around four main characters, three of whom come of age in the ‘60s sub-culture dominated by sex, drugs and mysticism. The fourth being Jewel, the offspring of Caroline and Jack, who were introduced, and to some extent managed, by the third, Beatrice, a somewhat older, blind artist whose ability to “see” far surpasses the literal physiological meaning of the word.

This is not an easy book to slide into; you may have to work some to get into the rhythm of things and wonder whether you really need to know that “Scientia” is on the left and “Ars” on the right at the gate to Columbia University, but these are the kinds of things that pass through the minds of Rosenthal and her characters, and in doing so become over-coated with peripheral value:

“We are nearing the end of the Ages of Culture,” he said, casually smiling to the small, privileged, inner group still dogging his steps, and he stopped to list as they occurred to him: “Age of Earth, Age of Order, Age of Esthetics, Age of Mechanics, Age of Biophysics, Age of Astrogenetics.”

He laughed out loud. For each age a geodesic paperstraw star was imagined. He couldn’t get this walk done fast enough.

Jack, an anti-establishmentarian by any standard, nevertheless achieves a level of recognition placing him in the higher echelon of diplomacy with a position at the United Nations. By the end of the book, in a nod to the Peter Principle, Jack reaches his natural level of incompetence.

His wife, Caroline, embodies ennui and emotional detachment exemplified by ‘50s and ‘60s stereotypes of housewives with successful husbands, including those with children, who find themselves at a loss simply being who they are. Caroline often wonders how she got where she is, turning to self-administered drug therapy, as if it would pave the path to understanding. She occasionally draws in an old “friend” whom she considers inferior, simply to make herself feel better despite the friend’s fragilities.

One might say Beatrice mirrors the Cliff Notes’ explanation of the character by that name in Shakespeare’s “Much Ado About Nothing”: She is likely to touch a responsive chord with many readers and playgoers today in light of current social ideas that encourage greater equality and self-assertiveness for women than has been traditional for women of the Western world. The traditional woman of the Elizabethan period, especially of Beatrice’s class, is better represented by her cousin Hero — the naive, chaste, and quiet young woman of whom Beatrice is extremely protective. Beatrice is as cunning and forward as Hero is naive and shy.

Their precocious daughter Jewel, suffers the consequences of a physically absentee father, and an emotionally absentee mother. Of her family, she writes;

This is what my family thinks about time:

1) Caroline: The present is an imaginary location between past and future.

2) Jack: The present is a time of action produced by the (real) past and undertaken on behalf of the (ideal) future.

3) Beatrice: Past and future are only aspects of the present.

The surreality of the drama unfolds over a period stretching from WWII on a train to Auschwitz, to the end of the 20th Century, from Europe to North America and back again – this time to Italy — where Beatrice undergoes a magical recovery of sight in a denouement that brings the story full circle.

The book is a kaleidoscope of references to obscure and eclectic subjects evinced by Jewel, the self-indulgent Caroline, the in-over-his-head Jack, and the evil godmother Beatrice. As such, they are delightful to experience, especially since most are explained in one way or another saving the reader a trip to her Oxford dictionary or Britannica encyclopedia, or (more likely these days) his run to a computer to fact check with Google or Wikipedia.

But the story really is about Jewel, whose search for love and meaning is indebted to J.D Salinger, Christiaan Huygens, Isaac Newton, Herman Hesse, Jean Giradoux, Albert Camus, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Richard Farina, and others too numerous to mention. You get the idea. I, for one, thank Joseph Quintela for publishing “Wish For Amnesia,” and I believe many other readers will, too.

About the reviewer:

Mike Foldes is founder and managing editor of Ragazine.CC. You can read more about him in About Us.

Nice breakdown of this Pynchonesque, picaresque, sci-fi gospel parable.