This Amazing Cage of Light

by Martine Bellen

ISBN-13: 978-1941550328 – Paper/$18.00

Spuyten Duyvil: 2015

Review by Tom DeBeauchamp

In “Cuccina,” one of the poem’s in her new collection, Martine Bellen writes, “The most beautiful order is still/A random collection/Of things insignificant in themselves.” Wherever you look, whatever you hear, each of the world’s phenomena has meaning only in its relationship to other phenomena. Meaning, feeling, identity apply always to these aggregates, and the orders they form in the moment of their coming to be related are singular and unique. Just as “Cuccina” is constructed of a number of images—the warmth of pastries, the wildness of bucks and does, a fall morning—all resonating together to impress an experience, This Amazing Cage of Light, Bellen’s new and selected poems, impresses new meaning into the poetic and philosophical territory Bellen has been interrogating from the very beginning of her career.

In the first of the selections, “Camisado,” Bellen writes:

“Across the bridge a basilisk waits for breath and your past with the weight of what you live—a complete description moves inside a universe indefinite because of finite matters. And stars unbounded by direction. No one must note the secret, though it may be known there is text stored in the solar nervous system, which we will never enter. The knowledge is possible but not its possession”

Human knowledge is limited by human mortality, the basilisk having death in its breath. In the early poems, the self, the soul, exists, a hard kernel, inside the boundaries of these limitations. Death, linear time, galactic night, these things are beyond us, at least in part, because as we rub against them, our sloughed skin only thickens the boundary between us. Bellen writes:

“Being detaches itself from inversion. At bottom it may collapse onto the beach at your skull, a circumstance of mortality where every wave breaks and rejoins. What you were ends frozen across the horizon.”

The threshold of the self is an icy territory. In “Time Travel and Poetry,” though, this lonely, trapped identity expands via language. Bellen structures the thaw as a philosophical dialogue set to shakuhachi music. In this future scene, the hundreds of years dead Lady Murasaki insists on the limits:

“Why would you purport to know the body of my land?

Carnal. ‘To know’ in the most intimate sense. Through the senses.”

Martine Bellen, as a character, argues for other modes of knowledge:

Language represents a way of ratifying one’s existence.

That the lover must absent himself for yearning, for desire, to occur. That

Writing embodies absence. ‘Shunyata. Form is exactly shunyata, shunyata

Exactly form.’

The form of the poem, the form of the book, of identity, are made as much by absence, what they are not, as by what they are. Writing the body of the Lady Murasaki’s land cannot duplicate the carnal knowledge of “Watching waterbirds on the lake increase in number. Taking note of flowers. The way clouds travel season to season. The Moon. Frost,” but it can, in recording them—from imagination as much as from experience—form an experience on another order, one that, while lacking the immediate material sensations of life in the world, sneaks past the monsters guarding the boundary between life and death. Poetry, as it survives its poet’s physicality, is communication across time. Bellen writes:

“The way a line might wander off and speak to a stranger. A spell might be cast. Powerful words that change the course of a life. Words originating from an older/other time. Older/other place. Words that have traveled far and long to meet you.”

There is hope in this, hope that glows only brighter as the collection progresses. As the closure of loss is traded for the expansiveness of absence, Bellen’s poems breathe deeper breaths. Absence becomes a field of possibility, endlessness, variation, and generation. In a sub-section to her “Tribute to H.D.” she invokes Sappho, whose remnants exemplify absence’s form:

“Leaf melody of unfinished rhymes, of rocky rhythms; rocks

Polished by water

Water beating ragged edges; they are never finished”

Bellen hears these leaf melodies in myths and legends too. She renders Calamity Jane, Belle Starr, and Pochahantas in vivid, biographical narratives. From the fragments of their lives Bellen remakes them, deepens them, and enriches them—not as physical human beings, of course—but as legends, never finished and temporally fluid, mutagenic concepts growing or shrinking in time.

“The mutation of something into else makes self-evident identity is not a relationship between objects but between times,” she says early on, and then, later:

“We are creatures in minds

Of others: musk, lichen,

Bits of landscape, stamen

Assorted forms simultaneously”

The idea of a single, stable self, rimed in ice, and cordoned off from the past and future, from other psyches, washes out in this image of flux. We are composed of the difference between times. Just as we are hosts for the myths and legends and poems we have heard, we operate as myths and legends and poems in the minds of others. This is what’s amazing about our cage of light; it’s not what we see, but all that is seen.

The phrase “Amazing Cage of Light,” comes from the 15th century Japanese poet Ikkyū. Bellen quotes him in the epigraph for “Pond Animals,” a new poem:

“We live in a cage of light

An amazing cage

animals animals without end.”

Ikkyu’s words, like the image of Lady Murasaki—or any of the other gods, heroes, creatures or archetypes that help to form Bellen’s work—comes from a long way away, hundreds of years and thousands of geographical miles. His words live now not just at the top of one poem, but radiate throughout the book. They are in every other line, and every other line is in them. Between her book’s covers, Bellen’s poems continually reaffirm the power of language—fraught as it may be—to link and form self across the gaps of time and space, perspective and identity. This Amazing Cage of Light takes the isolated, meaningless disclosures of Being and, beautifully, gives them order.

About the reviewer:

Tom DeBeauchamp lives in Portland, OR. He is writing a novel.

And now, a message from one of our sponsors:

E-mail to see how you can become a sponsor!

Mother’s Day: Song of a Sad Mother

by Carmen-Francesca Banciu

PalmArtPress (September 2015)

ISBN-13: 978-3941524477 – $19.00/paper

Product Dimensions: 8.3 x 4.9 x 0.6 inches

Mother’s Day: Song of a Sad Mother

Mother’s Day: Song of a Sad Mother

(A heartbreaking story about the communist years: when motherhood is kidnapped by duty and ideology)

Review by Felicia Mihali

What would be the most appropriate way to write about communism? Is it possible to ever explain what that oppressive regime did to people?

Each time I read a book about those years, I feel that something is missing. This may be because I have my own stories about communism and none of the books I have read so far resonated with my own memories. It is true that some of them gave me a sense of the injustice and horror, a feeling of being cheated by history. Yet I was left longing to read something that also touched the sadness, or even that sense of melancholy that underlies forgiveness.

I got this feeling almost immediately as I read the first pages of Carmen-Francesca Banciu’s book, Mother’s Day, first published in German under the title Das Lied der traurigen Mutter. Translated into English and published by PalmArtPress, this new title captures for me that missing part of life under communist rule.

Carmen chose to speak not about the horror of crimes, prison, torture or treason. But horror can be expressed in ways other than the amount of blood or number of corpses laying on the ground. Horror often lies in the veneer of decency that covers the day-to-day life and beliefs of people. It is in how the regime ruined normal relationships such as the one between mothers and daughters. It is about how dutifulness can destroy normalcy. It is about how responsibility can take over maternity. The submission to such a regime is treason to family and motherhood. Such obedience destroys humanity. No woman could be a mother under the power of this ideology.

Banciu’s book tells a story that grows out of a recollection of memories. It all starts in Berlin soon after the Wall is pulled down, in a the Adler café next to Check Point Charlie. Two women, a writer and Maria-Maria, come here every day to watch passers-by and to reflect. They both were born in Romania, abandoning their former lives under that destructive regime and now are settled in Germany. They need this oasis in the city where they can turn back to their past and remember they are simply survivors. While the writer is tapping perhaps her own story on her laptop, Maria-Maria recalls her last trip back to Romania to see her dying mother. There is no sadness in her story, and almost no regrets about the loss. When she first went at the hospital with flowers, mother greeted her this way: “I am not dead yet.” And later: “Throw them away if you cannot think of anything better to do with them.” Not much tenderness is to be found in a zealous member of the communist party who was not used to flowers. As her mother is dying, the daughter had the duty, more than desire, to assist her during those last moments when her mother is fighting to draw air into her water-filled lungs . Then the mother passed away amid the almost general indifference. Neither the daughter nor the father was much pained by their loss. The woman lying in front of them represents just a recollection of heartbreaking memories. Maria-Maria tries to build up the memory of her body bit by bit, starting with her mother’s eyes, neck, hands, palms. She knows her mother’s body but she doesn’t really know her.

What went amiss for those women driven by the best intention toward their families and country? All they wanted was to be a good employee, a faithful wife, and a careful mother. In this vision of the ideal communist woman, a wife should fill the pantry with preserves, iron her husband’s shirts and care that the kids were fed, well behaved and highly educated. Why was this so bad then? Because the politics of “better yourself” allowed for no failure, no weakness, no alternative. It was good if the party said it was. There was no free will, only submission to the rules.

I would like very much to highlight Banciu’s language, full of poetry and truth at the same time. I usually don’t pay much attention to language in a novel. What matters to me is how efficient words are to convey meaning. But this time, I had the feeling that everything was in the way it was said. The author’s use of short and sharp sentences was the most appropriate way to speak about unspeakable. They have a way of revealing the truth while concealing the drama. And Maria-Maria’s drama seems to be one of being unable to accuse. Hate a mother, yes, but not accuse her. If mothers were unjust with their offspring it was because they were trained to be so.

Mother’s Day tells a sad and very painful story about how people who accept to partake in the oppression turned into monstrous beings under the communist regime. Motherhood was taken over by responsibility, and love by duty. The language is pure poetry and the story just heartbreaking.

Undertow Overtures

by Larry Crist

Atom Press: 2014

Reviewed by Christopher J. Jarmick

Larry Crist is a much in demand Seattle-based spoken-word poet, and writer (several published short stories, and poems). His first full length collection of poetry (published by Atom Press in 2014) is Undertow Overtures, which is comprised of a selection of mostly previously published poems from the last 20 years.

Undertow is loaded with poems that jump off the page with testosterone swagger (only a few however are crude or borderline vulgar). There’s a raw, plain-spoken, street-smart, honesty that in the best poems reveal personal nuances and in a few cases barely miss their mark because they are overwhelmed with a jokey line (that will likely make you laugh anyway).

The 102 poems in this 156 page book stress visceral cinematic images and sounds with an often ironic, somewhat dark sardonic sharp sense of humor. Nearly all the poems have a strong autobiographical voice revealing various sides of the poet. Some poems are rants and complaints (but none whine) about relateable issues or experiences.

The poems that look at Crist’s past do so with an almost man-child sense of wonder, avoiding cheap sentimentality. Like in “Pictures of my grandmothers,” where Crist is looking at old photographs of people he is related to but never knew, wondering if he had known them briefly as a small child would it have made any difference?

The book is divided into four sections: Early atrocities, Man about town, Nature and natural crimes, and Literary quite contrary. Usually it is clear why the poems are placed in these sections. In Early atrocities, poems relating to some aspect of childhood (usually autobiographical) are gathered. Some relate stories of humiliation that scarred, others recall family members often without fondness.

In Man about town you’ll find several poems relating tales of getting drunk, or remembering awful jobs. There’s a poem set in New Orleans during Fat Tuesday, another relating auditioning as an actor, and it is here one of my favorite Crist poems is located. It’s about watching the Seattle Kingdome being demolished; The Day the Kingdome came down. In the poem Crist recalls:

There was the unfortunate time, I was arrested, smoking

Pot in the concourse. I listened to the rest of the game

From a small barred cell in the bowels of the dome

The M’s who had been 4 to 1 came back to win without me.

In Nature and natural crimes you’ll find poems whose titles mention chickens, sheep, a black dog, frogs, bison, cancer, Bonnie and Clyde, the Marx Brothers and Auschwitz, and ‘Eating pussy’. The titles are there for good reasons, but plenty of twists and turns exist within.

The last section Literary quite contrary has poems relating Crist’s love/hate relationship with the writing life that has chosen him. Writers and poets will connect to what’s related in these poems and although some aim for easy targets, Crist usually has a unique twist or a somewhat revealing personal take on the subject matter. If you’re a writer or poet expect to laugh out loud several times as you read these poems. Crist also cleverly writes a bio on himself in the form of a poem.

It’s easy to read all the poems in Undertow Overtures and know what they are about. Several poems when read a second or third time will reveal additional sub-texts and for those that don’t, most are so entertaining you’ll look forward to reading them again in the future.

The last four lines of the two page Kingdome poem sneak up on you. . . and if you like how the poem seamlessly moves from being about a memorable event (the demolition of the Seattle Kingdome) into a deeper, more meaningful reflection, you’ll find at least a dozen poems that work in similar ways in this collection.

I nipped some scotch and squeezed my woman close beside me

Because we wouldn’t be around to see our own deaths, or even

One another’s and even if we did, it could never equal what we

Had just seen—this huge forever thing, no longer there.

About the reviewer:

Christopher J. Jarmick is a NorthWest-based writer and poetry activist. Writer, Poet, Author of the poetry collection: Ignition (2010); and Not Aloud (from MoonPath Press due out September 2015); Blog: http://chrisjarmick.wordpress.com/

Savage Mountain

by John Smelcer

2015

ISBN: 9781935248651

Leapfrog Press

Savage Mountain

Reviewed by Steve Barfield

Don’t look down, the craftsman John Smelcer is offering a high altitude adventure. Seeking admiration from a distant father, two teenage brothers go into the perilous wilderness throwing themselves upon a brutal and even impossible mountain. Risk is in everything and the tension propels the reader through this heart stopping tale. As amateur climbers with home-made equipment, these boys assault one of America’s highest peaks. The journey has them twice traversing the glacier at the foot of this mountain.

This in and of itself is a story of survival and almost as dangerous as the mountain. Every decision is a life and death choice as the boys test the very edges of endurance. The rigors of the climb take them up through the snowline with each step more dangerous than the last. These boys are so far from any possible rescue and entering an environment where only the best prepared will survive. The brothers even steal food from a bear. Weather is always a serious consideration. Too warm and there is the danger of avalanches. The cold has its own emphatic perils. To survive this environment and climb the boys must work as a team. Smelcer explains:

Mountaineers entrust their lives to partners and teammates a hundred times a day.

Some of the strongest and most enduring friendships are forged from having

shared the perils of mountain climbing. Some of the greatest regrets are friends

left on the mountain.

Two phenomenal sons from a dysfunctional family accomplish an impossible feat. They find from within themselves the strength to work together and eventually rediscover their lost brotherhood. The sons did all of this so that father might be proud. In the end, they found something on that mountain to offer pride for themselves. Reflected in action and dialogue these characters ring true. They are drawn from a deep understanding of people and their needs. The author does this with his own authentic-technical expertise. You will feel the chill of an artic wind blowing through his story. Upon reading Savage Mountain you will see why so many writers like this author. John Smelcer is a writer’s writer. His refined and economical style offers an easy and exciting read. For a prologue, the author compresses eons of mountain evolution into a concise short definition:

For almost a million years the mountain has been thrusting itself skyward in violent upheavals, buckling and folding the crust from the collision and one plate riding over and consuming the other, upending the very earth itself… So Insurmountable, the unconquerable mountain destroys anything that dares to rise up against it…. Some fathers are like a mountain.

The well celebrated and much honored author creates a true experience of two brothers surviving their fractured family and an unforgiving environment. Smelcer crafts a breathtaking Alaskan adventure of struggle and determined will as the boys run out of everything except pure grit.

About the reviewer:

Steve Barfield makes his living as a Medical Journalist and Editor. He is presently writing a Healthy Lifestyles newsletter for a VA hospital in Tampa Florida. Mr. Barfield is also a poet, playwright and screenwriter. His poetry has appeared internationally and has been translated into Spanish for various journals and anthologies. Author of several plays, his play “Asteroid” was produced at Towson University in Maryland. He is currently at work on his fifth screenplay. Though, he is best known as an established poet of the Immanentist style of humanist poetry.

Zygote Poems

by Richard Thomas

July 2015 . . . ISBN: 978-0-9932119-5-9

Paperback 178×127mm: 62 Pages; £5.00

Cultured Llama Press

Available at www.culturedllama.co.uk/books/zygote-poems

Review by Laura Quigley

I bought a copy of Richard Thomas’ Zygote Poems because the title reminded me of biology classes at school and I thought ‘that sounds interesting,’ and while I was waiting for my online order to arrive, I happened – by one of life’s bizarre coincidences – to catch Richard performing some poems from his book at the China House in Plymouth. And I listened, rapt, and thought, ‘Oh no – they sound too good in performance,’ because so often modern poetry sounds good aloud and yet can be painfully dry on the page.

But I finally read his collection on the bus, juggling children’s events as I so often have to do these days, now we have two offspring, and all the while I’m thinking ‘when do I get an hour to read any more?’ So I started reading in those captured ‘sunny day on the bus’ moments… and had a revelation. In print, Thomas’ work was anything but dry. The poet’s voice escapes the page, as poignant and illuminating as the discovery of a long-lost box of family photographs.

Zygote Poems tells the story of being a new father – the struggles, the humour, the semi-conscious stream of sleep-deprived exhaustion and – my favourite – the ‘Finance’, as Thomas describes the “buggered beep-beep / of the balance burnt out”. So I thought about a review, but also a little more, because Thomas’ words are part of an ongoing revolution that deserves more than just a star-rating. All social changes leave people a little broken, some more than others, as we painfully make our way to a hopefully brighter future. Modern fatherhood is no exception.

That revolution started for my family when I was born. My parents accepted the gender-defined roles of dad-at-work, mum-at-home, though in their case it would have worked just as well the other way around. When I met my partner, though, we moved in together as professional equals, and we both tried to work full-time after our daughter arrived, but child-care costs made that impossible to continue after our son came into the world. So we regressed into dad-at-work, mum-at-home. And that’s what broke him.

As a history-writer, I’ve studied photos of Victorian wives with their kids spilling out into the cobbled street, husbands aged with muck and soot from labour. I’ve seen New Delhi poor send their children to school in uniforms whiter than anything I could achieve in my chemical-devouring machine. And I wondered how they managed it.

As I endured my partner’s first nervous breakdown, nursed him through his second, sighed and tutted through his third, I felt like I was the last sane adult in a world full of dependent children. He became the doctors’ heart-sink patient, each medication failing to make him fit the antiquated male role of sole bread-winner.

And then I read Thomas’ ‘I Took Her to See Her Mother in Hospital Every Day That Weak’ – spelled ‘weak’ for good reason. It brought back gut-wrenching memories of that Co-op and that bus-stop and that “pencil-shaded outer case of Derriford Hospital”. I remembered how my partner had learned to drive just so he could get me to the hospital. How he’d gazed with joy and sadness at our new born daughter who was a miniature reproduction of his dying mother he’d said goodbye to, just weeks before. How he’d made me laugh when I was ready to burst again. All those dad and toddler walks through woods. How he kept going to work despite the side-effects of all the prescriptions, suffering nausea, headaches, fits; back at work even after a car accident nearly got him killed.

It’s hard being a modern mother, but the importance of fatherhood should not be forgotten. When my son performed his drumming for the school, I proudly sat there, and realised that although our son looked like me, the rhythms he was playing were his father’s. But his father wasn’t there to witness it. He had to be at work.

We are still struggling in the middle of this social revolution, and Thomas’ words are the miasma of it – the agonising details and the anguish, but also the pride and the hope. His poems make best sense as a collection, as a story-arc, so it is difficult to quote them out of context, but I love his near-to-closing words in ‘These Things I’ll Teach You’: “to hold your fort down at any given moment/ and come through like a champion”. I love that poem. My children’s father needs to hear it.

Highly recommended enough to make star-ratings seem a little pointless.

About the Reviewer:

Laura Quigley’s First Class BA (Hons) degree and her MA at Warwick University started her writing drama. In 2010, she won Amnesty International’s Human Rights Playwriting Award, and then Port Eliot’s Festival’s Short Comedy Playwriting Award.

She currently writes literary non-fiction books, audio plays and children’s fiction, and she’s been commissioned to produce the official book for 2020, commemorating 400 years since the Mayflower set sail from Plymouth.

About the Author:

Having graduated with a First Class Honours BA in English and Creative Writing from Plymouth University, Richard now studies an MA of the same title. Richard was shortlisted for the National Poetry Competition 2011 and his first full collection of poems, The Strangest Thank-you, was published by Cultured Llama in 2012. Richard is also an editor for Tribe.

Songs of a Dissident

by Scott Thomas Outlar

December 2015 . . . ISBN: 978-0692526460

40 Pages; $10

Songs of a Dissident

Songs of a Dissident

Review by Heath Brougher

We live in a world of man-made realities and hypocrisy, but in Scott Thomas Outlar’s Songs of a Dissident he slices right through the viscera to the bone of these falsehoods. Nobody is safe from his scathing poetic machine gun as he mows down everything from the more prominent hypocrisies to the regular Joe who does no thinking of his own while living in a world of pure materialism as is described in the poem “Pied Piper.” Outlar goes about his task with a searing brand of poetry that cuts right through convention and gives you no reason for pause when questioning the sincerity of his words. While commenting on the mainstream culture in his poem “One Foot in Front of the Other” he writes:

“What can you do when the mind-numbed masses

are like sheep led to the slaughter

who love getting fleeced

because living in the lap of ignorance’s luxury

is easier to stomach than swallowing the pill of stone cold truth?”

Songs of a Dissident is written with honor and integrity in the face of the virtually ubiquitous ignorance in which we live, and Outlar is not afraid to show how sickened he is by the way things currently operate in this world. Each poem acts as a bullet striking at the very fallacies themselves. In “Feudal Futility” he laments about how human beings have always been fighting against entrenched institutions of power in the effort to secure their freedom:

Thousands of years

of revolution and war

to throw the Kings and Queens

and Princes and Princesses

and Royal courts and henchmen

and mafia and control freaks

and psychopaths and elitists

and governments and bureaucrats

and law enforcers and pigs

and all that Divine Right hogwash

off our collective back,

and yet, still,

the mass man, the common man,

the mean man, the nothing man,

clamors for a comeback

of their oppressor.

Outlar takes no prisoners with his words, shunning any sense of shame, guilt, or blame for the sordid state of this world, as is best shown in the poem “3, 2, 1” in which he writes:

I didn’t write the Holy Verses.

I wasn’t the one

inspired by God

to lie false prophecies into the hearts of Man.

I didn’t slaughter the natives.

I didn’t enslave other races.

I didn’t stomp on Pagan grounds.

I didn’t erect churches

atop conquered lands.

I didn’t start the wars.

I don’t need to finish the job

that other animals began.

One must remember, though, that Outlar’s honesty must never be mistaken for apathy. These poems are written from the standpoint of a downtrodden idealist whose flame, although almost smothered, is still flickering and alive. There are occasional moments of hope for the future envisioned in the form of an oncoming awakening for all Mankind. “Artificial Dye,” the final poem of the book, is the most straightforward of these glimpses. While speaking of the possibilities that still remain within the grasp of the species Outlar writes:

It will be a Revelation.

It will be a Renaissance.

It will be a Revolution.

It will be a fire of Apocalyptic fervor.

It will be a truth made manifest.

It will be a destiny delivered in full.

It will be a New Age.

This is an important ending. It shows that the other scathing poems might be detailing how things currently reside on earth, but that the path going forward can still be redirected should Mankind make the collective choice to rise up out of the ashes and develop for itself a stronger and more humane consciousness. Songs of a Dissident speaks the truth in droves. Although it is the length of a regular chapbook, it is written with a wide breadth which covers many subjects and so it reads as if it were a full-length collection. I believe it to be the first step in Outlar’s aforementioned Renaissance. The flickering flame of Idealism espoused within the pages has the potential to intensify and spread into one hell of a blaze.

About the Author:

Scott Thomas Outlar hosts the site 17Numa.wordpress.com where more about his published work can be found. He is a proud member of The Southern Collective Experience; he also serves as an editor at Walking Is Still Honest Press and The Peregrine Muse. His full-length poetry collection “Happy Hour Hallelujah” is forthcoming in 2016 through CTU Publishing.

About the Reviewer:

Heath Brougher is the poetry editor of Five 2 One Magazine. He has published two pamphlets with Green Panda Press. His work has appeared or is forthcoming in Yellow Chair Review, Chiron Review, SLAB, Main Street Rag, Diverse Voices Quarterly, Mobius, Of/with, eFiction India, and elsewhere.

F– USE

by Bina Sarkar Ellias

ISBN #978-93-82749-22-6)

(© 2015: Hardbound: $16.00)

Poetry Primero, an imprint of Paperwall Media & Publishing Pvt Ltd

(Mumbai, India)

When Words Tear the Curtains to Unleash Trapped Reality

When Words Tear the Curtains to Unleash Trapped Reality

Review by Blaire R. Ferry

F— USE by Bina Sarkar Ellias is an incredible collection of poetry that focuses on a variety of subjects with a specific focus on the condition of the human race.

The book opens with an introduction. While people often overlook introductions, this particular intro is not one to be skipped. Written by Alan Britt*, an American Poet and Professor at Towson University, the introduction provides the reader with a glimpse inside the poet’s head. Britt explains, in the introduction, that Ellias’ work is meant to reach out and direct humanity towards helping one another. He reflects that her poetry touches not only on difficult issues but also on the way to fix the problems, all for the cause of bettering our world as a whole. Britt points out the common themes in Ellias’ poetry, such as the struggles of war and the ugliness the world faces on a constant basis. He speaks of the passion Ellias puts into her poems. Her love for friends and family, her strength in her faith, and her determination towards bettering the world all play a key element in her beautiful poetry. Likewise, Britt’s introduction focuses on Ellias’ precise diction. Britt explains that Ellias uses “language as the primary vehicle for clarifying perception” and he insists above all that her poems “assert that hope exists.”

After Britt’s intro, the book progresses to short reviews on the poems followed by a small forward written by the author herself. The reviews, which speak highly of the poems, indicate that Ellias “experiences a moment, visualizes that thought, and then expresses it in words.” The reviews also speak to her mannerisms of writing and glorify her work by claiming that the poems are “poems of light that uplift that soul.”

After such praise, Ellias adds a quip of humble humor, addressing her work as “These scribbles.” She speaks on her first experiences of writing verse, her poetic experience starting in grade school, and continues with grateful thanks to friends, family, colleagues, publishers, and others who helped her along the way. Her final thought is a touching thanks to her spouse of forty-two years before the book begins with the first poem, “Scavenger.”

One moves into the poems at this point and is quickly drawn headfirst into them, which is the best way to appreciate their power. The gravity of the work is not crushing, nor are Ellias’ poems so complex that one must read them six times over; however, the work is mind expanding. One listens to the work beyond a silent reading of the poems because Ellias’ writing invokes the senses allowing readers to experience significant moments. Her word choice like “throbbed/ to the pulse // of remedies / and potions // that cure / the body // but not / the soul” allow the reader to hear the throbs and hear the clinks of moments she describes. Sometimes the brevity of these poems makes one wonder how Ellias could possibly write such descriptive and thought-provoking work with so few words. Her use of description is immaculate from poem to poem, and her topics of interest circle the globe while moving across the pages.

Ellias offers the reader a presence of harmony and peace with her style. There is no aggression in her tone or her speak. The beauty of her poetry is recognized by the introductory reviews. Passages such as “fall with it- / fall with time; / living each moment / with pure imperfection // and in truth to yourself” cause readers to feel the invitations she offers in her work. Ellias personifies abstract ideas, such as night and day, through simplistic yet wonderful imagery: “i ripped open / the night // to reveal / it’s dark secrets // and found / day slouching / in a corner.”

All in all, the poems in F– USE are written with a precision and passion that readers are easily able to access. Bina Sarkar Ellias inspires a mindset that embraces the world to change by looking at reality in a new light. Her imagery is simple yet holds a complex nature that flows softly through her poems. Her work follows no rigid pattern, but that is the most beautiful part about this collection of poems. The read is worth every moment. Simply put, F– USE is a skillfully crafted and delightful book that rewards its readers with poignant intelligence through language that is imaginative and profoundly engaging.

About the reviewer:

Blaire R. Ferry is pursuing her English degree on the writing track at Towson University. Writing since age five, she finds no greater joy in life than creating worlds through words. Originally from Maryland, she currently lives in New Mexico.

* (Alan Britt is the book review editor of Ragazine.CC.)

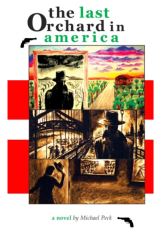

The Last Orchard in America

by Michael Peck

186 pages, $12.00 ($7.99 Kindle edition)

The Last Orchard in America

Review by Denton Loving

In Michael Peck’s first novel, The Last Orchard in America, down-on-his-luck private eye Harry Jome is ensnared in a mystery within a mystery. Though Jome narrates his own story, driving the drama is Sue Longtree with brilliant red hair and a penchant for doling out information on an as needed basis. She was “a slightly attractive, narrow-faced woman of around 35 or 40. Big dark sunglasses covered what were purportedly her eyes. In profile she had slightly masculine features that lend themselves to women of a particular attitude, and she certainly had that attitude.” In other words, Sue Longtree “was nuts, but she wore it well.”

She hires Jome to investigate the death of her brother, an apparent suicide in a family tree blooming with suicides and murders. Sue’s motivation, she tells Jome, is to search for evidence of some errant genetic trait that will hit her next.

In recounting her family history, Jome says, “It was a crazy story that included disappearances, reappearances of key figures, darkness and havoc,” which is an apt way to describe The Last Orchard in America. In fact, Peck uses this metafictional device throughout the novel to comment on this particular detective story and the whole genre of black-hearted noir.

In most cases, this device works, though Jome reminds us that “saying something dumb isn’t the same as wit,” which is proven in some of Jome’s interrogations that come across more as parody of the genre. It seems nobody in this twisted city, where it happens to never stop raining, knows how to give a straight answer. That complicates matters as the number of detectives start to multiply. As busy as Harry Jome is, he’s constantly being followed and harassed by a series of private eyes, each more inept than the last.

About half-way through the narrative, witness interrogations are outweighed by a faster-paced plot and significant danger at every turn. As Jome and Sue Longtree grow closer, their relationship becomes more dangerous. Jome’s investigation leads outside of this bleak city and into an even darker, more gothic countryside, thus leading to the Longtree family orchard. Ironically, as the bodies begin to pile up, the reader feels more entrenched in this world. Trying to unravel this mystery and to understand “who done it” will leave readers appreciating Peck’s precision in his language and plotting, as well as the novel’s layer upon layer of complexity.

The Last Orchard in America was originally serialized by THE2NDHAND (the broadsheet founded in Chicago in 2000 and now also online as THE2NDHAND txt). Funds for publication were raised through a Kickstarter campaign.

About the author:

Though The Last Orchard in America is Michael Peck’s first novel, his fiction, essays and reviews have been featured in The Believer, The LA Review of Books, Icon, Juked, 34th Parallel Magazine, Eclectica and [PANK]. Born and raised in upstate New York, Peck currently lives in Oregon City, Oregon, where he deals in rare books when he isn’t writing.

About the reviewer:

Denton Loving is the author of the poetry collection, Crimes Against Birds (Main Street Rag, 2014), and editor of Seeking Its Own Level, an anthology of writings about water (MotesBooks, 2014). Follow him on twitter @DentonLoving.

Recent Comments