A Prague Spring, Before and After (Poetry)

by Michael Salcman

Evening Street Press, 201

$25.00, 106 pages

ISBN: 978-1-937347-33-8

A Prague Spring, Before and After

Reviewed by Charles Rammelkamp

As William Faulkner wrote in Requiem for a Nun, the past is never dead. “It’s not even past.” In his new Sinclair Poetry Prize-winning collection, Michael Salcman demonstrates this in spades. His family, the city of Prague, the entire world are continually haunted by events that to an outsider might appear as dusty data in a forgotten History book but which live in his imagination more closely than the vein in his throat. Born in postwar Prague and raised in Brooklyn, Salcman has never escaped the shadow of the Holocaust in which so many of his Jewish family perished. Nor has Prague escaped the brutality and oppression that have characterized its thousand-year existence.

Indeed, the elasticity of time – “the slippery eel of history,” as Salcman calls it in his “Prologue” – is a major theme of A Prague Spring, Before and After. From the image of the backwards-running clock on the Jewish town hall tower to Einstein lecturing on bent time in Prague, the supple, pliant nature of time recurs again and again in this collection. This is captured nowhere so poignantly as in the poem titled “In the Present Future Tense,” a poem about his uncle in a hospital on Long Island, the blue numbers “on the instep of his arm” all the reminder anybody needs about the presence of the past. In the poem, the uncle confuses three generations of Salcmans “in his brain’s blender / starved for electricity.” And as Salcman tells us in his essay on Prague that concludes this book, “Czechs have no desire to be vaccinated against the past.”

The narrative structure of A Prague Spring is, in fact, all about return – to the past, to Prague. The fifth sonnet in his “Prague Suite” concludes with the line:

a man discovering himself in late middle age.

This discovery is the apotheosis of this collection. The book consists of five parts, beginning in Prague and, like a scorpion biting its tail, ending in Prague. The opening section is called Spring, 1944, ten poems, most of them fourteen-liners which tell the heart-wrenching story of his family, focusing mostly on his father, during the Holocaust. The final poem in the sequence – “(Alfred)” – contains the observation that his father

never explained why the world has no pity for the living

Two of the poems in the Spring, 1944 section contain the lines that are also the book’s epigraph and which Salcman attributes to his cousin Arnold on the occasion of his 80th birthday:

When you knock on the door of strangers,

there are three possibilities: they will send you away,

they will take you in, they will report you.

Part II, Before America, includes some elegies for various victims, including Walter Benjamin and Max Jacob, and a stunning, five-page poetic overview of the Holocaust titled “1942, An Almanac,” a poem addressed to his cousin that concludes with the lines:

But know, no truth is a proof as strong

as the lies of poetry; your memory of that year is mine.

I bring you looted treasure: History’s twisted snakes.

Surely this is one of the true values and purposes of poetry: truth. Capital T Truth. Elsewhere, too, Salcman calls this book an “exorcism.” So be it.

In “Who Will Read This?” from the same section, Salcman writes:

Rub a finger across the furniture

of the world and that thin layer of dust you feel is hatred

of the Jews, the blood libel of the Vatican,

the gospel of the Baptist pulpit, the song of the minaret.

Part III, After, is devoted principally to Salcman’s youth in Brooklyn, and the echoes of the Holocaust reverberate throughout. As well as “In the Future Present Tense,” this section includes an elegy for Simon Wisenthal, “Everything but the Ashes,” and the moving poem, “Explaining the Wound,” about the tragedy and trauma that inform the poet’s verse, picking up on the old Hemingway saw (and developed by Malcolm Cowley) that writers are all “wounded.”

Then in Part IV, Spring, 2007, Salcman returns to the country of his birth, the city that haunts his dreams. For years, before the collapse of the Soviet Union and the “Velvet Revolution” that brought the poet Vaclev Havel to power, Salcman had not dared return for the very real fear that he would be taken captive. He finally makes the return at the age of sixty – and the same old ghosts are still there.

This section also contains the “Prague Suite,” a series of eight sonnets on Prague – its ghosts, its wounds, the Charles Bridge, the clock that runs backwards, and the Golem among them.

Part V, Spring, 1968, contains the lengthy essay, “How I Missed the Prague Spring, a Sort of Memoir,” an exposition on Prague, its history and its challenges. The “Prague Spring” in the book title refers to the 1968 uprising in the same year of turmoil worldwide, when Alexander Dubcek, first secretary of the Czech Communist Party, briefly liberated Czechoslovakia, before the Soviet Union came down on it like a ton of bricks. The term was as hopeful and idealistic as “Arab Spring” would be a couple of generations later.

While presenting an objective, poetic view of the country of his birth, A Prague Spring certainly is an exorcism of demons and a recovery of loved ones, not the least his cousin Magda, who in her life met Josef Mengele, the Angel of Death himself, at Auschwitz. In a closing poem, “First Love,” Salcman remembers her with an aching, tender love. But this is not a true exorcism, for Salcman, like all Czechs, has “no desire to be vaccinated against the past.”

About the reviewer:

Charles Rammelkamp is Prose Editor for BrickHouse Books in Baltimore, where he lives, and edits The Potomac, an online literary journal – http://thepotomacjournal.com . His latest book is a collection of poems called Mata Hari: Eye of the Day (Apprentice House, Loyola University), and another poetry collection, American Zeitgeist, is forthcoming from Apprentice House later this year.

Finding the Raven (novel)

by Patty Dickson Pieczka

$12.00, 283 pages, paper (ISBN #9781530797974)

White Stag (An imprint of Ravenswood Publishing)

Autryville, NC 28318

Finding the Raven

Reviewed by Marta Tandori

Finding the Raven by Patty Dickson Pieczka is an intriguing tale of love, mystery and the paranormal. Somewhat reminiscent of the 1944 Judy Garland musical, Meet Me in St. Louis, in that both the movie and the book are set against the backdrop of the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair, Pieczka’s book, however, depicts a much more realistic impression of life back then than the picture postcard Currier and Ives version presented by Hollywood some forty years after the fact.

Young Julia Dulac is excited about the changes she and her father are about to embark on after her father’s final performance in Pirates of Penzance at the Garrick Theater in St. Louis. Her father had recently purchased a house in St. Louis for the sole purpose of providing some stability for her, but during his final performance, tragedy strikes when something falls from the theater’s rafters, killing him instantly. Julia is told by her father’s attorney that her father had been riddled with debt and their new home would have to be sold to pay off debtors. Suddenly, she has not only lost her father, but she’s homeless and penniless as well. In a state of shock, Julia finds affordable lodging at Mrs. McKinney’s Boarding House for Ladies and, shortly thereafter, finds work in a sweatshop factory making shirt collars. In St. Paul, Minnesota, Rose Hillman, well-heeled heiress to the Hillman Cereal fortune, is over the moon because she’s in love and she’s pregnant. The only problem is that her suitor, Eric Swensen, is a bank teller and would hardly be considered appropriate husband material by her father. Her father immediately banishes her to St. Louis for a year at the same boarding house where Julia is living before Rose can tell Eric where she’s going.

A devastated Rose and Julia quickly become fast friends despite Rose’s shocking condition. Rose decides she must find a husband who will take on her and the baby. She answers an advertisement in the paper and, after an uncomfortable courtship, she marries the utterly undesirable Herman Tidwell, a repulsive man claiming to be a partner in the same law firm that had represented Julia’s father. Meanwhile, an exhausted Julia is fired from her factory job after thwarting the unwanted advances of the floor manager. With her future looking utterly bleak again, she angrily throws her lucky pink Buddha against the wall, shattering it to pieces. To her surprise, hidden inside is a black crystal that she goes to have appraised at the local jewelry store where she meets a young man called Monroe Michaels, who tells her he’d like to introduce her to a fortune teller at the World’s Fair. The fortune teller, Clarice, tells Julia that the crystal is called the Raven and that it has the power to give her sight. Once Julia looks into the crystal, she begins to see things; things that will change the course of hers and Rose’s lives forever.

In addition to weaving an engrossing story in Finding the Raven, Pieczka’s two main protagonists happen to be young women with substance. At a time when well-heeled women were considered to be little more than ornaments for a man’s arm with few rights outside of child-rearing and the running of the household, the characters of Julia and Rose evolve from being helpless females to slowly standing on their own two feet as they take command of their lives. There is a wonderful cast of supporting characters – from Mrs. Kinney, owner of the boarding house, to Mr. Fletcher, the owner of the jewelry store that Julia eventually purchases, and finally, the men in both women’s lives. In order for a book to be compelling, it must depict humanity in the truest sense and this story has it in spades. It depicts life at its most basic and needy, to its most spoiled and pampered.

Pieczka has a wonderful gift for bringing a setting to life and painting it with hues of vibrant color so real that it unfolds before our eyes. In addition to paying tribute to the social morés of the day, Finding the Raven also pays homage to the technological and industrial advancements that made America so exciting at the time with the creation of electricity, the telephone, the motorcar and even waffle cones. Overall, Finding the Raven is akin to having taken a wonderful journey back in time – one definitely worth taking!

About the reviewer:

Marta Tandori’s first work of juvenile fiction, BEING SAM, NO MATTER WHAT was published in 2005, followed by EVERY WHICH WAY BUT KUKU! in 2006. With her more recent endeavors, Marta has shifted her writing focus to “women’s suspense”, a genre she fondly describes as having “strong female protagonists with closets full of nasty skeletons and the odd murder or two to complicate their already complicated lives.”

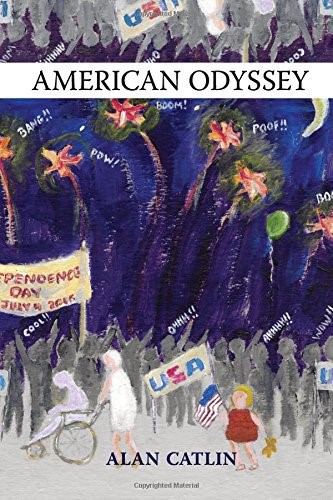

American Odyssey (Poetry)

by Alan Catlin

FutureCycle Press, 2016

$14.95, 74 pages

ISBN: 978-1938853968

American Odyssey

Reviewed by Charles Rammelkamp

It might be misleading to describe Alan Catlin’s powerful new collection of poems as ekphrastic, since the term conjures a vision of paintings, sculpture, fine art, and so many of these poems are inspired by the work of photographers, including photojournalists, whose work is more about social critique than aesthetics. American Odyssey is a journey through the nightmare aspects of the American Dream.

The title comes from a poem in a series of poems which open the collection, poems that are inspired by Mary Ellen Mark, the photojournalist whose work includes Ward 81, photographs of female “patients” in the maximum security section of Oregon State Hospital, and Streetwise, teenagers in Seattle living on the streets.

Just as Gene McCormick’s cover art depicts a wholesome Independence Day parade heaped with understated cynicism, “Mary Ellen Mark’s American Odyssey” conflates onlookers at a Memorial Day parade with a cavalcade of the American freaks Mark photographed:

the shelter kids, Halloween-costumed orphans

left behind on streets without dreams on city corners

in wicker baskets or in dumpsters like so much garbage

people close their eyes to in order not to see;

families in cars, in twenty-dollar motels for a night,

all six of them and the pets, filthy clothes washed

in sinks hung out to dry on shower stall rungs and

towel racks, six hours in occupancy and the room

is as totaled as the car left at the side of some

unnumbered road, already rusted and ravaged, seeming

as if it somehow had always been there; preteens

in wading pools sharing a smoke or dressed like ten-

dollar whores by the boardwalk; adolescent beauty queen

contestants, the winners and the losers, full immersion

river Baptists, be-robed elevated train prophets and

their handlers working aisles, donations on demand;

survivalist family training camps, children with guns….

After the half dozen or so Mark poems comes a series inspired by Robert Mapplethorpe’s photos of androgynous females – Laurie Anderson, Eileen Myles, Patti Smith – and others of his that likewise blend the contradictory, such as “Mapplethorpe’s Hand and Flower (1)”:

The image is all about simplicity:

a contradiction in terms,

two objects in opposition,

carefully arranged and juxtaposed:

a hothouse orchid and a man’s

clenched fist, anxiety and grief;

the longer they are observed,

the more similar they become.

We can already see where Catlin is going with this, as if letting us in on a joke (American Joke might be an alternate title for this collection). The next series of poems, which takes off from the work of the illustrator/caricaturist Ralph Steadman, confirms this impression – Steadman’s Freud, Steadman’s Macbeth, Steadman’s Milosevic and my favorite, “Ralph Steadman’s The Brain of Dr. Hunter s. Thompson According to Gray’s Anatomy,” which seems to take off from Steadman’s famous cover illustration for Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, but could refer to any number of Thompson illustrations. Thompson, too, famously savaged the American Experience in his gonzo journalism.

Through several more brilliant sequences – “Dream Dates” with various suicides and otherwise troubled female artists – Plath, Sexton, Woolf, Diane Arbus and Billie Holiday among them; “Our Lady” poems involving dubious saints (of Kitchen Appliances, Contraptions, and Trenches, among them), and a series inspired by the Vietnamese-born poet Quan Barry – Catlin expands the freakish universe beyond American shores.

Movingly, the the collection comes to an end with a ten-poem sequence inspired by the REQUIEM exhibit of photography by photographers who died in Vietnam and Indochina. Of course, these are pretty bleak scenes of war, perhaps the most heartbreaking of which are the ones about uprooted Vietnamese families caught in the crossfire. Think of the Syrian refugees today. “Young Girl with Two Kittens, a Chicken and Her Father’s Rifle, Vietnam, 1974” shows a picture of a family preparing to flee, hastily packing their belongings into boxes.

The rifle the child is guarding

should be an incongruous element in

this arrangement, but this is so clearly

a war zone where the only hope is

escape, that it is all the details of domestic

life that are out of place, unnecessary,

soon to be of no use.

Again, the juxtaposition of opposing elements, the normalizing of the horrific.

Alan Catlin’s poetry is often grim, focusing on people who have gone off the rails either deliberately, stupidly, or from substance abuse or lack of self-control, or just plain having the deck stacked against them. American Odyssey fits this theme but elevates the pain to a level of the zeitgeist, as if all this suffering is not simply tragedy foretold but the unflinching observation that this is how the world works, always has, always will, no matter how we candy-coat or pretend it’s the anomaly.

About the reviewer:

Charles Rammelkamp is Prose Editor for BrickHouse Books in Baltimore, where he lives, and edits The Potomac, an online literary journal – http://thepotomacjournal.com . His latest book is a collection of poems called Mata Hari: Eye of the Day (Apprentice House, Loyola University), and another poetry collection, American Zeitgeist, is forthcoming from Apprentice House later this year.

Café Select

Poets’ Choice Publishing, 2016.

124 pages

by W. M. Rivera

Mizzling and Honking: A review of Café Select,

poems by W. M. Rivera, with art by Miguel Conde

Reviewed by Clarinda Harriss

Proud as I am of having been the publisher of W. M. Rivera’s first full-length poetry collection, Buried in the Mind’s Backyard,” I am almost happy that my press, BrickHouse Books, Inc., is not the publisher of his latest, Café Select. Being just a reader allows me to say with an unprejudiced voice that the new Rivera book is so absolutely stunning it threatens to blow the others out of the water. With a strong under-growl of envy I shout “Kudos!” to Poets’ Choice Publishing for bringing out this visually and viscerally electrifying book.

In Café Select, Rivera’s poems are separated into sections by three “galleries”–paintings, watercolors, and drawings–from American-born Mexican artist Miguel Condé. Friends since the 1950s, each the son of a Mexican father and an American mother, each an art lover, these artists’ images delight, amuse, dazzle, daze, haunt. Condé’s visual pieces (20 in all in full color; what a wealth!) combine mystery (Who are those red-haired men in their wild costumes and marvelous hats? Are the two “doctors” in their highly unusual garb executioners or seekers after the brain’s secrets?) Try to imagine cheerful Bacons or Bosches. That’s how Condé’s pictures tease and mystify.

Rivera, like Conde, suggests that relationships, especially male-female relationships, excite us by asking riddles that have no lasting answers. Though all his poetry collections are fueled by fleshly heat, Café Select suggests that out of the flesh arises (or descends) Desire, capital D, Desire in the archetypal sense. In “Passing Fancies,” under an epigraph from Ovid—“My desire has ambitions on them all”— Rivera writes of “delighting in places I’ve never been. . .their catwalk spikes,/ their printed pantyhose” and concludes, “I’ve ambitions on them all./ Tantalus must be my brother.” Note that word “women” does not appear.

Yet Rivera can also be humbly and tenderly personal in his “ambitions.” He ends one of the finest poems in the collection thus: “It’s a perfect day/ today, the kind of day I’ve been waiting for,// knowing you, not knowing you, only/knowing you’re coming, if just for coffee.”

Whereas Condé’s visual images seem to come from no known time or place—another universe, rich and marvelous—Rivera’s poems are rich in people and places from a world we readers live in. But Rivera’s poems are varied, vigorous, and often surprising. They are rooted in the quotidian but not the mundane. Rivera makes good use of the poet’s toolbox: language that engages both with sound and sense. He risks mixing levels of diction and allusion, ranging from the Greek and Roman classics to pop culture, even deliberate cliché. In one of his most intellectually interesting poems, “The Magic Trickster,” he states that

The black holes in the universe confirm

the reality of becoming nothing. . .

and ends by asking

How conceptualize our galaxy. . .

our evolution, the nature of things learned . . .

dragged into a black hole, zapped! The ‘magic trickster’

nowhere to be seen? Nor hide nor hair of us!

And in a poem about a rainy traffic jam, drivers feel the “mizzling wet” (spellcheck has never heard of “mizzling”!) and put “honks on hold” within two short lines. They make a joyful noise.

Though all of Rivera’s poetry collections throb with sex, either overtly or as an undercurrent, in Café Select sex and sexuality are approached even more directly here than in the previous books. Rivera proves that, as he and his writing age, they do so more in the manner of Yeats (think of the marvelous late-Yeats Crazy Jane series!) than of say, Wordsworth whom many critics believe did his best work early (and to whom I’m indebted for the quotation below).

There’s red blood in the lustiness of both Rivera’s and Condé’s imagination; if we’ve been lucky, we’ve felt it ourselves and can perhaps, along with these two artists, recollect it “in tranquility. . . till the tranquility disappears.”

About the reviewer:

Clarinda Harriss is the longtime editor and director of BrickHouse Books, Inc. Her most recent books are MORTMAIN, DIRTY BLUE VOICE, THE WHITE RAIL, and HOT SONNETS; AN ANTHOLOGY (co-edited with Moira Egan).

Memorials

by Mieczyslaw Jastrun

Translated by Jeff Friedman and Dzvinia Orlowsky

ISBN-13: 978-1935084600

106 pages, paper, $16.00

Diálogos Books

http://www.lavenderink.org/content/diag

Memorials

Review by Miriam O’Neal

Mieczysław Jastrun’s, Memorials, translated by Dzvinia Orlowsky and Jeff Friedman is a strange, meditative collection. As the translators explain in their notes, ‘First efforts [at translating] brought us into a world perceived through a dream-like, elusive consciousness—fragmentary, and intense, evocative and stimulating—one that could not bear very much reality.” And yet, in the final product we discover a reality so specifically of the physical world, it metamorphosizes Jastrun’s fragments into a discoverable whole.

The poems are full of physical symbols and leitmotifs that create a primal and personal mythology. There are stars and fires, doorways and trees. There is darkness and salt and snow and iron. Jastrun turns our gaze to meet the natural world with an admonition to be ware of our human selves. Each reading of these poems seems to deepen his invocation of the opposite of anthropomorphism, which is chremomorphism, the attribution of non-human traits to human beings. Perhaps the most significant of these attempts occurs in the poem “Eyes”, in which the speaker, presumably the eyes themselves, begins by explaining that “God created me once—/ isn’t that enough?/ Do I need to be re-created/ by myself and then, / by others?”

This first set of questions reminds the reader that, in fact, as ‘creations’ we are doubly so, because of our human proclivity for inventing and/or recreating ourselves. Animals do not recreate themselves, they go about the business of living their lives.

Later in the poem the speaker asks,

If we think in categories,

can we ever fully comprehend

mist, Arctic lichen, hoary

young planets?

and then explains that

We can anthropomorphize a reed,

but Pascal’s mind, already alive

in nature, was a delicate wine

flowing from the branches.

The speakers in Jastrun’s poems are often converted into the objects they have used as metaphors. Corn is asked questions, an empty glass is thirsty, etc. The “I” becomes a tree, a star, a stone, a bird, wild grapes. In the poem “Rock Paintings,” the paintings speak for their own images, as if to say ‘What you see here is all that we could provide for those who created us. We are their voices, we are their belief.” Organized into three, brief three line stanzas, it addresses the limits of the made to actually create change.

I couldn’t change

these stones into bread—

I wasn’t that strong

I couldn’t tear apart

these words—

the future removed me—

only to try again

This was not anesthesia

but pain—faith.

The idea of faith as pain and pain as faith surges through the collection as does the sense of creator in the created. The objects of the poems speak for themselves as well as for the abstractions the poet sees anchored in the material world as in the poem “Wall”.

I wanted to sleep peacefully

but my conscience flung me

awake. I shot the belly

from a man on the Cross

I wanted to flee to the window

turn away from light

This is what God did

To keep the wall alive

This wall, this air—

after the show, emptiness

stood there, yet far

lips—wall

We can only guess at the source of his crisis of conscience, not knowing if it is the stuff of a dream, a memory, or his having survived the war, but we can feel the way the ‘emptiness/ [stands] there….’ filling up the space around the awakened speaker. He give us the experience of palpable emptiness.

Jastrun’s own faith is the catapult for and the lurking catamount in these poems. Born into a Jewish family, he converted to Christianity as a teenager, prior to the Second World War and the poems of Memorials often visit the irony that, while it might be said his conversion saved him twice over, it left him with a survivor’s guilt that was doubled as well. His poems often seem to speak for those who cannot, though, at the same time the words often go unheard, as in “Rock Paintings,” and later, in “Small Grief” where the speaker tells us “I find deaf words,/ carved stone…// In vain I pray for rejuvenation’/ God, god, too many gods….”. The words themselves cannot hear what they are saying; the gods cannot hear what the words have to say; only the speaker hears them, and that is apparently not enough.

Though several biographers have stated that Jastrun purposely avoided any ‘Jewish themes’, it would be difficult to argue against the presence of the shadow of the Holocaust in these poems. From time to time, the poems in Memorials paint in specific acts and artifacts of the war, as in “Civilization”. We are shown, with broad brush strokes, the combined rise of the Third Reich and the fall of the Jewish diaspora: “Troops swell as welders work on the rail,” while the Jewish community, walled in, in various ghettoes across Eastern Europe, tries to survive and “…only one/ female artist exhibits her work/ displays what she sees.” The artist Jastrun refers to seems to be Esther Lurie. Lurie, whose family had migrated to Palestine after World War I, had been visiting relatives in Latvia and Lithuania when the Germans closed off Kovno, where she was staying with her sister. Commissioned by the Council of Elders in the Kovno Ghetto, to record the community’s experiences, Lurie and her much of her work survived both the ghetto and later, the Stutthof concentration camp in Germany. There is also “Saskia” of the red carnation, and Thomas Waldmann, who taught listeners how to “…hear the silence after the music.” The poet also makes a single reference to ‘4 folded pages’, which seems to refer to the Haggadah, the prayer book used at the Seder Supper each Passover, an artifact of the life he would have lived prior to his youthful conversion. Such objects and people inhabit these poems as concretely as a single gunshot to the head, or the bullfinch bird in the forest at Katyn.

There are also poems that show us how the patterns of our collective behavior, bring us again and again to the same outcome. In “No Place”, the speaker tells us

This man says yes,

fear in the air

of those who enclose him

…..

….

His friends turn him in

without hesitation

giving the executioner

all the evidence he needs.

No longer threatened,

the family leaves the palm

of the valley and assumes its place

on the hill with three birches.

The poem’s title tells us that this is not a poem about a particular place. Rather, it presents a pattern of human behavior that brings us again and again to the same place. As a survivor of the Nazi occupation of Poland who lived outside of the Jewish experience, but with the knowledge of his own precarious status, Jastrun writes as witness and about what he was haunted by.

The poems in Memorials are riven with the light that comes from reflection. Mirrors, water, windows, all shine with sunlight. However, the light source referred to most often in the collection is stars, a light that is only visible in the presence of darkness. From time to time we hear the echo of Eliot’s “Burnt Norton,” section II, which begins in mud and ends in stars; Rilke’s, “Evening,” which ends with “stone in you/ and stars.”; and the final scene in Dante’s Inferno, in which he climbs up and up and up, returning from the world below, and his first view is the starry sky. In these poems. Jastrun has upended the ‘light’ motif . He becomes the dark in order to show us the mystery of light; what is visible only by way of darkness.

Comparing the Polish text in this bilingual edition, to its English counterparts, we can see that in some poems, the lines of the originals run much longer or, as in “Memorized in Childhood”, the stanzas are shaped differently. Some of the former can be attributed to the normal happenstance of translation where the corresponding English word is shorter and/or less likely to be a compound, etc. However Orlowsky and Friedman tell us in their notes, that they also made the decision to reduce some of the “dense layers of language [of the originals] to get at the core of [Jastrun’s] vision.” Their choices have shaped this English language version of Memorials into a wersja or version of Jastrun’s own voice. It is a voice we hear with both confidence and a discomfiting wonder.

About the reviewer:

Miriam O’Neal has published poems and/or reviews in AGNI, Marlboro Review, Louisiana Literature, Birmingham Review, The Guidebook, previously in Ragazine.CC, and elsewhere. Her translation of Italian poet, Alda Merini earned her a Beginning Translator’s Fellowship from the American Literary Translators Association (ALTA) in 2007. Her manuscript, We Start With What We’re Given is currently looking for a home.

Miriam O’Neal has published poems and/or reviews in AGNI, Marlboro Review, Louisiana Literature, Birmingham Review, The Guidebook, previously in Ragazine.CC, and elsewhere. Her translation of Italian poet, Alda Merini earned her a Beginning Translator’s Fellowship from the American Literary Translators Association (ALTA) in 2007. Her manuscript, We Start With What We’re Given is currently looking for a home.

Recent Comments