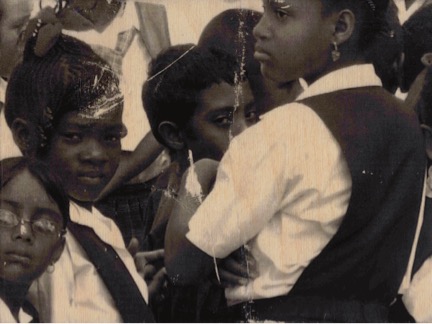

Photo by Dan Luedert, 2004

Me with my student Jade at Vryman’s Erven Secondary School, New Amsterdam, Guyana.

***

Un | Fixed Homeland:

How Art makes me want to be a Guyana Girl again

by Celeste Hamilton Dennis

Before I left for Peace Corps Guyana in 2003, my father would sit me down and show me printouts from the Internet of the covers of various Guyanese newspapers from the previous couple of years. The thread between them all was the same: bloodied faces of bandits from the gang-ridden town of Buxton, a village I’d inevitably have to pass through anytime I would need to go the capital city of Georgetown.

“Are you sure you want to do this?” he’d say.

I’d nod. I was 23 years old, idealistic about the world and my contribution to it. Nobody, especially my father, was going to stop me.

Thirteen years later, I find myself at Aljira, a Center for Contemporary Art for the opening of Un | Fixed Homeland, an exhibition featuring thirteen contemporary Guyanese artists examining homeland via photograph and photography-based art. It is curated by the Guyanese-born Grace Aneiza Ali who migrated to the United States when she was 14 years old.

One of its central pieces is “Mother’s House with Beware of the Dog” by Frank Bowling. A mixed media painting, it’s fashioned after a vintage photo of his mother standing in front of their general store on Main Street in New Amsterdam, Guyana.

Installation shot of Frank Bowling’s “Mother’s House With Beware of the Dog,” 1966.

(All installation images copyright of Aljira, a Center for Contemporary Art.

Photography: Argenis Apolinario)

On the wall text next to the painting he is quoted: “New Amsterdam is the most important place, and it reappears all the time…in my quiet moments it reappears. It was a town that was full of terror, and at the same time it was marvelous..it belonged to me.”

I read these words and nod. I feel exactly the same.

Bowling, an 80-year-old Guyanese man of African descent, is an internationally renowned abstract expressionist with a career that has spanned over five decades. I wonder what he would think if he knew that me, a 36-year-old white woman from Long Island, was standing here in front of his art and commiserating like I had any idea what he was talking about.

I would tell Bowling that New Amsterdam, a coastal town in the Berbice region and home to the only mental institution in the country, was where I spent more than two years of my life with the Peace Corps in my early 20’s as a high school reading teacher.

I would also tell him that I’ve walked down Main Street countless times to shop for a tawa to make roti on or to exchange my U.S. dollars for Guyanese ones. It was a street where a call of “Miss Celex!” accompanied by a wave from my students was part of my daily routine.

My students at Vryman’s Erven Secondary School,

New Amsterdam, Guyana. Photo by Dan Luedert, 2004.

A mash-up of different ethnicities whose name translates to “land of many waters,” Guyana is Caribbean in culture, more similar to its Trinidadian neighbor up north than the countries it shares land with. Its history is one of movement and displacement of various peoples: African slaves, Chinese and Portuguese immigrants, native Amerindians, colonial Europeans, and indentured servants from India. And the movement continues today — more Guyanese live outside its borders than inside them.

Before this, however, I knew very little about Guyana and what I did know was filtered through a Western gaze like my father’s. I knew it was where the Jonestown massacre of 1978 occurred. I knew it was in South America and a former British colony. I knew that whenever I told people where I was going they’d remarked that I needed to be safe in Africa.

I arrived in Georgetown and was immediately shaken out of my comfort zone. Mosquitoes tore up my legs so much so that the locals thought I’d been cursed. I could hardly understand a word of Creole. And I was scrutinized at every turn. People frequently offered me cream to rid the freckles (or rust) on my skin, I was scolded by older Guyanese women who thought my skirts too short, and later in New Amsterdam, I had my ice cream habits reported at school. In an early letter to one friend, I’d told him that most likely I’d be coming home.

After a couple of months, however, the divide lessened and locals who went by names like Reds and Uncle Bird and Ras Brooks began inviting me to backdam liming, Hindu celebrations, and weddings of all kinds from African kwes kwes to Muslim ceremonies. Over the course of those two years, I fell in love.

Craig and I at Mashramani, an annual festival celebrating

Guyana’s Republic Day, on the calypso singer Slingshot’s

float during the parade in Georgetown in 2004.

In the most literal sense, Guyana was where I met my future husband Craig, a fellow volunteer in New Amsterdam, with whom I now have two children. We fell for each other under mosquito nets listening to the heavy rain and hanging out at the Chinese restaurants drinking Banks beer and telling stories of our past to entertain us during blackouts.

The other kind of love was more sneaky and gradual.

Even though I was craving the material comforts of America by the time I was about to leave my adopted home, I was heartbroken. My life would be absent of everything I never knew I needed to feel awake to the world: rum-soaked nights dancing to chutney and soca under stilted houses, hours spent listening to folklore stories about obeah, baccoo, and Anansi, time in the kitchen with aunties teaching me how to cook saltfish and bake, generous laughter with my neighbor Ceylon and other students whom I adored, and karaoke with ladies who belted out Beyonce as if they were the Queen themselves.

It was a time before social media ruled the world, and one where Peace Corps didn’t yet allow blogs. I was lucky that my time in Guyana was hardly interrupted with the click of a camera. I was unlucky in that, save for a handful of photos, I now need to rely on my faulty memory to relive a time in my life that thirteen years later, I am still constantly trying to recreate wherever I travel.

Installation shot of Erika DeFreitas’ “The Impossible Speech Act,” 2007.

(All installation images copyright of Aljira, a Center for Contemporary Art.

Photography: Argenis Apolinario)

Un | Fixed Homeland is an exhibition that allows me to indulge these memories I’ve tucked away, to piece together images of a country that is often overlooked on the world stage. It is a show that stubbornly refuses to let Guyana remain invisible and explores the complexities of a place that often is only associated with mass suicide or a maybe star cricket player, nothing more – even though it had a woman president long before the United States even considered it.

Through the lenses of the artists who come from both Guyana and the diaspora, Ali’s motivation behind the show is clear: while problems exist, beauty perseveres.

I’m embarrassed to admit I had no idea there were so many modern Guyanese artists. My only introduction was Claude Stevens, an aging man with cataracts who’d stand in front of the Demico eatery everyday, canvases of local rivers and bridges painted from his memory in hand. In my naive filter, I imagined him as a lone artist fighting poverty to make art for art’s sake, instead of what he was really trying to do, which was survive. I bought three of his paintings and they still hang in my house today, his memories shaking mine.

I didn’t even know there was an art school in Georgetown. And I hadn’t thought about a Guyana art scene until now, when I find myself working alongside Ali at the digital arts activism publication OF NOTE Magazine. She came to me last year in an unexpected moment of transition in my professional life, and I jumped at the chance to return to Guyana in any way possible.

Because Ali knows the American immigrant experience intimately, it’s fitting that the theme that connects Un | Fixed Homeland’s thirteen artists— from Brooklyn-based Kwesi Abbensetts to Erika DeFreitas in Toronto to Georgetown’s Khadija Benn—is migration. Via the work of these artists, Ali has weaved a narrative from the other side, exploring all the complexity, longing, and heartbreak that comes with leaving one homeland for another, as well as the stories of those left behind. On Aljira’s walls, their experiences are validated and most importantly, seen.

Installation shot of Sandra Brewster’s series Place in Reflection, 2016.

(All installation images copyright of Aljira, a Center for Contemporary Art.

Photography: Argenis Apolinario)

In their work, there are echoes of people I’d once known in Guyana in every frame. Looking at the Toronto-based artist Sandra Brewster’s “Guyana Girl 2,” a black and white photo transferred to wood of schoolgirls in uniform, I’m reminded of my students at the high school where I taught. When I would ask them what they wanted to be when they grew up, most of them had variations of the same response: “Miss, I want to go outside.”

Sandra Brewster’s “Guyana Girl” from the series

Place in Reflection, 2016. Courtesy of the artist.

Outside, a magical land where their aunties and grandmothers and fathers traveled to on a plane only to rarely return. Outside, the zip code where their barrels full of clothing and housewares came from. Outside, the return address on the Western Union transfers their parents received. Outside, which usually meant New York, Toronto, London.

Craig and I watch Los Angeles-based Maya Mackrandilal’s Kal/Pani, a video installation whose title references the blackwater creeks found throughout Guyana, and think of our friend Mr. Reece, a man of great character who could a climb a coconut tree as deftly as he could argue that teachers be paid their fair wages. It was with him we took a trip down the Berbice River and learned how to hunt wild boar. A few years later, he too moved “outside” to Philadelphia and began working as a stocker at Walmart so his daughter could live out her dream of becoming an engineer and his son, a doctor.

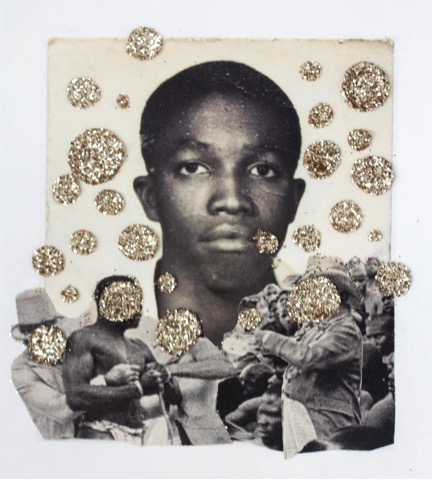

I view New York-based Keisha Scarville’s Passport series, passport photos of her father as a young boy rendered with everything from polka dots to lipstick, and recall my host mom Vanessa in the village of Mocha when I first arrived. As she packed my okra and pumpkin curry lunch everyday for training, she’d tell me about how, for years, her husband in the U.S. had been in the process of fetching for her and her daughter. Just now, she’d tell me. Just now.

Detail from Keisha Scarville’s series,

“Passport,” 2012-2016. Courtesy of the artist.

Peace Corps told me to keep my passport hidden. It was a thing most coveted in Guyana, its golden engraved seal a guaranteed ticket to the outside. I spent those two years safe with the knowledge that if things got rough or I got sick, I could leave. I could see my family if I wanted to without worrying about finances or legal barriers. (My father eventually visited Guyana, one of our last trips together before he died a few years later, and took to the country so much that he wanted to do Peace Corps himself one day.) And I did leave, feeling a mixture of reluctance and relief when I got on the plane.

I can admit now my love affair with Guyana wasn’t always pretty. The relentless humidity was unbearable at times and I grew tired of waking up sunburned, our curtains no match for the sun. I refused to douse my meals with wiri wiri pepper and was often met with the sucking of teeth in return. I honestly wasn’t fond of teaching and I can’t say what impact, if any, I had on my kids except having them memorize the lyrics to Nas’ “I Know I Can” while makeshift drumming on their desks.

But for that brief time in my life, thirteen years ago, New Amsterdam belonged to me. It was marvelous.

For many of these artists, Un | Fixed Homeland is their view of what living on the outside means. For me, it only makes me want to get back in.

See also: celestehamiltondennis.com

Recent Comments