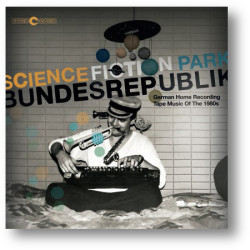

In October 2014 Finders Keepers Records released a compilation of music from the home recording scene of the early 1980s in Germany. This important collection documents the mood of those times, as well as representing the primeval ooze out of which the Neue Deutsche Welle evolved. The music has lost none of its actuality today. With kind permission we reprint here the liner notes written by the curator and dadatronic musician and composer, Felix Kubin.

— Fred Roberts, Music Editor

* * *

Science Fiction Park Bundesrepublik

by Felix Kubin

Noise Obsession Out of the Living Rooms

In the summer of 1982, in a cottage in the Bavarian forest a 13 year old boy sits with his brother on the sofa and stares at the television. What he sees will transform his life. In rapid, revue-like sequences, young costumed people jump around in front of a painted background. They serenade tulips that are sparingly lit, twist and stretch under rubber sheets and with eyes taped over, iron on empty boards. Sometimes they just stand there, staring brazenly or absently into the camera, cryptic texts intoning through stiff mouths. The entire spectacle might be a direct transmission from Mars. The music accompanying all this is so radically new that the terminology to describe it doesn’t exist yet. Most of all, it is unexpectedly bizarre, minimalistic and electronic. The astonishing performance is garnished by four amateurish dancers obviously assigned to the musicians by a decree of the TV broadcaster. Nothing fits together, yet the combination is pure genius. The demeanor of the group is so shockingly modern and uncompromising that the boy in front of the television has to repeatedly pinch himself to prove he isn’t dreaming. This is the music he has waited years for. This is his music, and it sets off a catalytic spark in him. His little brother is drafted to write down the names of the bands: Palais Schaumburg, Der Plan, Deutsch-Amerikanische Freundschaft, Lorenz Lorenz, Der Körper und die Seele (The Body and the Soul)… One can imagine the creative spelling that made it onto the list.

In the summer of 1982, in a cottage in the Bavarian forest a 13 year old boy sits with his brother on the sofa and stares at the television. What he sees will transform his life. In rapid, revue-like sequences, young costumed people jump around in front of a painted background. They serenade tulips that are sparingly lit, twist and stretch under rubber sheets and with eyes taped over, iron on empty boards. Sometimes they just stand there, staring brazenly or absently into the camera, cryptic texts intoning through stiff mouths. The entire spectacle might be a direct transmission from Mars. The music accompanying all this is so radically new that the terminology to describe it doesn’t exist yet. Most of all, it is unexpectedly bizarre, minimalistic and electronic. The astonishing performance is garnished by four amateurish dancers obviously assigned to the musicians by a decree of the TV broadcaster. Nothing fits together, yet the combination is pure genius. The demeanor of the group is so shockingly modern and uncompromising that the boy in front of the television has to repeatedly pinch himself to prove he isn’t dreaming. This is the music he has waited years for. This is his music, and it sets off a catalytic spark in him. His little brother is drafted to write down the names of the bands: Palais Schaumburg, Der Plan, Deutsch-Amerikanische Freundschaft, Lorenz Lorenz, Der Körper und die Seele (The Body and the Soul)… One can imagine the creative spelling that made it onto the list.

Back home, in Hamburg, as if possessed, the boy begins to experiment with synthesizer, home organ, voice and tape recorder. He is not the only one to begin explorations in this direction. The entire Federal Republic of Germany is just at the boiling point. A new form of home music is coming into existence. It has nothing to do with violin-playing children, scratchy sweaters and well-combed relatives listening on the sofa, but rather combines the fears and dark abyss of industrial society. Remarkably it is the same industry that made the tools available to the raging youths: cheap Casio keyboards, synthesizers, drum computers and 4 track tape recorders. Suddenly anyone can acquire his own means of production to use in protest against the industrial forces. What is happening here? Marx paradox? Auto-subversion? This polyphony of creative aggression rolling suddenly towards the industry bosses was not something the gentlemen electro-engineers could have foreseen – not to mention those unbelievable lyrics! Ready for a sample?

Roaring Cloud Babies

Riding in tiny motorboats

Searching over the river

And they have spotlights,

Searching the shore

Searching for me and you

And they have spotlights

And cameras”

(Andy Giorbino, „Stadt der Kinder”) (City of Children)

“I say yes,

I say no

I turn off, I turn on

My ego radiates

My ego radiates

No, yes, no, yes

Turn me on

Turn me off

(Holger Hiller, “Ja Nein”)

In Germany especially, that neurotic country whose dark Nazi past and subsequent East-West division filled its closet with skeletons, the electro-industry’s advance falls on fertile ground. The 4-track tape studio becomes the medium of the collective unconscious, becomes the embrasure, the lighting rod and the magnetic witness to the fears of an imminent nuclear war. On top of that most of the recordings are born without strategy or intention of commercial exploitation. They are eruptions out of the crater of a society that had reached a deadlock during the so-called German Autumn with its failed RAF movement. Everyone was waiting…but for what? For the end of the world, approaching via an insane arms race? A new youth movement? A new kind of ice cream?

Alfred Hilsberg, founder of what is probably the most famous German independent label Zick Zack puts it this way: “In Germany there was nothing. There was no real musical culture. So the people here – encouraged by the punk movement in England – began to develop something of their own. It was purely a strategy of survival.”

The conventional opinion that Germans should go down to the basement to laugh finds here its practical application. In the home recording basement one can pursue unobserved one’s pent up fears, frustrations, aggressions and bizarre fantasies. The simple-mindedness with which frequencies are mistreated and lyric reminders are slashed into knees brings out a surprising originality. The new heroes are the amateurs of the electronic circuit, their behavior is unpredictable and driven by impulsivity. The (post) punk mode of action predominates: fast and to the point.

In their freshly established home studios the protagonists practice the new underground music, the “undirected aggression of liberated sounds,” as Frank Apunkt Schneider expressed in his book „Als die Welt noch unterging“ (“As the World was Still Ending”). Everything that isn’t nailed or riveted down is used as an instrument: baking trays, cartons, room lamps, toys, wooden flutes, whistles, cans, trays, record players, televisions, a doorbell, a telephone. Out of the living rooms of the nation drones an obsession with noise, sparing not even the children. For example, 1983 saw in the outskirts of Hamburg what is probably unique in the history of music: a scene of experimental kid’s bands terrorizing their neighbors under assumed names like “Universalanschluss“ (Universal Connection), “Intensive Styroporsymbole“ (Intensive Styrofoam Symbols), “Die Egozentrischen 2“ (The Egocentrical 2), “Der Leichenwäscher von Boberg“ (The Corpse Washer of Boberg) and “Rekronstruirtes Relativpronomen“ (Reconstructed Relative Pronouns).

At the same time somewhere in South Germany, two brothers proclaim the “Republic of Tape Delinquents”. By this time the phenomenon is finally official. Kitchen debates in conspirative circles:

“What does a typical tape delinquent look like?“

“They look completely normal.”

“No trace of underground?”

“Only to the extent that no one suspects they’re producing cassettes. They’re lone warriors mostly.”

30 years later. I meet Beate Bartel (CHBB) and Klaus Hoeppner (Cinéma Vérité) in Bo Kondren‘s Berlin master studio. Eyes light up. Using a screwdriver, Bo adjusts the speed regulator of the tape deck, to optimize playback. During the East German era he was part of the cassette scene, those days in East Berlin, where one could be taken into investigative custody for the distribution of subversive music. Bringing tapes with irritating sounds into circulation was an act of political disobedience.

As time condenses on the walls I wonder if things have truly changed that much since then. Today same as then the end of the world is prophesied, same as then the nations are beating each other’s heads in, if the line of demarcation is no longer between East and West but between Koran and Bible. In the economy money is made with money and difficult music is not played on public radio. The largest difference is perhaps that the old distancing techniques of the ’80s have been permanently replaced by “I like” Thumbs up, you are all my friends, always. Alfred Hilsberg is not so excited about that: “Today via the Internet people are connected like never before, but they remain isolated. No one receives real feedback anymore, encouraging one to meet others. The independent movement of the late ’70’s and ’80s was born of social energy.”

So here we sit together, in reunified Germany, overpowered by the originality and actuality of the old recordings. These were obsessive-compulsives at work, in service to the cacophonous Spirit of the World, which, despite all the dark circumstances, carries these words optimistically in its heart: “We’re still living, it’s you who are dead!” Or as the Düsseldorf group “Der Plan“ so accurately stated: “The world is bad, life is beautiful!”

And what became of that 13-year-old boy who sat in front of the television back then? He hasn’t had a television for the last 25 years and is just now writing these lines. His enthusiasm for the cassette scene has remained to this day. And while collecting the pieces for this compilation he had to keep pinching himself in the arm.

(translated from German by Fred Roberts)

Label: http://www.finderskeepersrecords.com

The TV broadcast Felix saw: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QwdZm1Uo0FQ

Part of a lecture on the tape delinquents by Felix Kubin: https://vimeo.com/74927910

Related podcasts at Macba, Barcelona Museum of Contemporary Art:

http://rwm.macba.cat/en/curatorial/deutsche_kassettentaeter_1_felix_kubin/capsula

http://rwm.macba.cat/en/curatorial/deutsche_kassettentaeter_2_felix_kubin/capsula

http://rwm.macba.cat/uploads/20110829/05Interruptions_eng.pdf

Recent Comments