SHADES OF DISQUIET

Artist Linda Ternoir Interviewed

by Toti O’Brien

Contributor

Years ago I had the pleasure of sharing an exhibit with artist Linda Ternoir. As we both sat the gallery, conversation sparkled naturally. I immediately realized I had met not just an awesome creator, but also a woman of great depth and lightness. Clearly, she had thought at length about themes I cared for — inspiration and craft, art and its intersections with life, community, identity. But her wisdom came wrapped within nonchalant grace and genuine humility. I wished she and I could maintain an on-going dialogue.

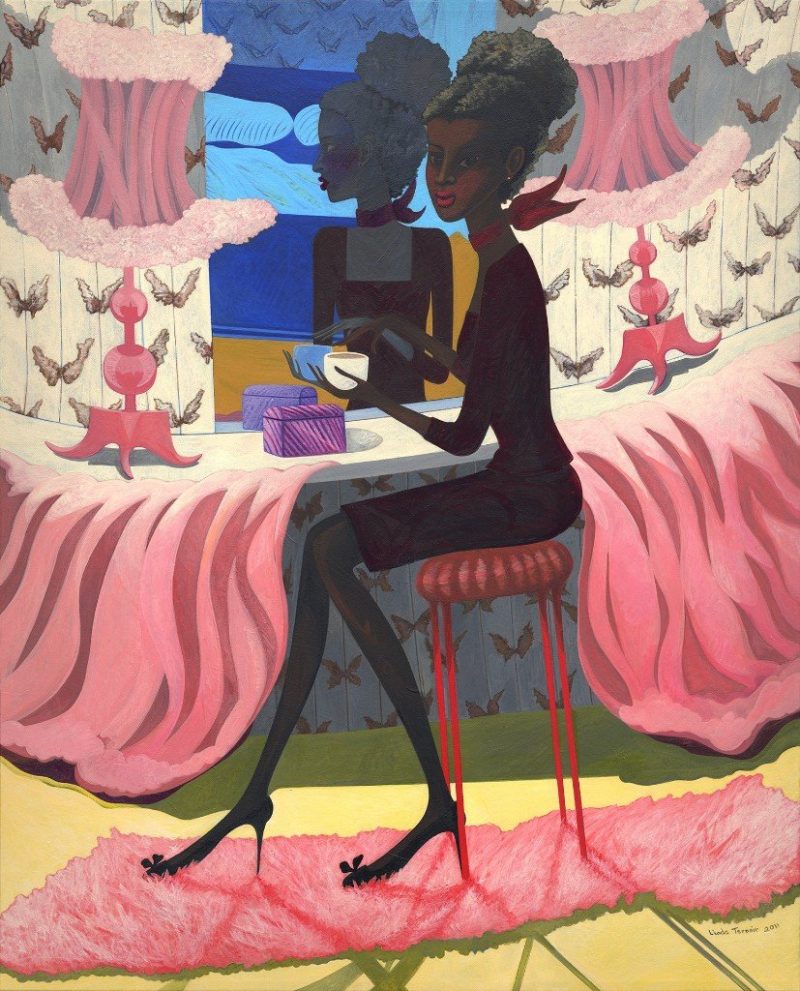

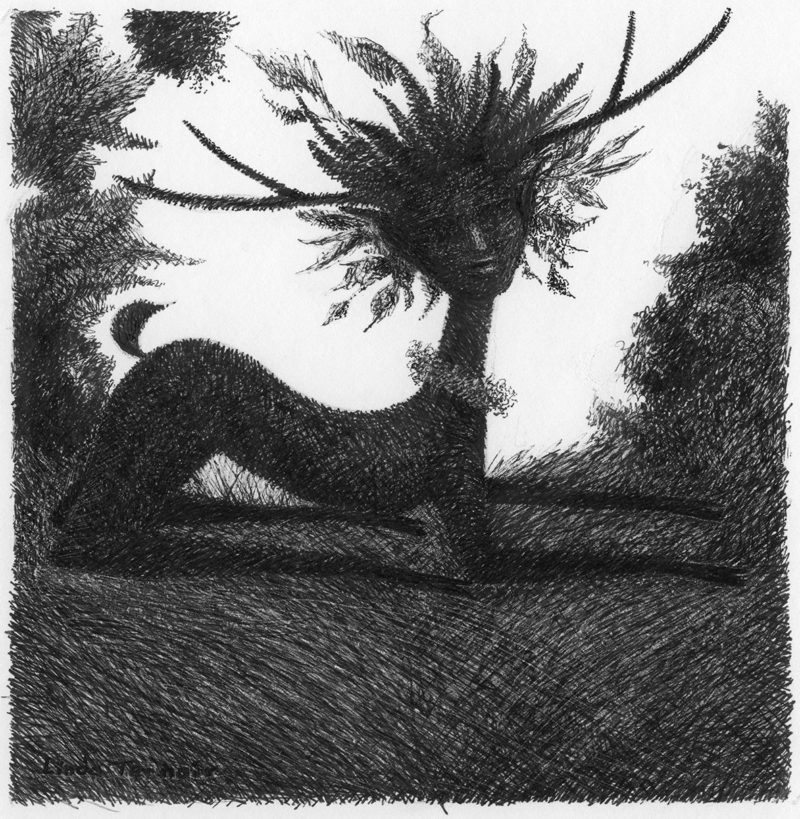

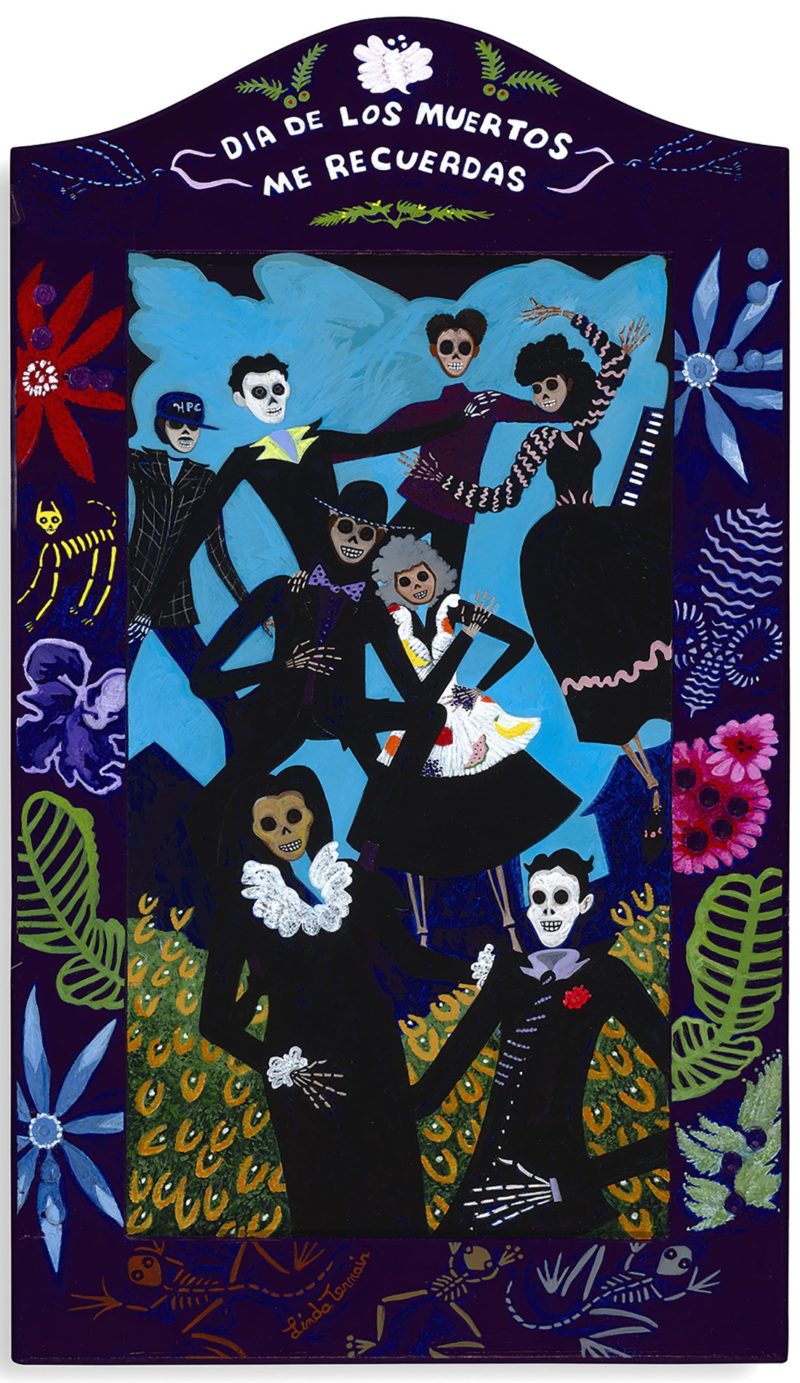

Ternoir essentially works in two media. She creates large, colorful acrylic paintings and small black-and-white ink drawings. Side by side, these techniques generate an interesting contrast. Yet they have lots in common. Both are figurative and narrative. In both, figure and landscape are treated fluidly and freely. Both convey a sense of mystery, though achieved with different means. In the paintings, the enigma is conjured by the scene portrayed — who is there, who is doing what and where — and by the choice of color — luscious, festive, but endowed with a touch of strangeness and a subtle disquiet. In the drawings, mystery is created by complex textures of dark somehow blurring the figures, hiding shadows or ghosts, summoning the viewer to come close, explore, wonder.

It takes her very long, Linda says, to complete a painting. If she weren’t so slow…

Toti O’Brien: Why do you think you are (a slow painter)?

Linda Ternoir: I am thorough. I think about things that pass other people by, things that people don’t notice.

TO: Have you been so observant since when you were a child?

LT: I recall being observant since when I have memory. I think all children are. After all, attention is their survival tool. They can’t communicate as adults do. They make up for it by being alert, knowing when to do what, for how long, who with. Because my childhood was so non-nurturing, I had to be more acute.

TO: How was your childhood non-nurturing?

LT: It was anti-nurturing! Barren.

TO: Is it why you were more aware than average, hyper-vigilant?

LT: You become hyper-vigilant when you perceive danger. Kids who are appreciated and loved feel secure. Kids who aren’t — which happens a lot — build antennae. They need to foresee where the next problem will come from, know whom they can trust. Trust is crucial! If you are waiting for the next blow, then your trust is gone.

TO: So you date your gift of observance early in time. Could you have become an artist, then, by creatively applying those skills you had precociously honed?

LT: I am not sure. To stay alive is our most basic impulse. But if we remain at that level we can’t grow as we should. We perpetually worry about not being hurt either physically or psychologically. Children cannot put these things into words, yet they feel them. Perhaps not all children have the same acuity, but my observation of kids — I worked with them a lot — is that most have a sense of preservation. If such need is met they can go to the next level. If they feel afraid, they can’t.

TO: But you did! You weren’t in a situation so bad that it kept you stuck. You moved forward…

LT: True, my spirit wasn’t killed. But it had to hide itself, because it was violated.

TO: By whom?

LT: By every fucking body. My grandfather molested me sexually. My grandmother was vicious and mean. She hit me across the back with a razor strap, and she locked me in a closet. My mom was very cold and she didn’t like me. My dad was an absentee. So my house was full of anti-nurturing people. I feel that who-I-really-am is coming out now for the first time, at my oldest age. I am not ‘fully realized’ of course, but I feel, ‘Ok! So this is the start of what could have begun seventy years ago.’ But I was busy trying to stay alive! I could not give to my creative side the care it deserved.

TO: And yet you’ve been an artist for much of your life!

LT: I wasn’t completely shut down. I could be thirty percent creative sometimes… maybe forty percent. But I have seen children so safe with their parents that they could unfold one hundred percent.

TO: Do you regret that not being your case?

LT: I cannot regret it, because I see myself as a world citizen. In order to pity myself I would have to entirely ignore my surroundings. I am so fortunate! Many people, plants, animals, have a really hard time. I can’t even think about how they suffer. My heart bleeds every day for the injustice that occurs around me. Had I been a ‘fully accomplished’ person, I still couldn’t have said, ‘I’m happy and who cares about them!’ So I enjoy what I have… and I carry this sadness about what goes on in the world.

TO: So your consciousness of the pain of others makes your own life acceptable.

LT: Even though I had a nasty upbringing and some bad things happened, I am alive. I have all of my limbs. My brain functions as far as I know. I have so many things I can work with. Yes, I am grateful.

TO: When did you begin making art?

LT: I don’t recall the first time, but I do remember an episode that took place during fourth grade. One day I did a drawing with crayons, and I consciously decided to use the colors no one would think of using. Most kids choose red, green, light blue… I chose purple, brown, black, dark blue, and the teacher went, “Look at these colors!” It was as if she had given me a ton of gold, as if she had yelled, ‘I love Linda!’ I had been drawing already for a long time, but that incident remained truly impressed. It was wonderful that someone could react so well to my work!

TO: Why did you employ ‘unusual’ colors?

LT: I am trying to recall that moment… It was simply a thought… ‘why don’t you do that?’

TO: It was an inspiration!

LT: I had figured what colors other kids would use—what I ‘normally’ would use— and I thought, ‘let’s try something else with this one!’

TO: Do you know what the subject was?

LT: It was complex. People in a situation, in a room…

TO: That is what you have done since! People in situations! Did you cling to art, perhaps, because you had such positive feedback?

LT: I did not. I have understood only now how low my self-esteem was at the time. I couldn’t even have thought, ‘I am going to do this because it will bring me positive feedback’. I could not have gotten that far. That was a great moment for me, but rare — isolated within an atmosphere of constant belittlement on behalf of the Catholic nuns, and more hurt at home. There was no refuge for me if not in my dreams. I couldn’t wait to go to sleep! In my dreams I was soaring and free. My life wasn’t all dim and horrible, because I had a sense of humor. I knew how to enjoy things. I knew how to laugh. And, absurd as it sounds, TV saved my five-year-old life. People say how bad television is, but hey! Buster Crab, Flash Gordon… Bursts of energy flooded my mind as I watched. That was creativity!

TO: I can see a link between dreams, TV, and art. Did you read?

LT: As I got older, a lot.

TO: Could you please remind me of when you were denied storytelling, in school? Every artwork of yours tells a story. That’s what ‘people in situations’ means! You exquisitely narrate in painting and drawing… Would you have liked to do it in words?

LT: I was young. On the playground of the Catholic school I was ostracized. My schoolmates called me ‘Turner Germs’. See, the nuns had switched my name into ‘Turner’. For them, ‘Ternoir’ held the painful possibility that some of my ancestors weren’t enslaved Black. The kids picked it and added the word ‘germs’, meaning that I was malignant and should be avoided. No child of my age played with me, so I started telling stories to the young ones. There would be perhaps thirty of them sitting down and listening. Words came through me. I heard the stories inside me as I told them, and they were good stories — exciting, adventurous. I remember the kids yelling, “Don’t stop!” Once, the head nun stood behind me and she watched. She must have felt that something was wrong with so many kids sitting and listening. My stories weren’t salacious or dirty — just adventurous stuff — but they had power, and that must have sounded evil or sinful… Now I am putting thoughts in the nun’s mind — but her posture, her tone, her face and her eyes conveyed it all. She stared straight at me and said: “Don’t tell any more stories,” with a threatening tone. And I stopped.

TO: Five years old?

LT: Six or seven. While at eight, as I was drawing in my classroom, I didn’t have any crowd. I didn’t impact other kids, so the teacher — who was a lay substitute — could simply appreciate my work.

TO: You weren’t forbidden the art making, but you were the storytelling. Did you internalize the interdiction?

LT: I didn’t. She shut me down.

TO: For the rest of your life?

LT: Storytelling never went away. I wrote and read stories. I just didn’t for a while, because I had been punished — at least psychologically.

TO: But you made painted narratives in the meantime…

How do you alternate between drawing and painting? Is there a particular rhythm? What causes you to choose a specific medium?

LT: I get visions, and they come in specific forms… a painting, a drawing. They are powerful images that I feel compelled to realize. When the vision is strong, the art is usually good. I can make things up, invent subjects and scenes, but I’d rather listen to what spontaneously emerges. Following my impulse makes the work inspired and ‘pure’. To me, art is beautiful and enduring when it comes through that particular channel.

TO: I wonder if its ‘pure’ origin is what gives your art such great freedom. In your composition — line, shapes — there is such flow, such lightness… Everything is dancing or flying.

LT: This trait has emerged as part of my style. I feel strongly about freeing individuals to be whoever they are, to be unshackled. There is a concerted effort, in this country — perhaps in the entire world — to impede such freedom. Many people can’t really express who they are for fear of being criticized or shut down. There are predators too, who see you as a free person and try to sabotage you by all means.

TO: Why?

LT: They identify someone who exhibits some kind of freedom and they want to repress it. They are small-minded. Perhaps they feel threatened. I have learned to recognize these people. Being an artist and being open, though, I am often taken off guard.

TO: Why do you connect being open — therefore vulnerable to ‘freedom predators’ — with being an artist?

LT: We have just talked of visions… of that special channel, that genuine source… One of the tools I have as an artist is to be open to stimulation, experiences and emotions. The more open I am, the more comes through and the more I can work with. The more closed I am — in order to block negative or hurtful feelings — the more I cut off my sources. I could shut down, shield myself, and I still could work. As I said, I can make up subjects and scenes. But I’d rather stay open and feel the pain, because that’s the same portal through which inspiration and beauty come — the things that make me want to make art.

TO: So your art is made of your feelings, insights, understanding. It is nurtured by beauty and also by pain. By allowing yourself to feel about other people, to be affected by them… By being permeable. And vulnerable.

I would like to explore the connections you make between art and race.

LT: Do you have a few hours to spare? Should I start from the beginning? I came into this world like any other child, wanting to experience the wonderful things that life is about. But I soon started to hear words like ‘Colored’ or ‘Negro’ and I had to adjust to those labels, as well as to the treatment that came along. I understood the do’s and don’t’s that restricted the ‘Colored’ as I listened to conversations among the adults who raised me — until the age of nine, primarily my mom and my maternal grandmother. When I was about five years old, for instance, riding the streetcar from downtown Chicago, I vomited on the raincoat of a White man. I was so conscious of unspoken taboo that I was surprised when the man gently said, “That’s alright.” When we got home, I heard my grandma relating the story to my mother. At the end she lowered her voice to a whisper: “And he was a White man!” I remember this vividly, because it told me just what I needed to know about looking the way I do, in the White world. We lived in a ‘Colored’ middle-class neighborhood, one block south of the ‘projects’. My maternal grandfather lived in more of a ‘ghetto’ area, so I was familiar with that type of reality. But my dad had a totally different experience. He was so light-skinned that Black and White people considered him to be White, and treated him accordingly. So I gathered both a complex and a nuanced legacy.

Here is an episode that can show you some of the nuances. Once I was on my bicycle, trying to get across the street before a bus turned. The driver just came at me. She almost hit me. The entire bus screamed, thinking that she had. As I related the incident to a friend, he asked, “Was the driver very dark?” “Yes!” “Well…” “Well what?” I hadn’t yet understood that my lighter skin, inherited by my father… The driver thought I was privileged and I might have been, you know? I don’t know how I would have lived if I had been darker. And she was very dark.

TO: Would you call such behavior ‘racism’?

LT: Of course not, because she and I belonged to the same race. It is a by-product of racism. Have you ever read The Letter? It was written in the 1800s, and it was a guide about how slaveholders could keep enslaved people subservient. ‘Pit the light against the dark.’ A list of tricks followed about pitting slaves against slaves. ‘The house slave against the field slave.’ House slaves were often lighter, because they might have a White father. Fields slaves only got darker because they were out in the sun. There was a whole hierarchy… Years ago I watched a documentary about color in India, South America, America, and in every single context the parents said to their children, ‘Marry as light as you can to improve the race’. Well, that has endured. It is powerful and it is destructive.

TO: How does this concern show into your art?

LT: When I was much younger I consciously started to portray Black people living their lives. The over-emphasis on art by and about White people creates the impetus to do art about Black people in order to offset the unbalance, break the mold. Also, in order to counter ignorance… I remember something that happened years ago. I had a painting in a show and a White boy came by, looked and said, “I know! First you were enslaved…” In my painting there were a woman in bed and people around a table, but his mind immediately went to the theme of slavery — it was shackled to that theme. Yet he only saw people doing normal things like sleeping, eating, talking…

TO: Are you saying that most White people have a superficial, stereotypical knowledge of Black lives?

LT: Recently my daughter interviewed an actress who grew up in Texas, and she avowed that her parents taught her Black people liked being slaves. She said that now she was ashamed, but as a child she believed it. This woman is talking today! Those thoughts are still alive and they run deep in our culture. They are daily reinforced in order to cover up for a horrible crime… but the only way to heal is to uncover it. Germany has admitted to the Holocaust and apologized. America has never done it. A White friend with whom I was having this conversation once said, “What about forgiveness?” But you can’t be forgiven until you say ‘I have done this horrible thing and I am sorry.’ And it hasn’t been done. So I can’t forgive. Does ‘forgive’ mean, ‘It is all right?’ Well, it isn’t.

TO: We said that perhaps you became an artist in response to a very rough childhood. You attributed the hardship uniquely to your family. But wasn’t it due as well, if not more, to racism? For instance, to the absurd ostracism you experienced in school…

LT: In school, in the hospital… Five years old, in Chicago, taking my tonsils out. I was in the ‘Colored’ ward, that itself says it all. I remember how the nurse grabbed me, threw me down on the bed, took two needles and stuck them into my buttocks acting as if she hated me. Then she wheeled me into the operating room. No one spoke to me. They put something around my mouth… I though they were killing me. Five years old!

TO: Now you connect such treatment to your race. Did you, at five?

LT: Oh, yes! And again, I was the lightest thing in the room. A huge ward — all the kids real dark and I… was the lightest thing.

TO: Were you especially mistreated because of that?

LT: I think so. I can’t read minds, but the nurse really seemed to hate me. She didn’t talk to me. She didn’t say hi…

TO: Was she Black?

LT: My dear… All the nurses and doctors were White. All the orderlies were Black.

TO: Why would a White nurse treat a lighter Black girl worse than a darker one?

LT: Because that was an indication of miscegenation, which usually regards a White man and a Black woman.

TO: So the taboo-about/blame-against/fear-of miscegenation is so deep that a White nurse irresistibly resents a lighter Black child because that means a White man has had an affair with a Black woman? It is horrible.

LT: Did you see the movie The Help? I also read the book. Both are kind of offensive. They are supposed to be about Black women employed in the house by White women, in the South. Truly, movie and book revolve around the White journalist who is writing a piece on this subject. The star, the focal point is the White girl as usual. Anyway, the book says that ladies in the South preferred hiring darker girls — the darker the better. Therefore, the daughter of one of the Black maids isn’t allowed in the house because she is almost White. They don’t want her around, that’s all. In the movie, this point is totally ignored. They made the daughter dark! Well, this changes everything, doesn’t it? And it happens all the time! The story is modified in order to be more comfortable for White people to watch. This is damaging. We can’t always cater to the comfort of White people. This just feeds the delusion, the illusion, the myth…

TO: Why did Southern White women hire the darkest maids?

LT: The darkest the best. It’s a statement. White is superior; Black is inferior.

TO: Do you mean that they wanted to make the difference as clear as possible?

LT: Yes. Then, as we said, the problem was miscegenation. They didn’t want to hire a light-skinned woman because she might have had a White father.

TO: Your art represents Black people within various narrative settings, halfway between daily life and dream. But in some paintings—for example “My Harlem Romance”, or “Yellow Chair” — faces are painted in all kind of vivid hues — ocher, lemon, green, copper — while features and expressions suggest masks. In the small painting titled “Sister of No Mercy”, the white nuns and white students — as opposed to the few black ones — seem to wear masks, as well. Do they? Why?

LT: In “My Harlem Romance” I was consciously emphasizing the variety and depth of skin tones, as an antidote to a feeling/belief shared by many White people — that all Black people look alike and have a flat, dull skin tone lacking in vitality. This idea stems from the consistent effort to minimize the humanity of Black people — the effort to justify enslaving, lynching, incarcerating and marginalizing in a multitude of ways. The ‘masks’ on the faces of the characters in “Yellow Chair” emerged unintentionally — a subconscious revelation of the fact that Black people adopt a pose/attitude to appease White people. This began with the enslavement, of course. Since then, Black people were forced to smile and tap dance for White people as if they were happy to be captive. Forced to avoid eye contact. Forced to act as if they were slow and stupid. Playing the part to appease the Man. As for “The Sisters of No Mercy”… the Catholic nuns by whom I was schooled wore full-body masks. They controlled the narrative. They constructed the lives of the ‘Colored’ children in their care to suit their narrow views. They existed within their self-constructed prisons of bigotry, loathing, and denial.

* For more information on Linda Ternoir, see: https://www.ternoirart.com/

About the author:

Toti O’brien is the Italian Accordionist with the Irish Last Name. She was born in Rome then moved to Los Angeles, where she makes a living as a self-employed artist, performing musician and professional dancer. Her work has most recently appeared in Gyroscope, Pebble Poetry, Independent Noise, Lotus-eaters. Her review in Ragazine.cc of Dimitri Lyacos’ Poena Damni appears here: https://www.ragazine.cc/2019/05/poena-damni-poetry-review/

Recent Comments