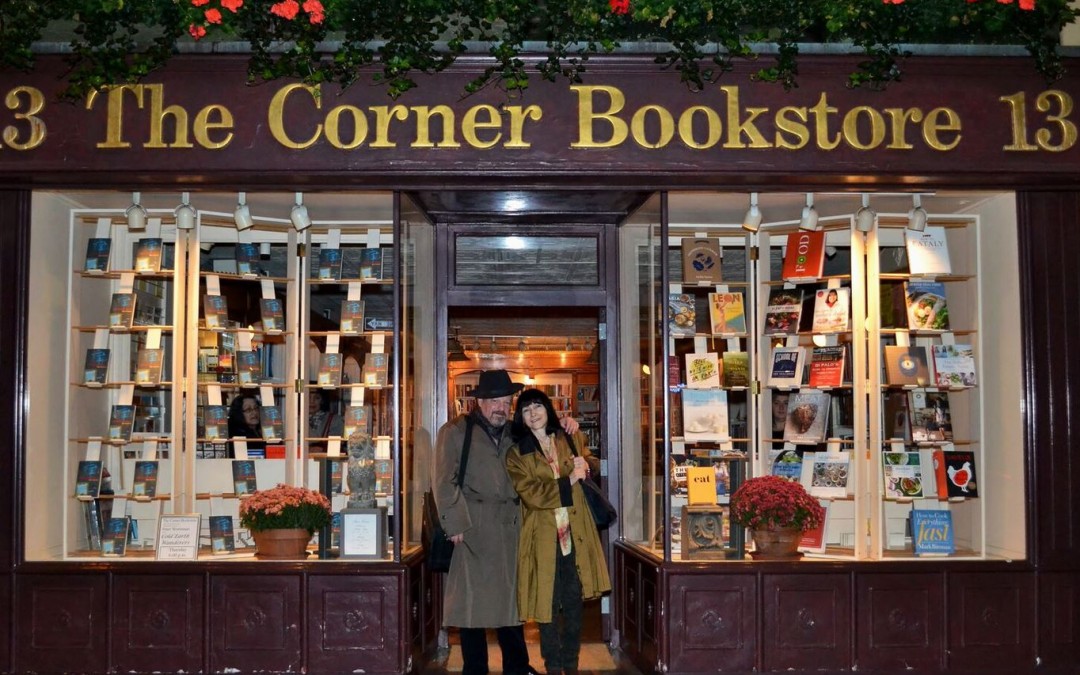

RICKY OWENS PHOTO

The author and his wife at the book launch of his novel Cold Earth Wanderers at The Corner Bookstore, November 2014.

* * *

* * *

Where Have All the Bookstores Gone?

* * *

New York City’s Independent Booksellers —

* * *

Endangered Species or Phoenix on the Rise?

*

* *

By Peter Wortsman

Once upon a time in New York City bookstores mattered. The shingle “Wise Men Fish Here” dangling above the doorway of the Gotham Bookmart, on West 47th Street, in the heart of the Diamond District, said it all with a tongue-in-cheek tease at the gaudy glitz of its surroundings. Rents were low, poets were hip. Bookstores were the place to be. But nowadays those depots of wisdom, where word-junkies like myself have long dashed in for a quick fix of fact and fancy, merit endangered species status. Real estate has a limited tolerance for the tenuous fruits of the unreal estate. Raging like a tornado, commercial rent has taken its toll. Gone are Doubleday’s and Scribner’s, once proud Fifth Avenue literary landmarks, and Mary S. Rosenberg, the foreign book dealer on Broadway, where you could hope to find Max und Moritz in German and Babar in French. Books & Co., an Upper Eastside browser’s paradise for more than two decades, closed in 1997. The Gotham Bookmart bit the dust in 2007. That same year Coliseum Books, the Midtown independent, likewise shut its doors. And as of this writing, the hipster paradise, St. Marks Bookshop, is holding on by the paper of its book jackets.

The first bookshop in New York City founded by printer William Bradford opened for business in 1693. One of his apprentices, John Peter Zenger, opened the second in 1742. Bookstores began to proliferate here in the wake of the American Revolution. The back room of one such shop at 167 Broadway, dubbed The Den, became the hangout of poet and journalist William Cullen Bryant, painter and inventor Samuel F. B. Morse (of telegraph and “Morse” code fame), and novelist James Fennimore Cooper (you know, The Last of the Mohicans). In 1853 an enterprising Austrian immigrant, August Brentano, expanded his newsstand into Brentano’s Literary Emporium, the clubhouse of writers Henry Ward Beecher and Edwin Booth. Brentano’s subsequently spawned a chain of stores, successively gobbled up by Waldenbooks and Borders, which subsequently went belly up. In 1917 William Barnes and G. Clifford Noble launched a bookselling business, later shifting their location to 105 Fifth Avenue, the future flagship store of Barnes & Noble, a veritable empire of books, itself presently suffering from competition from Amazon and other online virtual venues.

A native New Yorker of bookish bent, my own bibliophile infatuation predates my ability to read. There was a rack of illustrated golden books in the back of a toy store with the magical name of Aladdin’s Lamp in Jackson Heights, Queens, where I grew up. Whenever I fell ill and had to undergo the prick of Dr. Goldberg’s needle, my sufferings were recompensed by a golden book. I can trace my conversion to “bookoholic” back to an adolescent fever, circa 1966, when, on the way home from the doctor, at a drugstore that also carried a couple of books, I plucked off the rack a purple paperback copy of Lady Chatterly’s Lover, which may not have stilled the fever but definitely mollified my malaise under the covers.

Bookstores have always been for me the loci of revelations.

I once walked into the old Eighth Street Bookshop, erstwhile clubhouse of the Beats, on Eighth Street in Greenwich Village. Hastily pulling off the shelf what I believed to be poems by Stephen Crane, when I got home I found, to my initial chagrin and eternal delight, that I had mistakenly purchased a volume of verse by Hart Crane, one of which, “Van Winkle,” struck a chord that set the tone of my life:

“And Rip forgot the office hours,

and he forgot the pay;

Van Winkle sweeps a tenement

way down on Avenue A.”

Such a felicitous mistake would never have transpired on Amazon. The Eighth Street Bookshop went up in flames one night in 1979. The circumstances of the fire have never been established. Much as I mourned its loss, I managed to fish out and schlep home several hundred blackened, but still readable, tomes from a massive garbage bin parked outside on the street, and later wrote up and published my experience of inviting passing patrons to climb in and browse.

It was in the claustrophobic confines of another long gone little downtown book nook on East 7th Street named The Bridge, in homage to a book of poetry by Hart Crane, that I read from my English translation of Posthumous Papers of a Living Author (Nachlaß zu Lebzeiten) by Robert Musil, to a standing room crowd. I must have fired them up, for two audience members almost came to blows afterwards arguing over the title of the first published Yiddish book. It’s hard to imagine such a hot dispute taking place at Barnes & Noble.

And how can I ever forget the tingling pride I felt a few years later upon seeing my own first book of fiction A Modern Way to Die, in the window of The St. Mark’s Bookstore, the ultimate downtown literary hotspot. I felt like I had finally arrived, though I would subsequently be disabused of any such naïve illusion. In New York, subway trains arrive, writers go nowhere.

Given rent negotiations underway at the time of this writing with their landlord, Cooper Union, the staff at St. Mark’s Bookshop, were reluctant to talk about the prospects of survival. Cool is the rule. Previously located around the block on St. Marks Place, the store has held literary court since 1977. A downtown denizen herself, Margarita Shalina, the small press buyer for ten years and counting, remains adamant about the need for independent bookstores like St. Marks: “We just had this crazy storm in New York, right, and we stayed open all weekend. I noticed everyone was buying up these thousand page tomes, The Power Brokers and Anna Karenina, and I’m like, oh, they’re afraid their lights are going to go out and they’re not going to have internet or TV. They’re going analog. When the lights are about to go out, people remember books.” Cooper Union since agreed to lower the rent, granting St. Mark’s a temporary reprieve. Shortly thereafter they moved to a new location at 136 East Third Street.

“We’re open!” Toby Cox, proprietor of Three Lives & Company, a West Village institution since 1978, located at 154 West 10th Street, calls out to a hesitant customer the morning of a hurricane. Huddled in the shell of a former grocery store, its bookshelves lend the illusion of safety from the storm. Tall, bald and beaming, like a human lighthouse, Toby’s warm smile flashes welcome. “This is a place to climb off the fast track, a place to connect and celebrate the unique connection between two people, the writer and the reader. It helps,” he adds, “to have a sympathetic landlord.” Though Amazon has siphoned off business, price is not the key consideration for his customers. “I have one regular, a lawyer who loves books, who brings us prosciutto and cheese every Saturday. His daughter, who practically grew up here, dropped by yesterday to give me a hug before going off to college. Maybe I’m a simple man—I am a simple man!—but that kind of thing makes all the difference.”

“Most people have small apartments. It’s nice to have a place to come to.” This is the secret of their survival, according to Stephanie Valdez, co-owner with Ezra Goldstein, of The Community Bookstore, at 143 Seventh Avenue, in Park Slope, the oldest (and most congenial) independent bookstore in Brooklyn, founded in 1971. Rising rent is a concern. But Valdez and Goldstein see their best bet in keeping the shelves well stocked. They tend their shelves like loving gardeners familiar with every flower. “A half hour ago,” says Goldstein, “a man came in and said: ‘I know this is a stretch, and you’re going to have to order it for me, but do you have any James Fennimore Cooper?’ ‘Yeah,’ I said, ‘we have a couple.’ He said, ‘I’m looking for a really obscure one called The Pioneers,’ ‘I’m sure you don’t have it.’ I said, ‘Let’s look.’ And I went back and pulled the book off the shelf. He said, ‘You’re amazing!’”

“So are books a luxury or a necessity?”

Goldstein hesitates. “I’m constantly amazed at the number of people who say they need a certain book because of a mood they’re in or something they’re going through. Yes, I think they’re a necessity. Sure, we could live without books, but our life would be sadly diminished.”

By any accounting of new independent bookstores in Brooklyn, Greenlight Books, in Fort Greene, heads the list of success stories. Nestled in spacious digs in a refurbished warehouse at 686 Fulton Street, in this ethnically and cultural diverse neighborhood, not far from BAM (The Brooklyn Academy of Music), the store looks as if it might have been lifted whole, polished parquet floor, pinewood shelves and all, from a New England college town and dropped in the urban grid of downtown Brooklyn. “For me,” says Jessica Stockton Bagnulo, co-owner with Rebecca Fitting, “it’s all about making a beautiful space out of and for books, and for people to enjoy them.” Ever since opening its doors in 2009, business has been booming. “We keep exceeding our own expectations,” beams Jessica, a natural born bookseller with rosy cheeks and bright eyes straight off a children’s book jacket. She relates the store’s success to the “Buy Local” movement in food. “This community was hungry for a bookstore. Fort Greene’s got a lot of young families and we have a rich children’s collection. And there’s a very vibrant African-American community, so we try to represent that throughout all the sections of the store.” Jessica adamantly debunks the myth of the death of the bookstore. “When a restaurant closes, you think, they had a bad chef. But when a bookstore closes, the word is that people don’t read anymore. But there are as many reasons why a bookstore closes or thrives as there are bookstores.” A few years back Greenlight signed a partnership with BAM to sell books at kiosks at all events.

Other recent arrivals in the Brooklyn bookstore boom include Word in Greenpoint, Unnamable Books in Prospect Heights, Boulevard Books in Dyker Heights, PowerHouse Arena and Melville House in Dumbo, and Spoonbill & Sugartown Booksellers in Williamsburg.

The prognosis for the future is mixed in Uptown Manhattan. Among the last of the independents on the Upper West Side is Book Culture, at 536 West 112th, around the corner from the gates of Columbia University and down the block from the Cathedral of St. John the Divine. The store has long leaned to the scholarly, but the academic book business is in a slump, given the dwindling number of students applying to and pursuing Ph.D.s in the humanities. In business since 1997, owner Chris Doeblin decided to diversify. In 2009 he opened a new store, Book Culture on Broadway, that also carries “non-book,” i.e. scarves, toys, and knickknacks, along with more popular titles. But sales in the main store are declining. Doeblin ascribes the sorry state of affairs at least in part to an industry at odds with itself. “When publishers agree to sell to wholesalers like Wallmart, Cosco and Amazon at or below cost,” he insists, “it’s destructive, not only to themselves and to the business, but to our entire culture. They need us more than they know.” According to Doeblin, though independent bookstores only account for an estimated six to seven per cent of the estimated total $857 million of annual book sale revenues nationally, “we still wield considerable clout among the reading public.”

A buzz begun in an independent bookstore can carry a little known title to victory in a prestigious competition, bringing it mass market appeal. Such was the case when a book launch, spiked with whiskey and Irish pipers, at The Corner Bookstore, at 1313 Madison Avenue, helped spread the word for Angela’s Ashes, the 1996 memoir by the late Frank McCourt that went on to win a Pulitzer Prize and a National Book Critics Circle Award. A marriage of elegance and intellect, the store, run by Hélène (aka Lenny) Golay and her husband Ray Sherman, is either a throw-back to another era or a harbinger of things to come. Toward the end of a working day one is greeted by the unlikely sight of young men in business suits bent over the browsing table, wheeling baby carriages and with a book-loving toddler in toe leafing at knee-level. The fact that Lenny and Ray, who opened for business in 1978, bought the building for a pittance, live upstairs, and so, pay no rent, is a key factor in the store’s survival. That and the selection. Lenny chuckles: “I remember a woman once walking in with a friend and remarking, ‘Oh, I hate coming here, because every book I see I want to buy!’”

For close to two decades, from its launch in 1978 to its much mourned demise in 1997, Books & Co., at 939 Madison Avenue, next door to the Whitney Museum, was the walk-in literary salon of the Upper East Side, lovingly tended by its owner and resident muse Jeanette Watson. “It had to look the way it did in my dream: cozy, comfortable, lived in,” she recalled in a conversation over coffee. In the late Seventies bookstores could still be a glamorous locale. Regulars included the likes of Jackie Kennedy Onassis, Truman Capote, John F. Kennedy Jr., Edward Albee, and Woody Allen. Jeanette remembers conversations. Like the time Carlos Fuentes confessed to her young son one Halloween: “Not only do I believe in ghosts, I write books about them!” Or Truman Capote’s regret upon learning that Lee Radziwell’s latest wedding plans were a wash: “I wonder if I can get my present back!” And poet James Merrill’s Christmas list: “I’m buying books for my fat friends and food for the thin ones.” “My biggest mistake,” Jeanette confesses, “is not having followed my father’s advice to buy the building.” The party ended when the Whitney, that bought up the block, raised the rent beyond what the bookstore’s revenues could generate.

The most independent bookseller I know in New York prefers not to be identified by name and location. Rent is not an issue. His roof is the sky. His walls are virtual. His shop consists of several folding tables, with boards stretched between them, pitched like a nomad’s tent outside one of the city’s major universities. As a young man he read hundreds of books. “I’m not so attached to books per se these days,” he insists. “It’s the content that counts, and the effect they have up here,” he taps his head, “and here,” he taps his heart. “Still, there is something very deep in humans that books can potentially develop. I say potentially. Germany was the most educated and well-read country in Europe. It obviously didn’t do them much good.”

Embattled bastions perhaps, but New York’s independent bookstores still seem to serve a need. Consider Mercer Street Books and Records, at 206 Mercer Street, a trading post of sorts for second-hand books and records. “It’s one of the few places I can imagine working,” says store manager Chris Sholk with a deadpan Buster Keaton look, “where Schopenhauer could be the punch line to a joke, and somebody will actually get it and laugh. There’s never a dull moment. Just yesterday a young lady in her early twenties came in and said, ‘Here! Take my books, I’m moving to Berlin.”

A very well-written and interesting article Peter. This needs to be read for an audience. Probably the same audience that has spent very little–if any–time in a bookstore.

No mention of East-West Books, on St. Mark’s Place off 2nd Ave, where in the 70’s I passed out my poetry pamphlets for free and there was a plethora of great lit mags, like Kayak? Gone, but not forgotten.