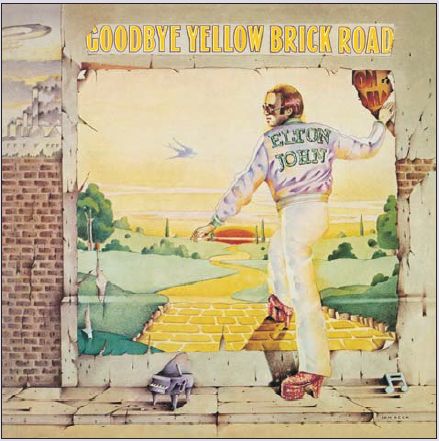

The making of the album cover artwork for Elton John’s Goodbye Yellow Brick Road

Interview with David Larkham

by Mike Goldstein,

Contributing Writer

Founder/Album Cover Hall of Fame

Originally posted April 18, 2014, with updates added April, 2018

Like great music, great art always stands the test of time.

Like great music, great art always stands the test of time.

Elton John’s Goodbye Yellow Brick Road came as the result of several short-but-very-productive song-writing/recording efforts by Elton, Bernie Taupin, his band mates and his producer and, although the record received rather lukewarm reviews from some critics at the time, it went on to be Elton’s best-selling studio recording, from which emerged his much-beloved show opening sequence (Funeral For A Friend/Love Lies Bleeding), three huge hit singles (Bennie & The Jets, Saturday Night’s Alright For Fighting and the title cut) and a song (Candle In The Wind) – originally written in honor of Marilyn Monroe and re-written in 1997 as a tribute to the passing of Princess Diana – that then became the second best-selling single of all time. His seventh studio record, it was undeniably the record that launched Mr. John into the Pop music stratosphere.

So although we have to ponder the critics and their ability to appreciate a work’s overall importance in both the portfolio of an influential artist and the ongoing development of the Pop music genre, no such difficulty exists when considering the enduring impact of designer/illustrator/photographer David Larkham’s portfolio of work produced for Elton John throughout the years. The original package for this double album – and its 3-panel design – was also, in itself, quite unique and memorable. With that much album real estate to fill, it was an extraordinary feat accomplished by the album cover team who delivered six panels of impressive design, illustration, photography and typography, featuring individual illustrations for each song included on the record as well as the lyrics which, at least for me, made the listening experience all the more enjoyable (and dependent on having the album cover close at hand).

Late 2013 marked the 40th anniversary of Goodbye Yellow Brick Road‘s release and, in March, 2014, an imposing 40th anniversary “super deluxe re-release” package was produced containing five discs (two of which were of a particularly well-performed 1973 concert played in London’s Hammersmith Odeon and another containing covers of GYBR songs by a number of current musical faves) and a DVD of a documentary titled Elton John and Bernie Taupin Say Goodbye to Norma Jean and Other Things. The set also included a 100-page illustrated hardback book of rare photos, memorabilia and articles containing interviews with Elton John and Bernie Taupin. The “goodbye” theme was again brought to bear when, in January, 2018, Sir Elton announced his intention to embark on what will be his final live tour, with “Farewell Yellow Brick Road” shows scheduled all over the world over the course of the next three years, so now seemed like a very good time to revisit and update the original interview I’d done with David and share it with readers and fans as we bid a slow-but-sure farewell to one of rock’s best-loved performers.

I caught up with Mr. Larkham in late March of this year and have worked with him since to bring ACHOF fans an updated, behind-the-scenes look at how this remarkable album package was conceived and assembled by a team of highly-talented artists, working with a client who was about to become the biggest pop star in the world….

Mike Goldstein, Album Cover Hall of Fame – David, thank you so much for taking time out of your busy schedule to work with me on this interview. I’ve seen some of your recent online branding work for the J.J. Hapgood General Store here in the U.S. (www.jjhapgood.com) and, like all of your work, it certainly gives the viewer an excellent sense of your client’s image while, at the same time, motivating me to visit Peru, Vermont for a wood-fired pizza! With that being said, let’s take you back 45 years and talk about your work for Elton John.

To begin with, would you please tell me how and when you first were contacted by Elton John or his management or record label about this assignment? Had you worked with Elton or his label before and, if so, would you please provide some of the details of that previous relationship?

David Larkham – Goodbye Yellow Brick Road was recorded in 1973. I first met Elton in 1968 after a friend at his record company – DJM Records – had asked me to take some publicity photos of two unknown songwriters they had signed – Reg Dwight and Bernie Taupin. In those pre-fame days, this was not some momentous occasion since Elton – that is, Reg – and Bernie were just regular guys you might meet in a coffee bar. The record company friend, Steve Brown, was to become Elton’s long-time creative advisor. In 1968-69, Steve and his wife would put up with Elton, Bernie and myself as weekend houseguests – hanging out together, visiting the cinema, playing soccer or tennis, going out to a café or the pub, etc. Eventually the friendship evolved to illustrating Elton’s first album cover for Empty Sky. We all liked both the recording and the naive packaging for a few days, but then there was a pretty sharp learning curve between that and the next album – Elton John – for which I also art-directed and designed the cover. From that point in the late 60’s on throughout the 1970’s, I was increasingly involved in all of Elton’s design work. Either freelance or in-house at DJM Records, in the States or the U.K, I designed, art directed, illustrated, photographed or had a hand in all of Elton’s “Classic Years” LP packaging.

Mike G – So, in your opinion, what made Elton John – the artist and his music – different from other artists in his “category” or of his day?

David L – What made Elton stand out from other artists? Well, the late 60’s were at the tail-end of an era when music publishers would sign songwriters like Elton, and Bernie Taupin and then tout their songs around to established stars. In the States, you had a similar set-up through the 50’s and 60’s with Brill Building songwriters like Goffin and King, Lieber and Stoller, Sedaka and Greenfield, Pomus and Shuman,and Mann and Weill, who were all churning out hits for other artists. Elton and Bernie were initially expected to produce “moon in June”-type songs about romance until Steve Brown encouraged them to write their own stuff and to be true to their own material. So, Elton’s fluency as a tunesmith, fusing lots of pop forms – allied to Taupin’s poetic, almost cinematic imagery – was all very different to the usual run-of-the-mill stuff. Similarly, Elton and Steve Brown’s decision to start working with producer Gus Dudgeon and arranger Paul Buckmaster produced a rich, orchestral and very individual approach to the music for the Elton John album in 1970. Also a plus – Elton has a great, immediately recognizable voice.

MG – Was it your plan to develop an overall design concept first for this record package, or did you have specific imagery and a design guide in mind for anything that might be used for this record cover concept?

DL – By 1973, I’d been working for a number of years with Elton, Bernie, their management and record label, so I was very much part of the team. They’d recorded Honky Chateau and Don’t Shoot Me I’m Only The Piano Player in France, and it was decided to record the follow-up in Kingston, Jamaica. The album had no title at that stage. By that time, I was living in Los Angeles, as was my designer pal Mike Ross, and we’d co-art directed and designed Don’t Shoot Me I’m Only The Piano Player together, as well as other material for other artists. Elton, his band, management, producer, etc., all flew from Europe to Jamaica, and I decided to go there for a few days as well. This would enable me to hear a bit of the music and get a feel for the album.

As it was, the recording studio that was chosen in Kingston was not technically sound, and so there were some boring days of waiting for new recording equipment to be flown in. Elton is not a great one for sitting around hotel swimming pools and, one day, partly to alleviate his boredom and partly to give me a taste of the songs he’d written so far – he and I went off to the recording studio. There, he sat at the piano on his own and played and sang the songs to me – Elton John, playing to an audience of one! I felt very honored, and it gave me the chance to appreciate the diversity of the songs and to get a good “feel” for the music. Inspired, I returned to Los Angeles and the rest of the entourage soon returned to Europe when this attempt to record in Jamaica was aborted.

You’ll recall that the album had no title at that stage but, with the talk favoring a double-album so as to include the large amount of new material, Mike Ross and I proposed a triple-panel fold-out for the packaging. There weren’t a lot of them around at that time. We saw the three center panels as ideal for a lyric spread and, since we had copies of Bernie’s lyrics, we decided to do separate illustrations for each of the songs. This was something we got started with while the album was being recorded in Europe, and we were sent the lyrics of any additional songs that were added as they recorded.

MG – What were the inspirations for the particular images chosen for the album art?

DL – As mentioned, I had heard the bulk of the songs when Elton played them to me in Jamaica in January, 1973. After some local unrest – including hub-bub created by the Frazier vs. Foreman boxing match taking place in Kingston – brought an end to those recording sessions, they were rescheduled for May 1973 in France (Editor’s Note – they took place over a 2+ week stay at the Chateau d’Herouville outside of Paris, the “Honky Chateau” made famous in a previous recording and where a number of fine records were recorded in its studio, including Elton’s Don’t Shoot Me I’m Only The Piano Player, David Bowie’s Pin-Ups and Low, and for acts including the Bee Gees, Canned Heat, Fleetwood Mac, Marvin Gaye, Iggy Pop, Jethro Tull, Cat Stevens, T Rex, Uriah Heep, Rick Wakeman and others). In Los Angeles, Mike Ross and I were working on the illustrations for each of the songs – there was no album title at that stage, therefore no image concept for the cover. By Summer, though, we heard from London that [a] “Goodbye Yellow Brick Road” was to be the title; [b] a suggested fine-art portrait of Elton, painted in early 1973 by world-renowned portrait painter Bryan Organ, for the album cover was considered inappropriate, and [c] they may have found an image they wanted to use – an album cover image that had been used previously by another act! Oh, and [d], I was to catch a flight to London immediately.

MG – So, what then? How did you ultimately settle on a design concept and then choose the talent who would work with you on this effort? Also, can you please clarify who actually did the drawings, lettering, etc.?

DL – ‘Goodbye Yellow Brick Road’ is a song about leaving the grimness of the city behind – and a failed romance – and going back to the preferred pleasantness of the countryside. In London, the album’s coordinator Steve Brown believed he’d found an image by the illustrator Ian Beck – someone whose work we’d previously seen and admired – that we could use and so, on a Thursday in L.A., I was told to gather up all the lyric illustrations that Mike Ross and I had done and get on a plane to London. The plan was to try and make final decisions on the album packaging, as time was running out fast. While I was flying from L.A. to London and working on some of the center-spread illustrations at the same time, Steve Brown was meeting with Ian Beck in London. Steve had seen the LP cover for Jonathan Kelly’s Wait ‘Til They Change The Backdrop, which he felt fitted the city/countryside concept. Steve wanted to buy the illustration outright and then re-use it for Elton’s Goodbye Yellow Brick Road!! Now, you and I know that’s a non-starter of an idea, and Ian Beck politely pointed out that you couldn’t have two albums released with the same front cover image, as Kelly’s album had been out less than a year. But it was decided then that Ian Beck would work with us to produce something new for Elton.

MG – Go on…

DL – So, I’d left L.A. on Thursday afternoon and landed in London about Friday breakfast-time. A car took me to Elton’s offices in the city centre. I was understandably a bit jet-lagged, but Steve Brown, Ian Beck and I had a talk and a look-through of Ian’s portfolio. Once we’d heard the album title that day, I then had a vague thought of seeing Elton somehow stepping onto a ‘yellow brick road’. Similarly, I have this faint memory – whether that was an image seen on the way to LAX, in an on-flight magazine, or perhaps at Heathrow (London) airport – that I must have seen an advertising piece of a man staring at a travel poster on a wall. Wherever it came from, it was part of the discussion between Steve, Ian and myself.

MG – When all was said and done, did you consider your final efforts to be works of your own self-expression, or do you attribute the final designs to the leads from your clients?

DL – Having seen Ian’s work on Wait ‘Til They Change The Backdrop plus a cover of Cream magazine that Ian had done featuring David Bowie with a city-wall background of posters and then adding in my thoughts of ‘Elton stepping onto a brick road’ and ‘ man staring at a poster’, I think you can see how the image for the front of GYBR evolved through discussion. So… the outer cover wasn’t an effort of self-expression, it came about through a meeting of minds.

MG – so, in the end, how long did it take you to develop the finished image, from concept to final product? Were there any special processes, materials or other aids used? Can you give me an estimate of the number of images that were considered or submitted before the final decision was made?

DL – Let’s see now – I’d arrived in London on Friday, but had to be back in L.A. by Monday evening for a Tuesday commitment. On Friday, we mapped out the look of the outer spread of the three panels for the package and Ian went away to do the rough layouts over the weekend. Also over the weekend, I stayed with Steve Brown and his wife, spending the time doing a trace layout for how the lyrics – plus illustrations for each song – would fit. We met up in London on the Monday morning to review what we’d done. Ian had done the layouts as three sketches made onto detail paper – a thin paper, almost like tracing-paper. They were colored in with crayons to give the impression of the front cover, a poster area for credits on the back cover and photos as posters on the third panel. I had to leave London, but everything was left with Steve Brown – who was then assisted by graphics man David Costa – to pull all the loose ends together. Ian then had ten days to complete the illustrations for the outer cover.

He used a Polaroid he’d taken of a friend “stepping into a poster” as his reference for where his illustration of Elton would be seen on the front. His final art was done onto three separate watercolor boards. Ian said that he did them in mixed media – watercolor over pencil, and that he added parts of it with chalk pastel and colored pencil. He applied the larger flat areas of color with pastel and cotton wool.

GOODBYE YELLOW BRICK ROAD

MG – With all of the advice and assistance of folks from the record label you were getting – in the process of deciding what you should produce – do you feel that you were given the resources to do what you wanted to do? In the end, were they happy with the results? How did they express that to you?

DL – Everyone was very happy with the packaging, and in England, it won Music Week‘s “Album Cover of The Year” – the British equivalent to a Grammy Award.

MG – In a recent interview I read with you and Ian B. on the same topic, Ian said that the front cover image of Elton peeling back an image on the wall he was stepping into and exposing a corner of the cover of the previous record was done at the request of management to help illustrate the transition from one record to the next. Any comment?

DL – As I mentioned before, I’d flown into London on a Friday, spent two days and a night doing trace layouts for the lyric centre-spread, and was therefore exhausted by the time I reconvened with illustrator Ian Beck and album coordinator Steve Brown on the Monday morning. It’s possible that Steve and/or I mentioned the Don’t Shoot Me… inclusion at that stage. After 40 years, it’s tough to remember every detail – particularly if mind and body was burnt-out at the time…

MG – If you can think of anything else that might help readers better-understand what your experience was during this project, I would appreciate any other anecdotal info you’d be willing to provide. Again, anything you’d be willing to share would be treated with the utmost respect !!

DL – I think I’ve been fairly descriptive of events during the Yellow Brick Road project. When we were waiting around in Jamaica for the eventually abandoned recording sessions to start, I’m afraid I have nothing to report on disruption, drink, drugs or depravity. In fact, we all did our own thing during the day – reading, sitting by the pool, killing time – but then got together each evening and shared dinner around a long table that included the musicians, wordsmith Taupin, producers, engineers, management, instrument techs and myself – plus wives and partners. It was a communal, friendly spirit. At the time when Elton was the biggest-selling star in the firmament, for him to take time out to play me the songs he’d written – playing to an audience of one – I think that demonstrates his amiable-yet-pro-active and professional approach to record making.

MG – In a 2010 BBC interview, Elton described this 80-minute double album as his White Album. I’m assuming that he said this as it was The Beatles’ most commercially-successful record but, as you know, that record’s packaging by artist Richard Hamilton has also been praised as a “game-changer” in album cover history, as it reflected the Minimalism that was emerging in the fine art world at the time. I’d like to know two things from you – first, what were your initial impressions of the cover for the White Album when it was first released and second, were your design ideas for GYBR paying homage to any particular aspect of Pop Culture or Fine Art at the time?

DL – The “White Album”… my first reaction to the idea was appreciative laughter – “Why hadn’t anyone done that before?” But after that, part of it was the acknowledgement of Richard Hamilton’s admiration for Marcel Duchamp – the artist credited with the foundations of conceptual art, and someone with a great sense of humor. The UK version of the initial release of the White Album cover had ‘The Beatles’ name embossed as well as each copy being individually numbered. You can see it as a bit of conceptual art – with humor thrown in, as I think Hamilton’s vision was a numbered, world-wide, ‘limited-edition’ of millions and millions. Of course, given territories and printing restrictions – that wouldn’t work out over time, but a great concept nonetheless.

I remember the real cachet at the time was to try to get a very low numbered ‘limited-edition’ of the White Album. And, if you’ll forgive an aside, I was already associated with people at Apple – the Beatles head-quarters – trying to produce a ‘glow in the dark’ album-cover idea for one of their signings. In November 1968, it was technically and financially almost impossible – but I was hugely interested to note your recent interview with Shauna and Sarah Dodds about their ‘Long Night Moon’ cover. Big respect to them for their vision and research to achieve their ‘glow in the dark’ design. Anyway – to cut a long story short – through Apple I was able to gain a low numbered ‘limited-edition’ of the White Album, though where my copy is now, I haven’t the faintest idea.

As to GYBR design ideas, there was no conscious Pop Culture or Fine Art influence. The prior album cover had a title suggested by Elton – Don’t Shoot Me I’m Only The Piano Player and, being a fan of French Nouvelle Vague cinema, I immediately picked up on film-director Francois Truffaut’s ‘Tirez Sur Le Pianiste’ – Shoot The Piano Player. Hence the cinema scenario for the front of the album cover – a bit of conscious Pop Culture homage. With ‘GBYR’, there was nothing like that, though, having said that, I do have a love of the surreal – as may Ian Beck, and perhaps some unconscious influence crept into the ‘step into the wall’ image.

MG – David, if you don’t mind, I’d like to ask you a few more questions about some general topics I’d be interested in getting your opinions on. First off, with the electronic delivery of music products growing at a fast pace, are you noticing any more or less enthusiasm on your client’s behalf to invest time and money in packaging that stands out?

DL – My personal circumstances over the past ten years or so have meant a gradual tapering off in everyday music business involvement, though I’ll still do the odd bit of album packaging if you ask me nicely. Besides music stuff, my work began to embrace things like serving up restaurant graphics, retail detail, or embracing illustration and design for the theatre. In addition, I illustrate for fiction stories and I paint commissioned portraits and other fine-art projects. Consequently, I don’t follow album packaging as closely as I used to. However, I’m still very visually aware of what’s going on and – if I can take artists I’ve worked with as examples – Paul McCartney’s recent New is a case in point, displaying his very personal involvement, with no expense spared. Similarly, consider the Elton John/Leon Russell collaboration in 2010 called The Union, where Annie Leibovitz was asked to photograph the pair. She’s not someone who comes cheaply and, for Elton to suggest submitting himself to a photograph is almost a miracle, since he absolutely hates, hates, hates (!!) sitting for photo-portraits. This is an example of investing large money, in a spirit of self-sacrifice, to produce tasteful, quality packaging.

So, I think that – as with the 1970’s, when 12″ album covers ruled the world – some musical acts still demonstrate great interest and passion for the packaging of their music. They get personally involved and spend what is necessary to achieve their aims. And, as with the 70’s or whenever, there are those who are content to leave these things to management or to the record company as long as very little cost comes out of their royalties. As with earlier years, some people are keen enough to invest time and money in visually creative things – other artists/managements/record companies don’t. I guess ‘twas ever thus.

MG – So, can you summarize your feelings about album artwork and design these days? Are there any designers or musical acts that you think are keeping the field alive or important? Do you think album art matters anymore?

DL – I ALWAYS think album art matters – I think it’s hugely important! If you ask artists, fans, music industry types – they’ll all express a preference for the 12″ album covers from the vinyl era. However, a well-done CD cover is equally as important. As we all know, size doesn’t matter – it’s what you do with it that counts! Certain individual musical acts keep album art alive, and I think it shows in their work – McCartney and Elton are but two examples. As to any of the work of individual designers – as I mentioned, I have less day-to-day involvement in album art. I can certainly go through CD racks in a record store and whistle aloud with admiration at certain cover images, but I’m not that enthusiastic as to purchase those particular CDs in order to open them up just to check out the design or photography credits and so, consequently, I have less of a grasp on names than I used to. But I know what I like.

MG – In your opinion, how does album cover art help us document human history? Personally, I believe that iconic album cover art – in many ways – has had a noticeable effect on Pop culture, so I’d like to get your take on this – is the imagery and music providing the direction, or is it reflecting the culture, or ??

DL – An art school mantra is “Form, Fashion and Function”, and great album cover art will follow what is fashionable in music and pop culture, while at the same time setting their own trends as visual legends in their own right. I’m thinking of covers like Peter Blake’s Sgt Peppers, Warhol’s Sticky Fingers or “Dark Side of The Moon from Storm (Thorgerson) and Po (Aubrey Powell) – to name but a few. Most very good, iconic album cover art is both a reflection of what’s current, and an influence on culture. As The Beatles said “The love you take is equal to the love you make.”

MG – While doing the research for my book and for some of the bios featured on the ACHOF site, I found examples of something that made me want to work harder to make sure that credits are given where due – those being several incidents over the years where an artist’s work had been used – and, on occasion, abused – by labels, print publishers, licensing companies and/or other musical acts without permission or without giving proper credit for the work being used. It seems that, in an age where people seem to find it permissible to “borrow” – it sounds so much better than “steal” or “plagiarize” – an artist’s work to help them promote and sell their own products, folks that create original art have been forced to police traditional and online media outlets to do what they can to either stop this unauthorized use or, at least, receive credit for the work they’ve done. Have you – or any of the artists you’ve worked with – been victimized in this way? Is there anything that can/should be done about it, or do you simply chalk it up to being one of the costs of doing business these days?

DL – I wouldn’t have time to police the web, so there’s probably lots that I might miss. A few years ago, Mike Ross, my co-art director on Goodbye Yellow Brick Road, spotted that Giorgio Armani were using the illustration from “Saturday Night’s Alright for Fighting” as a motif for posters, labels and part of store window displays. We checked around, and – a sort of UK ‘statute of limitations’ meant that we had run out of time to litigate.

It’s a tough subject; I remember years ago logo-meister Tom Nikosey developed an illustrated logo for The Commodores. He had quite a job persuading Motown that they couldn’t just keep on using it again and again without paying him – he was the copyright owner after all.

So, to answer whether I believe that there’s anything that can/should be done about it, all I can say is that if you had the time to ‘police’ the web, plus every magazine/CD package that comes out – then you’d have the opportunity to go to court. Otherwise – I think that, unless you spot something – it’s just one of the side-effects of business these days.

MG – one final question, as the curator in me always wants to know details like this one – can you tell us what happened to the original artwork for this release?

DL – This was 1973 – an era before there was deserved reverence to the designer, illustrator or photographer and their ownership of original art and copyright. There was an assumption at the time that, having paid for an illustration, the record company owned it. For Goodbye Yellow Brick Road, Ian Beck remembers bringing his three illustrations in to the record company, and overhearing one executive say “Oh, I like that bit – I’m having that.” That tells its own story, and thus – the original art is lost in the mists of time.

Editor’s note – if you are that aforementioned record executive, or someone who knows him or her – please have them get in touch with me here just to let me know that these works are still around and being enjoyed by those that are lucky enough to see them on display in their home…

If you’d like to learn a bit more about “the making of” Goodbye Yellow Brick Road, here’s a link to a nicely-produced video interview with many of the people involved in the 2014 project, along with tidbits of the newly-recorded record of songs from the album re-worked/re-interpreted by some of today’s best musicians – http://www.youtube.com/watch?feature=player_embedded&v=dw7aHBJJi-A

About the artist, David Larkham –

A partial list of notable album cover credits includes – Elton John – Elton John, Tumbleweed Connection, Madman Across The Water, Don’t Shoot Me I’m Only The Piano Player, Goodbye Yellow Brick Road, Captain Fantastic & The Brown Dirt Cowboy and Greatest Hits; Three Dog Night – Cyan and Hard Labor; Steely Dan – Pretzel Logic; Leo Sayer – Endless Flight; Ambrosia – Somewhere I’ve Never Travelled; Paul McCartney – Pipes of Peace; Van Morrison – Too Late to Stop Now and Bryan Ferry – Boys & Girls

UK-born and educated, David attended the Bootle Grammar School in Liverpool and then, ultimately, the Kingston College of Art at Kingston University, where he earned a Bachelor of Arts in Graphic Design. He began his career in the arts as graphic designer for The Evening Standard newspaper, after which he worked as a freelance designer for clients such as The Observer (magazine and newspaper) and The Daily Mirror’s Mirrorscope magazine. In the early 1970’s, David moved to Los Angeles and launched Tepee Graphics/David Larkham & Friends studio, working closely with photographer Ed Caraeff on a number of well-regarded music industry projects, including work for John Reid Enterprises (Elton John & Queen), MCA, CBS and Warner Bros. Records and Universal Film Studios.

After 10 years working in California, David re-located back to London, where he gradually morphed from a senior designer at London’s Cream Limited Agency into the co-proprietor of a music/entertainment related advertising agency called The Complete Works. In addition to doing packaging work for various acts and record labels, David’s team also helped Tower Records launch into Europe, and represented quite a few concert promoters and booking agents. Their major client was Solo Promotion who – during the 80’s, 90’s and “noughties” – handled live event duties for a range of acts including The Rolling Stones, Phil Collins, David Bowie, Genesis, Simple Minds, Suzanne Vega, The Spice Girls, Celine Dion and many more. Other clients promoted acts such as Fleetwood Mac, Bob Dylan and too many others to mention. For these artists, Larkham was involved in creating graphics for posters, publicity, press kits, pamphlets, programs, passes, press-ads, promotional merchandise and propaganda – for one-off events, European tours, world tours, etc. They also handled radio and TV advertising – in those days of pre-internet publicity.

David also worked on a wide range of projects for The Sanctuary Group, where he served as art director and designer for Iron Maiden for a number of years during the 80’s and 90’s, concentrating on music packaging (LP’s, Video and DVD covers from the era of – Seventh Son of A Seventh Son, Fear of The Dark, A Real Live One, No Prayer For The Dying, A Real Dead One, Infinite Dreams, Maiden England, etc.). In the early 1990’s, David joined the Haymarket 2 agency as their Art Director, working on campaigns for a wide variety of clients and remaining there until 2001, when he launched his own graphic design consultancy called David Larkham Ink and continued work with previous and new clients such as The Sanctuary Group, Universal Music Group, MPL Ltd (Paul McCartney), 21st Artists Management and Mersey Beat magazine, among others.

In 2013, David produced the cover art for a book by author Keith Hayward (and published by Soundcheck Books) titled Tin Pan Alley: The Rise of Elton John. He also continues to paint serious fine art and portraits. More recently, in November, 2016, David was again in the news after showing us some examples of his newer works, such as the fine art portraits he’s created using a fascinating pixel-based technique he’s perfected. David sent me a link – https://youtu.be/F98rYAaUZ9A – to a video he’s created that shows him producing his latest work, a portrait that was – at least in a parallel universe – an introduction to who he’d expected to be the winner of the 2016 U.S. presidential election, thus giving us the title for the 3-minute “making of” film he’s produced that features the music of Late Show with Steven Colbert‘s house band, Jon Batiste & Stay Human). According to Mr. Larkham, “Paintings like ‘Hillary’ take about 3 months – though not working every minute of every day. This one was started when I assumed common sense would prevail. The election surprised the world. A new title concept has salvaged a good video concept. One reaction to the video was that it was ‘bittersweet’”.

About this AlbumCoverHallofFame.com interview –

Our ongoing series of interviews will give you, the music and art fan, a look at “the making of” the illustrations, photographs and designs of many of the most-recognized and influential images that have served to package and promote your all-time-favorite recordings.

In each interview feature, we’ll meet the artists, designers and photographers who produced these works of art and learn what motivated them, what processes they used, how they collaborated (or fought) with the musical acts, their management, their labels, etc. – all of the things that influenced the final product you saw then and still see today.

I hope that you enjoy these looks behind the scenes of the music-related art business and that you’ll share your stories with me and fellow fans about what role these works of art – and the music they covered – played in your lives.

A fine selection of ACHOF interviews with many of the most-talented and influential album art/packaging makers active in the Rock/Pop music era will be available in my new book (available Fall, 2018) titled Unsung Heroes: Stories From Your Favorite Album Cover Makers. More info on this book and its availability can be found on the ACHOF site at https://albumcoverhalloffame.wordpress.com/info-page-for-the-unsung-heroes-album-cover-artist-book-by-mike-goldstein/

Except as noted, all images featured in this story are Copyright 1970 – 2018, David Larkham Ink – All rights reserved – and are used by the artist’s permission. Except as noted, all other text Copyright 2014 – 2018, Mike Goldstein, AlbumCoverHallofFame.com (www.albumcoverhalloffame.com) & RockPoP Productions – All rights reserved.

Michael Goldstein is a writer/editor, and founder of the AlbumCoverHallofFame.com

Recent Comments